Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: The Flight from Reality

Aug 8, 2019 | Paul Monk

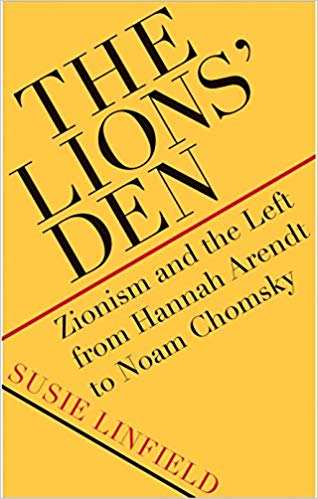

The Lions’ Den: Zionism and the Left from Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky

The Lions’ Den: Zionism and the Left from Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky

Susie Linfield, Yale University Press, 2019, 400 pp., $59.99

Before stumbling upon this book I’d never heard of Susie Linfield. Having read it word by word, I now have enormous respect for her.

In a field littered with anti-personnel mines, fenced off by ideological barbed wire and raked with partisan machine-gun fire from entrenched positions, she has done the seemingly impossible. She has crossed no-man’s-land and shown all of us the flag of critical and humane reason from the other side. This is a breathtaking scholarly achievement.

It need hardly be said that the feral intellectual and brutal physical struggles over Zionism and the existence of Israel are hardly likely to be brought to an end by her labours. But if any kind of intelligent and constructive solution to the matter is to be generated, her kind of thinking and scrupulous attention to detail and inference will most definitely be required.

The mention of Hannah Arendt and Noam Chomsky in her title was well-conceived. Both names are so well-known and – by different readerships for very different reasons – so widely admired. When one opens her book, however, it is to find that these are the bookends: the first and last of the figures she cross-examines. In between, we find Arthur Koestler, Maxime Rodinson, Isaac Deutscher, Albert Memmi, Fred Halliday and I. F. Stone.

With the exception of Memmi, with whose life and work I was previously unacquainted, I have long been familiar with all these figures and read a good deal of their work. Yet she showed me things in every case that had eluded me over many decades. Moreover, she did it with a nuanced attention and human empathy that again and again almost took my breath away.

Without exception, she exhibits an intimate acquaintance with the social and family background, life experience, writings and critical reception of these eight figures. That alone is a formidable accomplishment. But to then steer her readers through the labyrinthine world of modern Jewish thought, Jewish anti-Zionism, competing strands of Zionism, antisemitism, Arab politics and the evolution of the global Left, and enable us to come out both enlightened and liberated, is an altogether exceptional achievement.

In some ways, this is all the more astonishing because Linfield is not, by education or prior scholarly training, an academic specialist on any of these things. Her early training was as a ballet dancer at George Balanchine’s School of American Ballet in New York. She danced as a student in productions of Don Quixote and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, then in the Royal Ballet’s New York production of The Nutcracker, directed by none other than Rudolf Nureyev.

Opting out of a career in ballet, she studied at New York’s Ethical Culture Fieldston School from the age of 15; then earned a bachelor’s degree in American history at Oberlin College. After moving to Boston, she ran the feminist newspaper Wages for Housework.

Her next move was back to New York, where she studied journalism and documentary filmmaking at New York University. She has been a professor in the journalism department there since 1995. She has served as Editor-in-Chief of American Film, Deputy Editor of The Village Voice and Arts Editor of The Washington Post.

Perhaps it is her extensive experience as an editor that has enabled her to parse the works of so many writers with a discerning eye. But it is one thing to be critically discerning with regard to a particular author or article or kind of writing; it is quite another to exhibit a consistently high standard of engagement and discernment across a subject one has not previously studied which is so cluttered with bitter and polemical argument, as well as deeply rooted historical, religious and ideological differences of opinion – and, for that matter, personal feuds. Linfield has done this to a very high degree.

Her critique of Hannah Arendt’s attitudes towards, and writings on, Israel and Zionism is brilliant and eviscerating. I confess I have been a great admirer of Arendt for decades and have all her books and more than a few about her. Yet I learned things and saw things about her work in Linfield’s pages which I had not previously allowed myself to see or understand. Two of these things stand out: her serious lack of consistency or realism with regard to the formation of the state of Israel and her racist attitude towards Sephardic and Mizrahi [Middle Eastern] Jews. It’s quite astonishing to read her as Linfield does and register her disdain for not only their poverty and lack of European education and culture, but their physical appearance and manner of speech.

Arthur Koestler was no better. Maxime Rodinson only marginally so. What Linfield illuminates in her critical assessments of these three, especially, is that they were all deeply ambivalent about their Jewish identity and the whole Zionist project – Koestler and Rodinson to the point that they wanted to see Judaism and any distinct Jewish people disappear. This led to ambiguous and unstable attitudes towards Zionism and the formation of Israel as a normal nation-state.

What they had in common with the others in this regard is a confused idea that the Jewish Diaspora had somehow been a “mission” for the Jewish people, staking out the claims of universal values and transcendent humanism. It hadn’t been, of course. It had been forced upon the Jewish people by the Roman emperors (Vespasian/Titus and later Hadrian) long ago, then reinforced by endless expulsions and pogroms in the Christian and Muslim worlds ever since.

But the driving idea in Linfield’s book is not simply a critical reflection on the individual attitudes of eight widely-read thinkers. It is the question: how did the global Left shift, in the years after the creation of the state of Israel, from being committed to universal human rights and democratic emancipation to being champions of Arab dictatorships and terrorist organisations against the very existence of Israel?

The key is a Stalinoid hostility towards “imperialism”, in which Israel became a proxy for the latter. But it didn’t help that so many Jewish intellectuals were anti-Zionist or antisemitic or delusional about Middle East realities.

In no case is her critique of their confused thinking more scathing than in that of Noam Chomsky. Her cutting remarks, ironic asides and expressions of puzzlement in the cases of Arendt, Koestler, Rodinson, Deutscher, and Stone, and her comparative praise for the thoughtfulness (despite various errors of judgement) of Halliday and the wisdom of Memmi, are all wonderfully well-wrought. But her cross-examination of Chomsky is absolutely devastating. He and his many partisans are likely to dismiss it on what one might pre-emptively dub ad feminam grounds, or simply ignore it altogether, but it warrants very wide circulation. She buries Chomsky – ceremonially and definitively.

The chapter runs to 36 pages and merits being read closely and in full. She opens with a wry reference to the 2016 film Captain Fantastic, in which a left-wing, off-the-grid family celebrates Noam Chomsky’s birthday each year and sings heartfelt odes to “Uncle Noam”. She then sets up her critique with the following observations:

Perhaps because of his work in linguistics, Chomsky is regarded as an expert on virtually any topic he addresses. There is an irony in this, since his best-known political essay, ‘The Responsibility of Intellectuals’, was an attack on the very concept of the expert. Nonetheless, his knowledge of the Arab-Israeli conflict is viewed as deep and wide… The most surprising – no shocking – thing one learns when immersing oneself in Chomsky’s Middle East writings is how inaccurate these descriptions are… The other surprise is the degree to which Chomsky… is guided by wishful thinking.

She concludes that it is the very “simplicity of Chomsky’s worldview” that “is the source of its power and popularity.”

She shows that, since 1976, Chomsky has tirelessly insisted that Israel and the United States have rejected every possibility for peace in the Middle East, while the Arab states, the Palestinian leadership and Iran have again and again held out the olive branch only to be spurned. He rests this argument, she states, “almost completely – dare I say religiously? – on a little-known and never passed United Nations resolution of January 23, 1976.” Since then, he has cited – more precisely, mis-quoted it – dozens of times in his writings.

She excoriates his writing, on point after point, climaxing, on pages 286-87, in a fusillade of refutations of his key claims in 14 specific cases, beginning in each case with the categorical statement, “It is not true.” She concludes with the observation that, whatever the errors of the others in her book, with Chomsky “the flight from reality reaches its apotheosis.”

That Chomsky is, nonetheless, so widely lionised is a scandal. If you are scandalised by it, read Linfield and be edified.

Paul Monk (www.paulmonk.com.au) is the author of 10 books, of which the most recent are The Secret Gospel According to Mark (2017) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018), both of which are available through major on-line retailers. © Paul Monk, all rights reserved.

Tags: Anti-Zionism, Israel, Media/ Academia