Australia/Israel Review

Israel anticipates some bad chemistry

Sep 18, 2013 | Amotz Asa-El

Amotz Asa-El

As the plot surrounding Syria’s chemical weapons continued to thicken, Israelis of all walks crowded the narrow alleys leading to Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall, where thousands were humming the season’s ancient penitentiary prayers known as Selichot (“apologies”).

News of the Russian-sponsored deal that would potentially end the international crisis non-violently broke three days ahead of the Day of Atonement, when Jews scrutinise their moral conduct over the past year, and vow to improve it in the next.

Despite this timing, no one expected the main protagonists in Syria’s tragedy to repent. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad cannot be trusted to fulfil his commitments, said Israeli President Shimon Peres in response to the Russian proposal, whereby Syria would reveal to foreign inspectors its chemical arsenal, sign the Chemical Weapons Convention, and then destroy or transfer its arsenal.

The civil war’s explosions and smoke clouds can be heard and seen from Israel’s northeastern border on the Golan Heights, but Jerusalem remains strictly neutral. The field hospital the IDF opened in the Golan Heights for Syrian casualties treats them regardless of their backgrounds.

At the same time, Israeli pundits differ on the meaning of the war’s latest twist.

According to Tel Aviv University’s Prof. Eyal Zisser, an expert on Syrian affairs, the chemical-weapons deal may effectively grant Assad victory in the civil war. President Vladimir Putin’s reported assurance that, in return for his chemical disarmament, Assad would receive expanded arms shipments from Russia including fighter jets and spare parts for his battle-worn artillery and tanks, would give Assad what he needs in order to strike the decisive blow required to end the current stalemate according to Zisser.

However, according to veteran Middle East expert Ehud Ya’ari of Israel’s Channel 2 TV news, Assad emerges from the deal weakened and also disgraced, forced to compromise his sovereignty and take orders from Moscow. According to this thesis, the Syrian civil war will continue for a long time, and it is doubtful there will be a clear winner even when after it finally ends.

It appears impossible to predict how Assad will conduct his war after accepting having been effectively disciplined by Russia.

The Syrian leader and the Alawite minority he represents understand their situation as a zero-sum game, whereby they have only two choices: either subdue or be subdued by their country’s Sunni majority. That is perhaps what made him gradually upgrade his attacks on civilian targets, which escalated over the past two years from light arms to armour, and then from artillery to gunships and fighter bombers, and finally to non-conventional weapons.

The chemical attack on August 21 on the outskirts of Damascus, which reportedly killed more than a thousand civilians in their homes, apparently reflected a Syrian assessment that America would not make good on its threat to respond to gas attacks, since it had ignored smaller chemical attacks previously.

In this regard, Assad overplayed his hand. Even if he remains chemically-armed despite the Russian initiative – as Peres cautioned is likely – Syria’s chemical option, and its willingness to use it, has been exposed. Assad successfully used this weapon only sporadically and locally, but has apparently lost the ability to use it strategically, as a game changer.

What, then, is the chemical showdown’s impact on the civil war’s complex regional and international diplomacy?

Former Mossad head Ephraim Halevi believes that the chemical-weapons crisis has greatly enhanced Russia’s position in the Middle East. Forty years after it lost its standing in the Arab world following the Yom Kippur War, Russia is making a comeback, Halevi argues. Moscow, he says, is convincing potential Arab clients that it is a reliable sponsor.

Russia’s situation is also precarious. Financially, the business it once did in Libya has yet to be restored, while the cash which destitute Syria owes Russia will take years to repay, at best. And diplomatically, while Vladimir Putin’s quest to humble America seems to have been satisfied in Syria, Assad’s humanitarian excesses may have gone too far even for Putin. While prepared to take sides in a distant civil war, Putin does not want to be seen in the Sunni world as the man who first supplied and then backed chemical attacks on defenceless Sunni families.

In addition, Israeli experts caution that Iran and Turkey will now study closely the impact of Russia’s latest ploy on their own conflicting interests.

Teheran has reason to feel relieved, as its proxy has been saved just when it seemed Assad may be poised to exit the stage prematurely, or at least take a major hit. Ankara, which wants Assad out and a Sunni regime installed in Damascus, might conclude from the situation that it should prepare for a more active involvement in the civil war – in opposition to both Assad and Russia, a historic enemy of Turkey that is now stepping on Ankara’s toes in an increasingly painful way.

Such, then, is the Israeli reading of the Syrian war’s non-Israeli aspects. The direct impact on Israel is easier to assess.

Militarily, the Syrian army has been bruised in a way that will reduce the immediate threat it can pose to Israel. Assad’s troops have lost much materiel as well as many commanders and junior officers. This is true even if the chemical arsenal survives, but doubly so if it does not.

More importantly, Syria is disintegrating, both as a polity and as a society.

Even if Assad retains his control of Damascus, the impression in Israel is that millions of Syrians will never return to following his lead, or indeed that of any Alawite. The Kurdish enclave in Syria’s northeast already has effectively seceded, and is poised to slowly join the Iraqi Kurdish autonomy to its east. However, just how the rest of Syria will ultimately rearrange itself is much less clear.

The Sunni effort is to snatch Damascus and push Assad and his key supporters west, into the coastal strip and adjacent mountains, where the Alawites have been centred for centuries. Assad’s priority is to retain Damascus and consolidate a corridor from there to the coast. This is evidently the context in which Assad acted when he launched his gas attack outside Damascus.

In addition to ever-cryptic Syria, the crisis has also made it difficult to predict and decipher President Barack Obama.

“He erred three times,” argued Israel’s most influential columnist, Nahum Barnea of the mass circulation Yediot Aharonot: First, when he declared a red line concerning chemical weapons; then, when he let Secretary of State John Kerry warn Assad as harshly as he did, thus raising expectations for swift military action; and finally, when he decided to outsource his decision to Congress, a move Barnea described as “strange at best, derelict at worst.”

Subsequent news that Obama and Putin had been discussing Syria all along has tempered such judgments concerning Obama’s wisdom. However, it did little to assuage growing doubts in Israel concerning Obama’s temperamental preparedness to attack Iran, should it decide to follow Assad’s script and provoke America by moving to produce a nuclear weapon.

Some now argue that Obama’s delivery of a stern case for military action on Syria in a speech on Sept. 10 should make the Iranians conclude that America does confront those who violate its red lines, and that Teheran will now avoid testing America on the nuclear front. However, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appears to disagree, despite publicly backing the Syria deal in meetings with US Secretary of State John Kerry.

Speaking to naval officers the day after the Russian proposal was made public, Netanyahu first addressed the Syrian crisis and then its Iranian implications.

Concerning Syria, he indirectly criticised Obama, saying that the international community must not only verify that Syria’s chemical disarmament is carried out, but also that “whoever uses weapons of mass destruction will be made to pay for that.”

As for Iran, Netanyahu insinuated he could not rely on Obama, though he obviously didn’t say it in so many words. Instead, the Prime Minister enlisted Hillel the Sage, who lived in Roman-era Judea 2,000 years ago, and whose self-help adage is a famous Hebrew saying to this day: “If I am not for myself,” quoted Netanyahu, “who will be for me?”

Tags: Israel

RELATED ARTICLES

Security concerns over Herzog visit a terrible indictment: Joel Burnie on Sky News

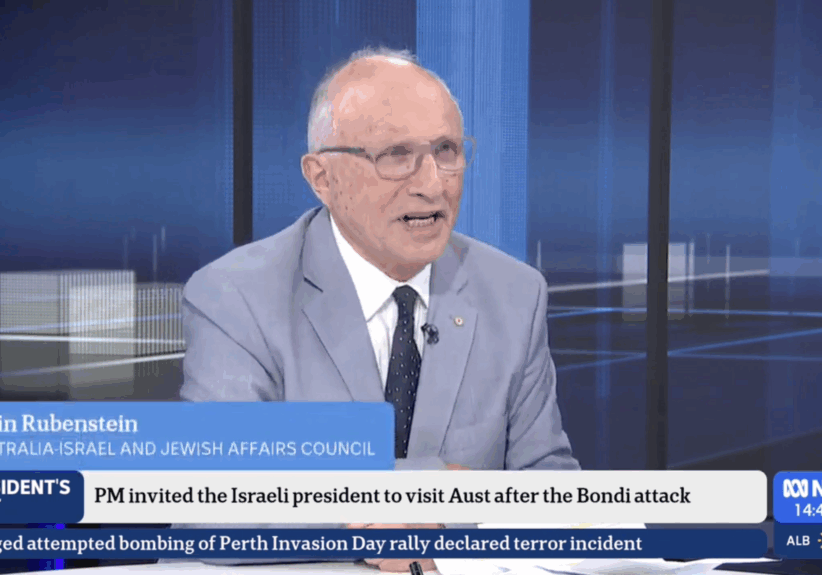

Allegations against Israeli President Herzog are absurd: Colin Rubenstein on ABC News