Australia/Israel Review

Elect, Rinse and Repeat

Jun 26, 2019 | Amotz Asa-El

Israeli politics had seen pretty much everything over the past 70 years – broad, narrow, and emergency governments, rotating prime ministers, national leaders indicted, convicted and jailed, newborn parties storming into power and veteran ones collapsing overnight. Yet what happened after this year’s election was novel even for the Jewish state.

A mere six weeks after having been elected, Israel’s 21st Knesset dissolved itself on May 29 by a vote of 74 to 45. The general election that this motion set in train has been set for September 17, a mere six months after the previous election on April 9.

Israel has never before had two general elections in the same year. Every Knesset up until this one has served for more than two years, and most dissolved after serving something close to their full four-year term, thus providing a measure of stability in a system beset by the stormy coalition politics that have produced 34 governments in 71 years.

This year’s unusual turn of events is particularly odd, considering that the April 9 election was by no means inconclusive – the ruling Likud and its conservative and religious satellites won collectively 65 of 120 Knesset seats, a decisive victory by Israeli standards.

Moreover, when Israel did once have a genuinely inconclusive election in 1984, the two large parties of the day, Likud and Labor, ended up forming a unity government that actually proved durable and even saw the Knesset that elected it serve out its full term.

Back then, politicians were driven by a set of emergencies – war in Lebanon and hyperinflation at home – that led them to set aside partisan and personal considerations. The dynamics of 2019 have been entirely different.

The man who triggered the snap election that no one saw coming is former Defence Minister Avigdor Lieberman.

Though his party, Yisrael Beitenu (“Israel Our Home”), only won five seats, that modest following provided him sufficient leverage to force the new election, because without him Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu did not have the minimum 61-vote parliamentary majority that proper governance requires.

Theoretically, Netanyahu had an alternative option, to form a coalition with the main opposition party, Blue and White, which, like the Likud, won 35 seats. Moreover, in terms of its positions on most domestic issues and foreign affairs, there seems little reason Blue and White could not cohabitate with Likud in one coalition.

The only problem is that the new party, headed by Lt-Gen (res.) Benny Gantz, demanded that Netanyahu step aside until the corruption charges he faces have been resolved. Since Likud is not prepared to replace its leader, Blue and White’s stance precluded a broad coalition.

That is why a conservative coalition was the only game in town, a constraint that Lieberman – one of the most experienced, shrewd, and unpredictable politicians in Israel – detected early on and set out to exploit.

The secularist Lieberman’s pretext concerned Netanyahu’s concessions to his ultra-Orthodox allies on conscription for ultra-Orthodox students in religious seminaries.

For decades, ultra-Orthodox men enjoyed deferments from military service as long as they studied and did not join the workforce. The law was later changed, in order to entice more ultra-Orthodox men to work, but the new law was later ruled unconstitutional by Israel’s High Court of Justice.

The Knesset was therefore compelled to pass new legislation, and last July passed the first reading of a bill that set an annual quota of 3,348 ultra-Orthodox conscripts for the IDF, a figure that would be gradually raised over eight years to 5,737. If the quota went unmet, every seminary that failed to deliver its relative share of conscripts would lose an equal portion of state funding from its budget.

The bill passed in a first reading despite the protestations of the ultra-Orthodox parties, and with the support of the liberal-centrist Yesh Atid faction which has since become part of Blue and White.

After the April 9 election, the ultra-Orthodox parties obtained Netanyahu’s agreement that the new bill’s mechanism would not be turned into law, and instead just be passed as a government resolution, leaving it continuously open to re-negotiation.

Lieberman demanded that what had been passed in a first reading be made law through second and third readings. When Netanyahu failed to deliver this, Lieberman said he would not join the coalition.

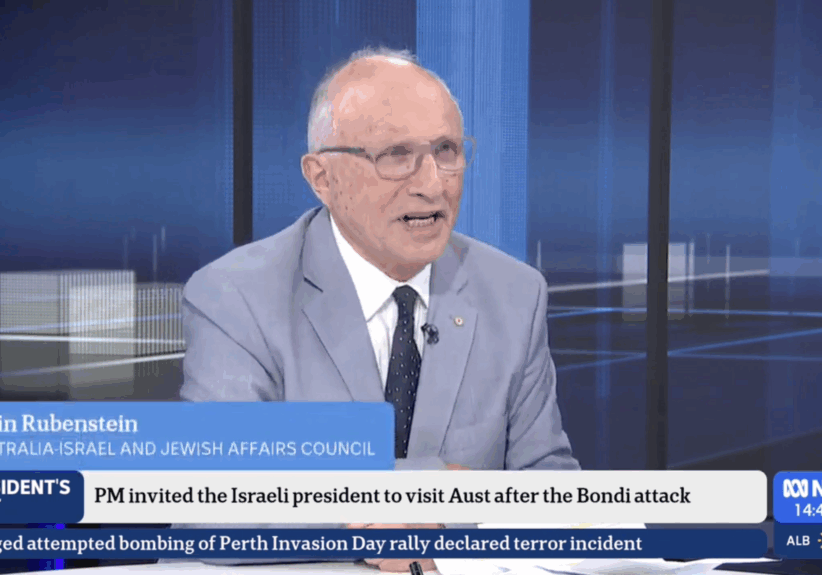

Netanyahu: Caught unprepared by Lieberman’s stance

Netanyahu was caught unprepared. Worse, by then, time was running out for him, as the 42-day period the law gave Netanyahu to establish a government was about to expire.

Concerned that President Reuven Rivlin might pass the mandate to form a government to Blue and White leader Benny Gantz, Netanyahu asked his coalition partners to back him in a call for a new snap election.

Lacking much of a choice, Netanyahu’s partners did as they were asked, even though at least some of them risked losing ground in a new election.

Paradoxically, the opposition – which one might expect to back any motion for an early election – opposed the Government’s bill, arguing that before the Knesset disbands itself so prematurely, Gantz should be given a chance to form a coalition.

The opposition’s hopes were dashed, however, once the two Arab-majority parties, Hadash-Ta’al and Ra’am-Balad, decided to back the government’s bill. The leaders of those parties hope they can now recoup some of their losses from the election on April 9, when their representation shrank by nearly one quarter due to low voter turnout among their constituents.

The Arab politicians were thus the first to use the unfolding drama in order to jockey for better positions in the wake of the back-to-back election. Yet the key question Israeli pundits have all been asking is not about the Arab parties but about what drove Lieberman to take the gamble of his life?

Lieberman’s own take was that he was driven by principle; that he had to speak for the majority that wants ultra-Orthodox men to serve in the IDF like all other Jewish Israelis. Pundits, however, note that in the past Lieberman’s fight for his secularist convictions never resulted in any move quite as drastic as the dissolution of a newly elected legislature.

It follows, according to practically all Israeli analysts, that Lieberman was likely driven less by ideology and principle and more by opportunism, both personal and partisan.

On the personal level, he is apparently sensing Netanyahu’s imminent departure, or at least feels he can hasten his exit from politics. If true, this theory would mean Lieberman’s ultimate aim is to return to Likud, where his political career began, after Netanyahu clears the stage, and hopefully be crowned his successor.

On the partisan level, Lieberman’s move reflects an attempt to change his electoral emphasis, for the third time.

Back when he established it 20 years ago, Lieberman’s Yisrael Beitenu party courted the Russian-speaking electorate and focused on bettering the social lot of a population that had arrived recently from the former Eastern Bloc. A decade on, as that electorate’s children felt less in need of a sectarian party, Lieberman elected to court hawkish Israeli-born voters by fielding candidates like Yair Shamir, a respected industrialist and son of former prime minister Yitzhak Shamir.

However, the hawkish ticket which led to Lieberman’s resignation as defence minister last November ostensibly to protest Israel’s restraint in responding to Hamas attacks from Gaza – thus triggering the election in April – appears to have also spent itself. This time around, it generated only one-third of the 15 seats Lieberman won last decade. Apparently, this is what led him to decide to hoist his other flag, the anti-clerical one, which might lure in some of Blue and White’s secularist electorate.

If he manages to indeed grow his electorate, Lieberman will be able to proceed to his next presumed goal – obtaining the succession to Netanyahu. Such a plan only makes sense if launched from within the Likud, so Lieberman would first have to rejoin.

Whether this plan is viable or not, it is evident that Netanyahu suspects that this is what Lieberman is attempting.

That is why the first thing Netanyahu told a knot of reporters after a second election became inevitable, was that “Lieberman is now part of the Left.” Such phrasing is a potent accusation in Israeli conservative parlance and a clear statement on Netanyahu’s part that he will now treat Lieberman as a strategic threat.

Sources close to Netanyahu told Israeli TV he will triple spending on advertising to Russian-speaking voters in an effort to pull the political rug from under Lieberman’s feet.

It is but one of several rifts today besetting the conservative side of Israeli politics. Another rift looms between Netanyahu and the “New Right” party, which narrowly missed the electoral threshold to gain entry to the Knesset and intends to run again in September. In what struck some as an act of political vengeance, Netanyahu fired the New Right’s two leaders, Naftali Bennett and Ayelet Shaked, who had been stranded in his interim government as ministers of education and justice, respectively.

The two, who seceded from the predominately modern orthodox Bayit Yehudi (“Jewish Home”) party, were also attacked by that party’s Orthodox leaders. All talk of reunification between New Right and Bayit Yehudi thus looks impractical.

Meanwhile, in a move apparently designed to impress the liberal secular electorate that Lieberman is eyeing, Netanyahu appointed Likud MK Amir Ohana as Justice Minister, Israel’s first-ever openly gay cabinet member.

However, the 43-year-old Ohana, a lawyer who lives with a boyfriend with whom he is raising twins, is a conservative who liberals suspect may try to help Netanyahu escape trial on the corruption charges levelled against him through introducing an automatic parliamentary immunity.

Whether or not Netanyahu or Lieberman manage to woo liberal voters, the timeframe of the new election is so short that the general expectation is that the Knesset it will produce will be nearly identical to the short-lived one it will replace.

Of course, there will be some minor changes, like Labor’s yet-to-be-chosen leader, to succeed Avi Gabbay who announced his retirement from politics following his party’s trouncing in the April poll. And yes, the right-wing bloc has a chance to recoup some of the votes it lost due to the failure of Bennett’s New Right to cross the electoral threshold.

Yet these won’t change the big picture, which is that for nearly two decades now more Israelis have been tending to vote for right-leaning parties, and fewer for those on the centre and left.

What might change the picture is Netanyahu’s pre-indictment hearing with Attorney-General Avichai Mandelblit. Scheduled for October 2, it will come a few weeks after the new election, in the week between the Jewish New Year and Day of Atonement, the period known as the Days of Awe when Jews ponder their sins over the past year.

Whether or not Netanyahu sinned will be for him and Mandelblit to discuss. In their pondering, however, they will be joined by almost the entire Jewish state.