Australia/Israel Review

Protests reveal state of the Iranian “revolution”

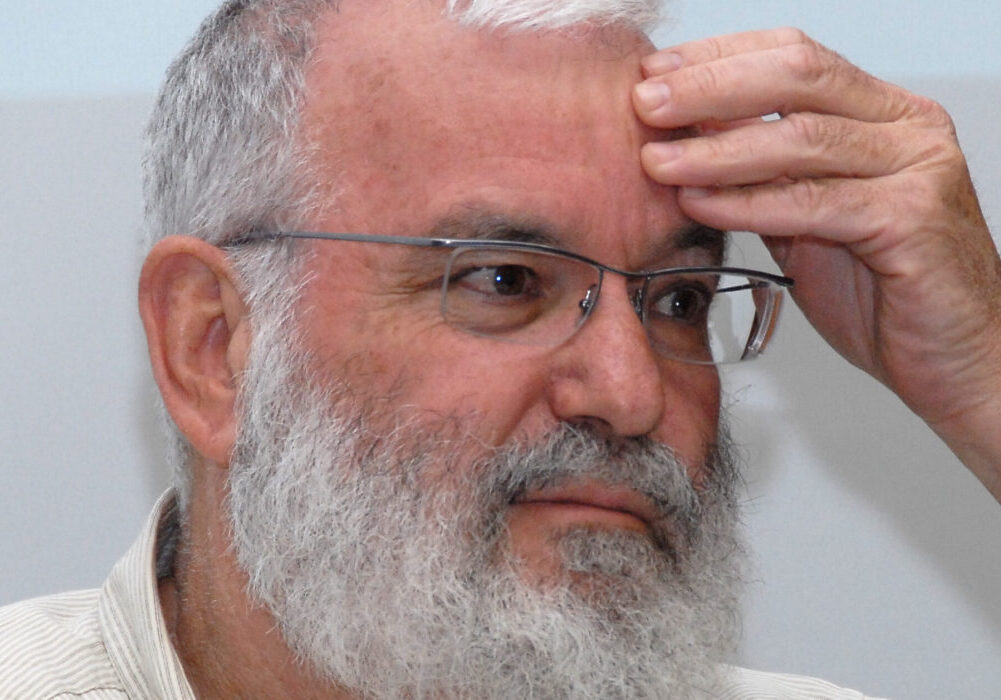

Feb 1, 2018 | Jonathan Spyer

Jonathan Spyer

The protests in Iran widespread in early January appear, for now at least, to be subsiding. The key moment was the decision to task the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) with security in the three provinces that formed the centre of the unrest – Hamadan, Isfahan and Lorestan.

As of late January, it is still too soon to say that the wave has entirely spent itself. Demonstrations were still taking place, despite the IRGC’s announcement of an end to the unrest. In the cities of Sanandaj, Zahedan, Meybod, Abarkuh, Kordkuy, Aqqala, Alvand and Buin Zahra, among other centres, rallies have been held. But the number of those attending the demonstrations is decreasing.

The wave of unrest was the most intensive to hit the country since 2009. Its details constitute evidence of broad alienation from the regime of a significant section of Iran’s youthful population. The unrest at its height spread to over 80 cities and towns. The average age among those arrested was 25. Demonstrators chanted anti-regime slogans and attacked facilities of the Basij paramilitaries and other regime-associated institutions.

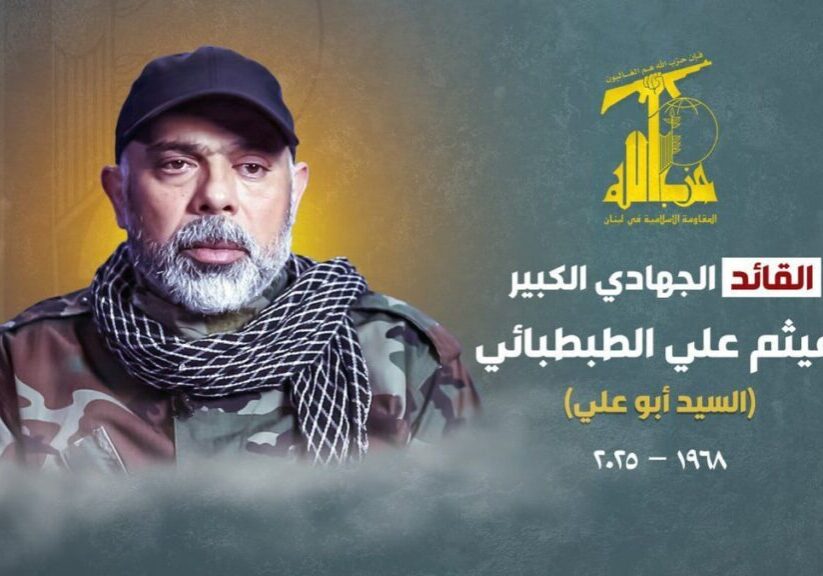

Notably, Teheran’s costly policy of regional interference formed a focus for the protesters’ rage. Slogans such as “Leave Syria, think about us!” and “Death to Hezbollah!” were heard. More general anti-regime slogans, including “We don’t want an Islamic Republic” and “Death to the dictator” were also chanted by demonstrators.

The protests began in the pro-regime, conservative city of Mashhad. Their initial focus was new austerity measures introduced by President Hassan Rouhani. There is evidence that the initial instigators of the demonstrations were themselves from among the hard-line “principalist” opponents of Rouhani.

But these elements did not anticipate the rapid growth of the demonstrations or their intensity. The regime, clearly taken by surprise, reacted in the only way it knows – with a strong hand. Twenty-two people are dead. Hundreds more are wounded.

A number of conclusions can be drawn from the direction of events so far:

1. For those hoping for the downfall of the Islamist regime, a major absence in the Iranian context is that of a revolutionary “party”. This does not necessarily mean a formal political party but, rather, a revolutionary trend with a level of organisation and popular appeal, a vision for the future and a broad strategy for defeating the Islamist regime. At present, nothing of this type exists in the Iranian context -neither as a network inside the country, nor as a widely respected focus on the outside.

Because of this absence, the 2009 protests, which were concerned with the apparently rigged re-election of then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, were diverted through the election of the “moderate” Rouhani.

The current protests, meanwhile, which are economic in nature, may well be similarly diverted by a combination of a strong hand, some cosmetic concessions, and probably, ironically, also by the scape-goating of the “moderate” president.

Such diversionary moves are possible because of the dispersed and divided nature of the opposition. As long as no nucleus of political (and, probably, military) opposition to the regime emerges, it is difficult to see a way that a wave of unrest can smash the edifice of the Islamic Republic.

2. The regime has been keen, naturally, to blame the unrest on foreign agitators. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s Twitter feed suggested that a “pattern activating these events” was apparent. According to the Supreme Leader, a “scheme by the US and Zionists” with money from a “wealthy government near the Persian Gulf” (obviously Saudi Arabia) was responsible.

Given the Iranian regime’s penchant for interference in neighbouring countries – with Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen chief among them – it is tempting to hope that the Supreme Leader’s fears are justified. There is, however, no actual evidence to support such a claim.

In US President Donald Trump’s recent speech outlining his national security strategy, he referred to Iran as “the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism” and identified the need to “neutralise Iranian malign influence.”

One way to help the achievement of the latter goal would be to keep the Iranian home fires burning. Teheran foments unrest in neighbouring countries in order to keep neighbours weak. There is now an opportunity to return the compliment. There are a variety of ways that this might be achieved – from ensuring that protesters and demonstrators remain organised and in communication with one another, to punitive means to disincentivise those countries and individuals assisting the regime in acquiring the means of repression.

3. Among the most difficult type of people to unseat from power through revolution are revolutionaries themselves – at least as long as the revolutionary elite does not begin to crumble from within. There are as yet no signs of this in Iran. Rather, the rising force within the elite is precisely that force most committed to the values of the Islamic Revolution of 1979 (and to spreading its influence into neighbouring lands) – namely, the IRGC and associated hard-line figures.

The rising, militant elements within the regime were themselves participants as young men in the revolution of 1979. Even if there were a similarly determined and organised leadership seeking to make revolution against the Islamic Republic, it would find this cadre a tough nut to crack. And as we have seen above, currently there is not.

Nevertheless, the protests were significant. They point to the sharp fissures within Iranian society and the extent to which the regime is detached from large sections of the population and its wants and needs.

The guardians of the Islamic Republic of Iran have in recent years proved masters at identifying and exploiting the fissures in neighbouring societies. The field is now ripe for this process to turn into a two-way street, depending on the will and the ability of Iran’s opponents to recognise the opportunity and make use of it.

Dr. Jonathan Spyer is Director of the Rubin Centre (formerly the GLORIA Centre), IDC Herzliya, and a fellow at the Middle East Forum. He is the author of Days of the Fall: A Reporter’s Journey in the Syria and Iraq Wars (Routledge, 2017) and The Transforming Fire: The Rise of the Israel-Islamist Conflict (Continuum, 2010). © Jerusalem Post (www.jpost.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.