Australia/Israel Review

Yes, We Can

Mar 31, 2009 | Frederick W. Kagan, Max Boot & Kimberly Kagan

The parameters of victory in Afghanistan

By Frederick W. Kagan, Max Boot & Kimberly Kagan

If you believe the headlines, Afghanistan is “the graveyard of empires,” a “quagmire” and a “fiasco”. In the media’s imagination, the Taliban are on the march and Kabul is on the verge of falling to a resurgent insurgency that already controls much of the countryside. Increasing numbers of voices counsel that the war is unwinnable and that we need to radically “downsize” our objectives.

Evidence to support the pessimists isn’t hard to find. Violence has increased every year since 2001. The United Nations recently reported that there was an especially big jump last year, with civilian deaths up nearly 40%, from 1,523 in 2007 to 2,118 in 2008. Coalition deaths were up 27%, rising to 294 in 2008 from 232 in 2007. Meanwhile the number of Afghans surveyed who said that their country was headed in the right direction fell to 40%, down from 54% in 2007, with security rated as by far the worst problem, outpacing corruption and the economy.

The sense of doom is fed by news reports on spectacular attacks, such as the Feb. 11 raid in which suicide bombers and gunmen attacked several government sites across Kabul, killing at least 20 people.

Fears of impending disaster are hard to sustain, however, if you actually spend some time in Afghanistan, as we did recently at the invitation of General David Petraeus, chief of US Central Command. We spent eight days travelling from the snow-capped peaks of Kunar province near the border with Pakistan in the east to the wind-blown deserts of Farah province in the west near the border with Iran. Along the way we talked with countless coalition soldiers, ranging from privates to a four-star general. We also attended a tribal shura or council – a fantastic affair straight out of an earlier century – to sample opinion among bearded Afghan elders. What we found is a situation that is cause for concern but far short of catastrophe – and one that is likely to improve before long.

To start with, much of the north, centre and west remains relatively secure. Attacks have increased in those areas but are still extremely low. Figures showing large increases are deceptive because the total numbers to begin with were so small and because most of the attacks produced few if any casualties. For instance, the Brookings Afghanistan Index shows a 48% increase in attacks last year in Regional Command-Capital, which encompasses Kabul and its environs and has a population of more than 4 million people. But the total (157 attacks in 2008) would have represented just four days of violence in Baghdad in the summer of 2006.

As these figures suggest, the capital of Afghanistan is remarkably peaceful. Entire weeks go by without an insurgent attack and the streets bustle with cars and pedestrians. Coalition officials drive around in lightly armoured SUVs, something that would have been unthinkable in Baghdad. The idea that Kabul is under siege is a figment of the news media’s imagination.

Equally impressive progress is being made in Jalalabad, a city of perhaps 400,000 in eastern Afghanistan’s Nangarhar Province. Violence is low; US troops don’t even patrol the city, leaving that job to the Afghan National Security Forces. Economic development is booming, spurred by “Nangarhar Inc.”, a development plan overseen by a US-run Provincial Reconstruction Team in cooperation with local officials.

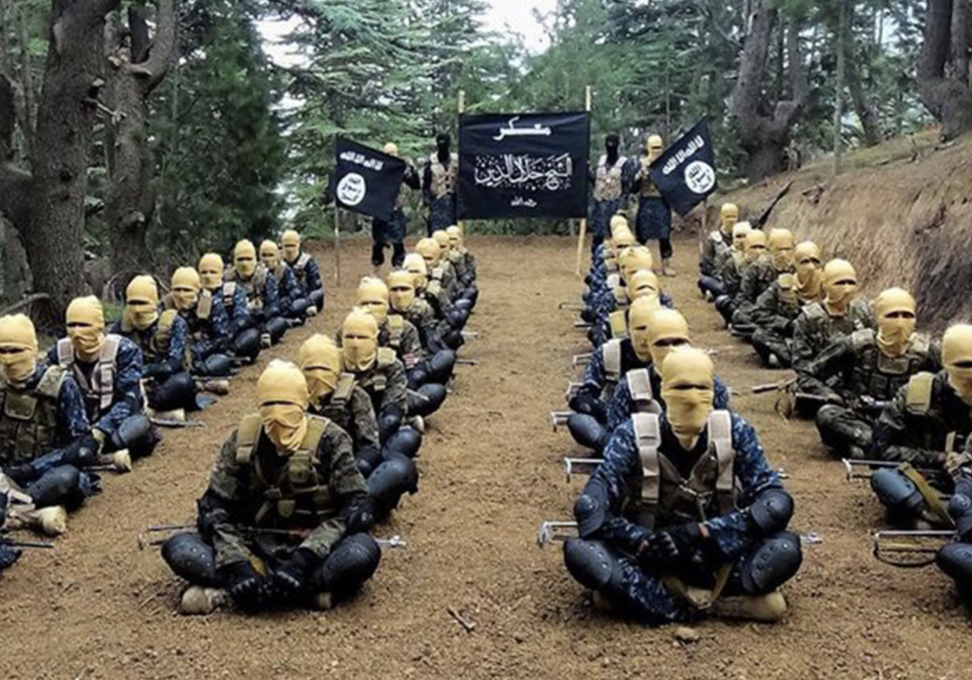

Not all of Regional Command-East (RC-East) is as peaceful or prosperous. This remains the second most violent region in the country, behind only Regional Command-South. This is hardly surprising since RC-East is located along the long, mountainous eastern border with Pakistan, which has become a safe haven for numerous Islamist terrorist groups. With rumoured assistance from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI), many of these groups are carrying out cross-border attacks in Afghanistan in pursuit of a bewildering array of strategies and objectives. Officers at the Bagram headquarters of the 101st Airborne Division, who run RC-East, have taken to speaking of an insurgent “syndicate”. Their charts draw numerous intersecting lines between nine different groups which alternately compete and cooperate with one another.

What unites these groups beyond a shared antipathy to the modern world, a propensity for violence and a devotion to extremist forms of Islam? Some central direction is provided by three shuras sitting in the western Pakistani cities of Quetta, Miram Shah and Peshawar. Connections with the ISI also link most of these groups together. But the shuras provide only broad direction. Individual groups and subgroups act with considerable autonomy. That is a big advantage for the government of Afghanistan and its allies, since there is no Ho Chi Minh or Mao Zedong to knit together a far-flung insurgency into a cohesive movement.

Even without much central direction, however, these insurgent groups have been pursuing a loose-knit strategy whose contours are faintly discernible to International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), as the NATO coalition in Afghanistan is formally named. Some of the southern Taliban are pushing toward Kandahar, the central city of southern Afghanistan and a traditional Taliban stronghold. The northern groups are pushing toward Kabul. They are concentrating attacks on coalition and Afghan security forces in the countryside, hoping to drive them into the major cities and besiege them there. Eventually they hope to inflict enough pain on the coalition to force public opinion in Europe and North America to demand a withdrawal.

In the meantime, to exert control of rural areas, they seek to intimidate anyone who dares to cooperate with the infidel “occupiers”. The insurgents often post threatening “night letters” warning those who work with the foreigners and sometimes follow up by beheading supposed collaborators. Through such actions they have created a feeling of insecurity even in areas of Afghanistan where the objective levels of violence are not that high.

Unlike in Iraq, the insurgents in Afghanistan are not indiscriminately slaughtering the civilian population. Some are making greater use of suicide bombers, but their targets are largely the Afghan National Security Forces, coalition forces and government officials. Such attacks, however, can all too easily go wrong. We visited a district centre, in the Mandozai District of Khost Province, that had been hit on Dec. 28. Guards prevented a suicide bomber driving a car from entering the compound, so he blew himself up at the gate, killing 14 children and two adults.

Whereas Iraqi insurgents might have revelled in such violence, their Afghan counterparts are more sensitive to the need to cultivate public opinion. They prefer for the coalition to kill civilians – something they make much more likely by hiding among civilians. The insurgents have made skilful use of collateral damage inflicted by the coalition, especially in air raids and what are known as “night raids” when Special Operations Forces swoop down on insurgents’ homes after dark. The guerrillas have done a brilliant job of trumpeting civilian casualties – usually exaggerated, sometimes invented – to accuse the coalition of brutality. Wittingly or not, Afghan President Hamid Karzai has helped the enemy by harping on coalition-caused casualties while all but ignoring in his public pronouncements mention of the far greater number of deaths inflicted by the guerrillas.

When it comes to operations against coalition forces, the insurgents, like their Iraqi counterparts, rely primarily on improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The number set off increased from 2,569 in 2007 to 3,742 in 2008. The bombs employed in Afghanistan are, however, less sophisticated than in Iraq. So far Explosively Formed Penetrators, the armour-piercing munitions that Iran shipped to Iraqi terrorists, have not made an appearance in Afghanistan. So coalition troops have a fair degree of protection as long as they stay in Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles, 2,000 of which have been shipped to Afghanistan.

While not as sophisticated as Iraqi terrorists in the dark arts of the IED, Afghan insurgents are rated more proficient in light infantry tactics thanks to the training they have received in Pakistan. “This is a capable opponent,” says Brigadier General Mark Milley, deputy commander of the 101st Airborne Division. Insurgents most often operate in groups of five to 15, but sometimes they can mass several hundred fighters. When they get into firefights, they sometimes draw close enough to use their weapons effectively, and they have shown the ability to fire and manoeuvre in squad, platoon, and even company-sized formations.

In the east, the insurgents are helped immeasurably by the terrain – some of the world’s tallest mountains split up the population into numerous small valleys that are cut off from one another, as well as from the outside world. “This is perfect guerrilla country,” Milley remarked as we flew with him in a Black Hawk helicopter over the snowy Hindu Kush.

One should not exaggerate the combat prowess of the insurgents. Occasionally, it is true, they are able to catch a coalition unit off guard and inflict considerable casualties. Two such incidents occurred last year in RC-East when a newly arrived French detachment suffered nine killed in action and when a new, still-unfinished American outpost was hit so heavily that nine American soldiers were killed. But such incidents are the exception, not the rule. Most insurgent attacks inflict no casualties on coalition forces and result in devastating losses for the attackers when coalition troops call in air or artillery strikes. The Afghan National Army (ANA) and Afghan National Police are less well armed and trained and so suffer more heavily, but the ANA, at least, has shown itself superior to the enemy in every major firefight.

More effective from the enemy standpoint have been attacks on coalition lines of communication. The Pakistan Taliban have been attacking private trucks hired to lug supplies from the port of Karachi, Pakistan, into Afghanistan. Their Afghan counterparts have also been mining roads and blowing up culverts and bridges, replicating tactics that the mujahedeen once used against the Red Army. The Russians have contributed to the coalition’s difficulties by pressuring Kyrgyzstan to close the US air base at Manas, which is a primary hub for aerial tankers supporting coalition aircraft as well as a transit point for troops flying in and out of Afghanistan.

Given the hyperbolic reporting on these supply woes, when we arrived we half expected to find troops cowering in unheated hovels without sufficient bullets to fire, fuel to move, or food to fill their bellies. Nothing could be further from the truth. US forces in Afghanistan appear to be as well supplied as their counterparts in Iraq.

Contrary to the gloomy impression prevalent back home, commanders on the ground expressed confidence that they would be able to beat back the insurgency with the additional US troops now flowing in. The 38,000 US troops currently in Afghanistan will be joined by 17,000 more by this summer thanks to reinforcements wisely authorised by President Obama, and more may be coming later. One Brigade Combat Team, part of an earlier reinforcement authorised by former President Bush, had just arrived in RC-East when we were visiting. With the addition of Polish and French forces – which come without any of the caveats that have hindered the effectiveness of most other NATO contingents – RC-East has seen a considerable boost in troop strength. Just a few weeks ago, Wardak and Logar provinces south of Kabul were garrisoned by only 400 US troops. Now they will have more than 4,000.

The transformation will be even more dramatic in RC-South, which Gen. David McKiernan, the ISAF commander, currently describes as a “stalemate”. An officer in the south told us, “We’ve said we’re doing counterinsurgency in the south but we’ve never resourced it.” That is about to change. This region will receive almost all of the 17,000 additional US troops, including a Marine Expeditionary Brigade and an Army Stryker Brigade Combat Team, to reinforce the existing force of just 3,300 Americans. (There are also 20,000 other troops in RC-South from 16 nations, the biggest contingents being 8,200 Brits, 3,500 Canadians, 2,100 Dutch and 1,050 Australians.) Beyond this ground combat power, there will be a major increase in intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance assets and a doubling of rotary airpower.

This represents a significant change in the correlation of forces on the battlefield and coalition commanders expect that it will allow them to take the fight to the enemy in ways that were impossible before. Their goal is to conduct “shape, clear, hold and build” operations in conjunction with Afghan allies. Their expectation is that the insurgents will violently contest their efforts, resulting in an increase in attacks and casualties during the summer fighting season. But coalition commanders are fully confident that before long, perhaps by the fall, insurgents will have taken a licking, forcing them to retreat. As one American officer put it to us, “An awful lot of bad guys are going to get killed in the next four to six months.” They recall what happened last year in Garmsir District in Helmand Province, when the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit arrived in the spring. The 2,500 Marines faced a hard fight for a month, but gradually they drove out the enemy, allowing bazaars to reopen, shuras to be conducted and development assistance to flow.

It is not, of course, anyone’s intention that foreign forces carry the bulk of the fight in Afghanistan indefinitely. And they won’t have to. The ANA has already established itself as the most trusted indigenous institution in the entire country. This ethnically balanced force has performed capably and bravely in battles too numerous to count. It has taken heavy losses, but it has not suffered heavy desertions. “The enemy cannot fight us face to face,” Brig. Gen. Sher Mohammad Zazai, commander of the ANA’s 205th Corps based in Kandahar, told us proudly.

The problem is that the ANA is still far too small, numbering only 80,000 soldiers. The Afghan National Police, which is less effective and more corrupt, has another 70,000 personnel. That’s 150,000 security personnel for a country of 30 million. By way of comparison, Iraq, which has a smaller population, has more than 500,000 men in its army and police forces. The current plan to expand the ANA – it is supposed to reach 134,000 men by the end of 2011 – is completely inadequate to the size of the challenge. Since the government of Afghanistan lacks the money and resources to do the job itself, the US and its allies will have to fund and support a much larger (and, if possible, much faster) expansion of the Afghan National Security Forces. We should immediately commit to the goal of a 250,000-strong ANA. Afghan troops also need better equipment – everything from armoured vehicles and helicopters to night-vision devices – and they need it as soon as possible.

No one claims that force alone can defeat the insurgents (Gen. Petraeus recently told Time magazine that “you cannot kill your way out of an insurgency”), but clearly a greater level of security in the east and south is essential for progress on political, social, or economic development. In that regard one of the biggest problems cited by Afghans is the corruption of their own government. The symbol of this problem is Ahmed Wali Karzai, brother of President Hamid Karzai, who is the head of the Kandahar Provincial Council and the most powerful man in this crucial southern province. Numerous reports link him to the drug trade, although no definitive evidence has ever been made public and he has denied the charges. Nevertheless there is a widespread impression that the president’s brother is involved in narco-trafficking and that the president is running protection for him. Numerous other, lower-profile government officials (including a number of governors) are said to be connected with the illicit narcotics trade, which is Afghanistan’s leading industry.

The drug business, centred in the southern provinces, produces 90% of the world’s opium, worth an estimated US$4 billion a year. Of that total, the United Nations estimates US$500 million goes into the hands of the insurgents, who provide protection for the narco-traffickers and collect taxes from poppy farmers. That makes the drug trade a major concern for the coalition. Yet NATO’s mandate does not allow coalition troops to target the drug lords directly. That is a job reserved for Afghanistan’s counter-narcotics forces, which are advised by DynCorp contractors paid by the US State Department. But ISAF forces are starting to get into the anti-drug fight because the poppy-eradication forces are protected by Afghan army troops who have with them embedded American advisers.

It makes sense for ISAF troops to take on the corrosive drug trade, which funds the insurgency and undermines governmental legitimacy, but doing it through this backdoor route carries a heavy cost in inefficiency. As things now stand, counter-drug efforts are poorly integrated with a larger counterinsurgency strategy in the south.

Developing such a strategy has been, to put it mildly, challenging, given the competing demands of 41 countries that are represented in ISAF. Few of them will even admit that they are fighting a “war”, a word that is not used in NATO’s plans. Some of the foreign contingents – notably the British, Australians, Canadians and French – are willing to fight, take risks and suffer losses; but many others refuse to leave their bases.

Trying to bring some coherence to this unwieldy coalition is Gen. McKiernan, an American four-star who is commander of US forces in Afghanistan as well as ISAF.

McKiernan’s task is made considerably more difficult by the polyglot nature of ISAF’s headquarters in Kabul and Kandahar, which are designed to maximise coalition representation rather than military effectiveness. In the US military, headquarters staff will train together for a year before deploying into a combat zone. In ISAF, headquarters staffs from many different nations assemble only a few weeks before heading to Afghanistan. Making the problem worse, while most Americans stay in Afghanistan for at least a year, most other NATO soldiers are on four- to six-month rotations, making it almost impossible to achieve any coherence or continuity. Even NATO officers privately admit that the resulting arrangement is, as one of them put it, “partially dysfunctional.” Their American counterparts are more scathing. “You couldn’t pay someone to come up with a more screwed-up structure than we have here,” one colonel in Kabul told us. Yet as long as the top concern is to keep the coalition together, making significant changes involves a diplomatic nightmare.

At some point the United States will have to decide what price it is willing to pay for keeping all of the ISAF contributors happy, most of whom send contingents so small or so heavily limited by caveats that they contribute little or nothing to the success of the mission.

One of the top areas that needs to be addressed is the inability of ISAF forces under their NATO mandate to hold prisoners for more than 96 hours. This is driven by distaste among the Europeans and Canadians for getting involved in detention operations with their whiff of Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo. But the result is that it is self-defeatingly difficult to take enemy fighters off the battlefield. Detainees turned over to Afghan forces are liable to be released because the Afghan legal system has scant ability to process or hold insurgents. This “catch and release” pattern not only undermines the morale of coalition and Afghan forces but also jeopardises the willingness of villagers to cooperate with the coalition, because they know that terrorists they turn in could be back to wreak vengeance within weeks.

The small number of US forces still outside the NATO mandate do have the right to take prisoners, but they are holding only 620 detainees at the Theatre Internment Facility located at Bagram Air Base north of Kabul. Another 350 suspected insurgents are housed at the Afghan National Detention Facility, a wing at the Pul-e-Charkhi prison that has been built and supervised by American personnel but is operated by Afghans. By way of comparison, at the height of the surge in Iraq, US forces were detaining 24,000 people. Although counting the enemy is an inexact science in any counterinsurgency, the estimates we heard suggest that there are at least as many enemy fighters in Afghanistan as in Iraq. It will be hard to pacify the country until more of these terrorists are locked up.

For the long term, that will require putting more efforts into bolstering the rule of law in Afghanistan – building prisons and courts and training judges, lawyers and prison guards. That is something that has not received nearly the priority it deserved, and it has created an opening for the Taliban who operate sharia courts to settle disputes that ought to be settled by tribal elders or government courts.

Even under the best of circumstances, the coalition will face a long, difficult fight in Afghanistan. But it is hardly a mission impossible. It is not even as difficult as the war in Iraq, where the insurgents were better organised and more deadly. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that bringing a measure of stability to Afghanistan will require considerable expenditure of blood and treasure over a number of years. Is it worth it?

Those who answer in the negative point out that Afghanistan no longer hosts substantial concentrations of al-Qaeda. They argue that it is these international terrorists who should be of concern to the United States and that we shouldn’t waste our resources fighting the Taliban and assorted other local malefactors. It is true that today there are more al-Qaeda fighters, to say nothing of leaders, in Pakistan than in Afghanistan. But the most effective steps we can take to target them, using Predators and other assets, are made possible by the coalition troop presence in Afghanistan. If coalition forces pull out of Afghanistan or substantially reduce their presence, the already limited willingness of the government of Pakistan to cooperate with the United States will evaporate. Pakistan will see that the Taliban are heading toward victory and will cut deals with them – something that is already happening but will accelerate if US forces are seen as being on the way out.

A victory for the insurgents in Afghanistan would have baleful consequences on many levels. It would, first of all, be a major morale-boost to the terrorists and a devastating blow to American prestige and credibility. The mujahedeen victory over the Red Army led to the rise of al-Qaeda and hastened the dissolution of the Soviet Union. There is no doubt that al-Qaeda would trumpet an insurgent victory in Afghanistan today as the defeat of another superpower by the jihadists. An insurgent victory would also surely lead to the establishment of major terrorist base camps in Afghanistan of the kind that existed prior to Sept. 11, 2001. Finally, an insurgent victory in Afghanistan would significantly undermine the government in Pakistan. Many of the groups fighting in the Pashtun belt of Afghanistan and Pakistan are as eager to topple the government in Islamabad as the one in Kabul and victory on one side of the border would accelerate their efforts on the other side.

Those who say that we cannot succeed in Afghanistan without fixing Pakistan have it backwards. We cannot begin to improve the situation in Pakistan without improving Afghanistan and it is possible to do that no matter what happens in Pakistan because, for all the cross-border support it receives, the Afghan insurgency remains largely home-grown.

Experience in Iraq showed that the only effective way to deny terrorists sanctuary is to pursue a full-spectrum counterinsurgency strategy that establishes governmental control of contested areas. That means putting coalition and local security forces into villages where they can gain the trust of the locals and thereby secure the intelligence needed to root out terrorists. Otherwise, if coalition forces are only a fleeting presence, locals will never rat out the terrorists for fear of retribution. The security “line of operations” has to be coupled with efforts to promote better governance and economic and social development.

Those who claim that this is a fool’s errand because Afghanistan has never had any effective governance only reveal their own ignorance of that country’s long and proud history. For all its tribalism and internecine warfare, Afghanistan has been an independent country since the 18th century, with such strong monarchs as Dost Mohammad, who drove out a British incursion in 1842 and ruled for 33 years. Under King Mohammad Zahir Shah, who ruled from 1933 to 1973, Afghanistan made considerable economic and political progress, including the adoption of a fairly democratic written constitution. It was relatively peaceful and stable before a Marxist coup in 1978 set off a long period of war and turmoil.

The greatest asset that the United States and its allies have in the battle for Afghanistan’s future is the people of Afghanistan. In a recent poll conducted by ABC, the BBC and ARD, only 4% of Afghans expressed a desire to be ruled by the Taliban. Sunni and Shi’ite insurgents in Iraq enjoyed far higher levels of popular support in their respective communities at the height of the violence. For all their ferocity and cunning, the insurgents in Afghanistan do not offer a viable alternative that can win widespread acceptance. They can only take power if coalition forces give up the fight. To do so would hand Islamist terrorists their most significant – indeed, almost their only – victory since 9/11. It is fully in the power of coalition forces to prevent that dire outcome, but only if they have the popular support back home to finish what they started in 2001.

Frederick W. Kagan is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Max Boot is a contributing editor to the Weekly Standard and the Jeane J. Kirkpatrick senior fellow in National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. Kimberly Kagan is the president of the Institute for the Study of War and the author of The Surge: A Military History. © Weekly Standard, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Afghanistan/ Pakistan