Australia/Israel Review

Stuck in the Middle

Feb 28, 2012 | Amotz Asa-El

Amotz Asa-El

Half-a-decade after it won its first and last general election, Israel’s political centre is scrambling for a future in a rapidly changing ideological landscape.

At the heart of the jockeying is a three-way contest over the leadership of the main Israeli opposition party, Kadima, and the emergence of a new rival to the party for the middle of the road voter.

Except for Kadima’s victory in 2006, Israel’s 18 general elections were all won either by Likud or Labor, the pair whose historic rivalry reflected divides between nationalists and socialists, as well as gaps between traditionalists and secularists, and, in some years, also tensions between rich and poor and between Jews of European and Mideastern origins.

For decades, the most dominant difference between the two was the attitude toward the Arab-Israeli conflict. Labor said peace could be obtained through territorial compromises, Likud said such concessions would not produce peace, and that the land at stake, the cradle of Jewish history, could not be relinquished. It therefore set out to settle Jews on it.

The common denominator between these two opposing schools was the insistence that the conflict was the most pressing issue in Israel’s public life. Since then, both parties have been humbled in their views, as ultimately conceded by two of the main ideological antagonists: Likud’s Ariel Sharon, who led efforts to settle the West Bank and Gaza, and Labor’s Shimon Peres, who led efforts to trade land for peace.

Last decade’s Palestinian violence made each in his turn abandon his original views. Peres, when he backed the construction of the anti-terror barrier, effectively conceded delivering peace would be more complex than he suggested when he took Israel to Oslo; and Sharon, when he built that same barrier, and especially when he led the retreat from Gaza, conceded that the Greater Israel vision he once embodied was impractical.

That was the backdrop to the emergence of Kadima, the centrist party Sharon and Peres established with other Likud and Labor veterans who had grown disillusioned with their previous positions vis-à-vis the conflict. This improbable welding of long-standing rivals struck a chord with the mainstream public, whose attitude to the conflict had anyhow always been less rigid than Sharon’s and Peres’. This is what brought victory to Kadima in 2006 even after Sharon was incapacitated by a massive stroke soon after establishing the party.

Since then, however, Kadima has lost most of its mystique.

What began with a three-year incumbency marred by moral failures – as Kadima’s finance minister was jailed for embezzlement in a previous position, and party leader Ehud Olmert resigned as prime minister due to his own indictment – was followed by political failures under new party leader Tzipi Livni.

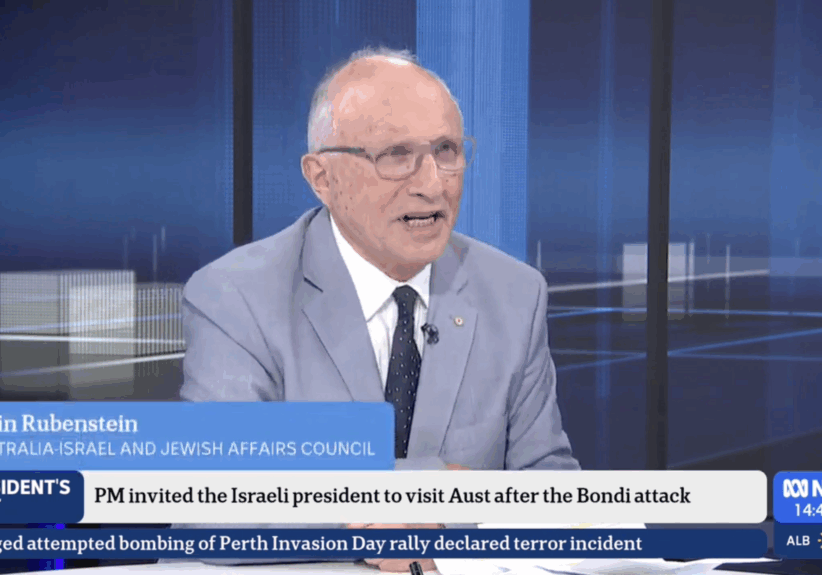

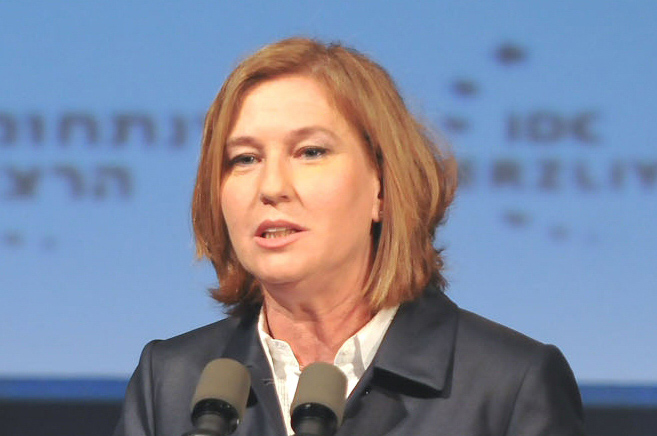

Livni, who had served as Olmert’s foreign minister and Sharon’s justice minister, failed to keep the party united behind her. She managed to preserve the party’s electoral following, just under a quarter of the legislature, but she lost the premiership to Netanyahu’s right-wing bloc. For the three subsequent years, she has been challenged from within by Shaul Mofaz, who was Sharon’s defence minister and before that the IDF’s chief of staff.

Having nearly defeated Livni in a primary election in 2009, Mofaz never accepted her leadership. As Netanyahu’s coalition endured, and the Prime Minister’s grip on power proved solid, Mofaz demanded a new contest for the party’s leadership. Initially Livni withstood the pressure, but when Netanyahu announced a primary election for his own party’s leadership (which he won decisively on Jan. 31), Livni gave in, and agreed to hold a primary election for Kadima’s leadership on March 27.

Mofaz and Livni don’t necessarily represent opposing political schools of thought, but they do come from radically different social backgrounds. Mofaz was born to a family of poor immigrants from Iran, and raised in provincial Eilat during the 1950s. Livni was raised in well-to-do northern Tel Aviv by a Knesset Member who was one of Menachem Begin’s closest lieutenants during his years as an underground leader.

Mofaz’s main argument against Livni is that under her leadership the party risks sinking into oblivion by failing to impact the country’s course, let alone set its agenda. Livni counters that while in Opposition one’s task is not to shape events, but to offer an alternative to those who shape events. While Mofaz failed to explain how he would have impacted events from Opposition, a third contestant joined the race, armed with a plan for how to make Kadima impact events. “Once elected as party leader,” says Avi Dichter, the former head of the Shin Bet who later served as minister of internal security, “I will immediately enter negotiations with Netanyahu and have Kadima join his government.”

Indeed, if she ends up unseated later this month, Livni will likely regret, in hindsight, her decision three years ago to lead Kadima into Opposition, a choice she made via a series of quick telephone calls rather than through an orderly party debate. Had they held cabinet positions, Livni’s restless colleagues might have been busier than they are while languishing in the Opposition. But Livni made an arguably bigger misjudgment when she made the peace process Kadima’s main political issue, even while the focus of Israel’s political system, and of people in the streets, was moving away from foreign affairs to domestic issues.

Pollsters, lacking access to eligible voters for the internal Kadima primary contest, are avoiding predictions, having failed to foresee the narrowness of Livni’s victory over Mofaz last time they faced off. Pundits agree, however, that Kadima is fast losing its electoral following, a diagnosis enhanced by the fact that Livni and Mofaz now say they will not be able to work with each other again. Over the years, Israeli voters repeatedly punished parties whose leaders fought in public. It happened to Labor when Peres and Yitzhak Rabin were at loggerheads, and it happened to Likud when Yitzhak Shamir sparred with his foreign minister, David Levy.

While Kadima’s antagonists were preparing their showdown, an entirely new contestant entered the fray, posing a threat the party would not have been able to ignore even if it was united.

Charismatic, popular, and politically untested, TV journalist Yair Lapid, 49, resigned his job as anchor of Channel 2’s highly rated Friday night news to enter politics. Lapid, who also has a widely read column in the mass circulation Yediot Aharonot’s weekend edition, avoids interviews, preferring for now to correspond with the public through his Facebook page. His views, however, are famously centrist, as were those of his late father Tommy Lapid, whose centrist party Shinui, or ‘Change,’ won more than a tenth of the electorate and became Ariel Sharon’s strategic ally in 2003.

Kadima ended up siphoning off that precursor’s entire following. Now Lapid is out to reclaim his late father’s legacy. Yet the elder Lapid’s political program, a combination of economic liberalism, anti-religious militancy, and diplomatic flexibility, may now prove passé.

The idea of treading a middle road between Greater Israel and Land for Peace is today neither new nor relevant; almost everybody is there, especially after Netanyahu adopted the two-state solution. And as for economic liberalism, following last summer’s social protests throughout Israel, it may prove a liability. The youngsters who took to the streets may not like Lapid’s perceived closeness with the moneyed elite. On that front, Lapid seems to be in the same boat with Kadima, which was caught off guard by the summer’s protests and emerged from them perceived as an anachronism.

Where Lapid can outflank Kadima is on the religious issue. Though unlike his father in actually appreciating tradition and a member of a Reform congregation in Tel Aviv, Yair Lapid will likely make the separation of religion and state a central cause, as his father did. He can play up the demand, highly popular among swing voters, to abolish ultra-Orthodox exemptions from military or national service. Even so, Lapid might find that the younger electorate is more attracted to Labor’s reinvigorated social-democrats, now led by another prominent former journalist, Shelly Yachimovich.

Beyond the ideological issues will lurk Lapid’s own personal popularity and that of whoever else will make-up his new party list, which may prove the most interesting. Lapid has promised to field a party list containing no incumbent politicians – a tall order, but one that, if accomplished, will present a perfect opposite to Kadima, whose representatives are all products of the existing political system. So far there has been very little name-dropping. Former head of the Mossad Meir Dagan has been touted as one possible recruit for Lapid’s party, but he has yet to confirm any affiliation. Another name that has been mentioned is popular modern-Orthodox Rabbi Shai Piron, who might indeed indicate a break with convention that could excite a sizeable electorate.

The fog currently blanketing the battle for Israel’s political centre will likely soon start clearing. By April, Israelis will know who Kadima’s leader will be, and by no later than the end of the year, Lapid will likely tell Israel what platform, colleagues, and strategy he has chosen. And then, in the general election (scheduled for next year, although Netanyahu may call a poll earlier) Israel will tell Kadima and Lapid, whether it still cares for what until recently was an exciting political innovation called centrism.

Tags: Israel