Australia/Israel Review

The Real Iraq

Jul 3, 2006 | Amir Taheri

Some facts you probably don’t know

By Amir Taheri

Spending time in the United States after a tour of Iraq can be a disorienting experience these days. Within hours of arriving there, as I can attest from a recent visit, one is confronted with an image of Iraq that is unrecognisable. It is created in several overlapping ways: through television footage showing the charred remains of vehicles used in suicide attacks, surrounded by wailing women in black and grim-looking men carrying coffins; by armchair strategists and political gurus predicting further doom or pontificating about how the war should have been fought in the first place; by authors of instant-history books making their rounds to dissect the various “fundamental mistakes” committed by the Bush administration; and by reporters, cocooned in hotels in Baghdad, explaining the “carnage” and “chaos” in the streets as signs of the country’s “impending” or “undeclared” civil war.

It would be hard indeed for the average interested citizen to find out on his own just how grossly this image distorts the realities of present-day Iraq. Part of the problem, faced by even the most well-meaning news organisations, is the difficulty of covering so large and complex a subject; naturally, in such circumstances, sensational items rise to the top. But even ostensibly more objective efforts, like the Brookings Institution’s much-cited Iraq Index with its constantly updated array of security, economic, and public-opinion indicators, tell us little about the actual feel of the country on the ground.

For someone like myself who has spent considerable time in Iraq – a country I first visited in 1968 – current reality there is, nevertheless, very different from this conventional wisdom, and so are the prospects for Iraq’s future. It helps to know where to look, what sources to trust, and how to evaluate the present moment against the background of Iraqi and Middle Eastern history.

Since my first encounter with Iraq almost 40 years ago, I have relied on several broad measures of social and economic health to assess the country’s condition. Through good times and bad, these signs have proved remarkably accurate – as accurate, that is, as is possible in human affairs. For some time now, all have been pointing in an unequivocally positive direction.

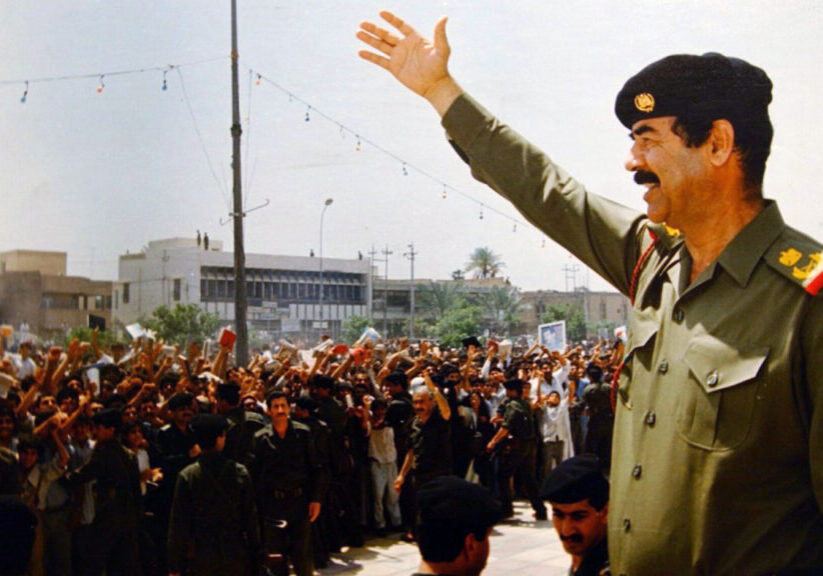

The first sign is refugees. When things have been truly desperate in Iraq – in 1959, 1969, 1971, 1973, 1980, 1988, and 1990 – long queues of Iraqis have formed at the Turkish and Iranian frontiers, hoping to escape. In 1973, for example, when Saddam Hussein decided to expel all those whose ancestors had not been Ottoman citizens before Iraq’s creation as a state, some 1.2 million Iraqis left their homes in the space of just six weeks. This was not the temporary exile of a small group of middle-class professionals and intellectuals, which is a common enough phenomenon in most Arab countries. Rather, it was a departure en masse, affecting people both in small villages and in big cities, and it was a scene regularly repeated under Saddam Hussein.

Since the toppling of Saddam in 2003, this is one highly damaging image we have not seen on our television sets – and we can be sure that we would be seeing it if it were there to be shown. To the contrary, Iraqis, far from fleeing, have been returning home. By the end of 2005, in the most conservative estimate, the number of returnees topped the 1.2 million mark. Many of the camps set up for fleeing Iraqis in Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia since 1959 have now closed down.

A second dependable sign likewise concerns human movement, but of a different kind. This is the flow of religious pilgrims to the Shi’ite shrines in Karbala and Najaf. Whenever things start to go badly in Iraq, this stream is reduced to a trickle and then it dries up completely. From 1991 (when Saddam Hussein massacred Shi’ites involved in a revolt against him) to 2003, there were scarcely any pilgrims to these cities. Since Saddam’s fall, they have been flooded with visitors. In 2005, the holy sites received an estimated 12 million pilgrims, making them the most visited spots in the entire Muslim world, ahead of both Mecca and Medina.

Over 3,000 Iraqi clerics have also returned from exile, and Shi’ite seminaries, which just a few years ago held no more than a few dozen pupils, now boast over 15,000 from 40 different countries. This is because Najaf, the oldest centre of Shi’ite scholarship, is once again able to offer an alternative to Qom, the Iranian “holy city” where a radical and highly politicised version of Shi’ism is taught.

A third sign, this one of the hard economic variety, is the value of the Iraqi dinar, especially as compared with the region’s other major currencies. In the final years of Saddam Hussein’s rule, the Iraqi dinar was in free fall; after 1995, it was no longer even traded in Iran and Kuwait. By contrast, the new dinar, introduced early in 2004, is doing well against both the Kuwaiti dinar and the Iranian rial, having risen by 17 percent against the former and by 23 percent against the latter. The new Iraqi dinar has done well against the US dollar, increasing in value by almost 18 percent between August 2004 and August 2005. The overwhelming majority of Iraqis, and millions of Iranians and Kuwaitis, now treat it as a safe and solid medium of exchange.

My fourth time-tested sign is the level of activity by small and medium-sized businesses. In the past, whenever things have gone downhill in Iraq, large numbers of such enterprises have simply closed down, with the country’s most capable entrepreneurs decamping to Jordan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, the Persian Gulf states, Turkey, Iran, and even Europe and North America. Since liberation, however, Iraq has witnessed a private-sector boom, especially among small and medium-sized businesses.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, as well as numerous private studies, the Iraqi economy has been doing better than any other in the region. The country’s gross domestic product rose to almost US$90 billion in 2004 (the latest year for which figures are available), more than double the output for 2003, and its real growth rate, as estimated by the IMF, was 52.3 per cent. In that same period, exports increased by more than US$3 billion, while the inflation rate fell to 25.4 percent, down from 70 percent in 2002. The unemployment rate was halved, from 60 percent to 30 percent.

Related to this is the level of agricultural activity. Between 1991 and 2003, the country’s farm sector experienced unprecedented decline, in the end leaving almost the entire nation dependent on rations distributed by the United Nations under Oil-for-Food. In the past two years, by contrast, Iraqi agriculture has undergone an equally unprecedented revival. Iraq now exports foodstuffs to neighbouring countries, something that has not happened since the 1950s. Much of the upturn is due to smallholders who, shaking off the collectivist system imposed by the Ba’athists, have retaken control of land that was confiscated decades ago by the state.

Finally, one of the surest indices of the health of Iraqi society has always been its readiness to talk to the outside world. Iraqis are a verbalising people; when they fall silent, life is incontrovertibly becoming hard for them. There have been times, indeed, when one could find scarcely a single Iraqi, whether in Iraq or abroad, prepared to express an opinion on anything remotely political. This is what Kanan Makiya meant when he described Saddam Hussein’s regime as a “republic of fear.”

Today, again by way of dramatic contrast, Iraqis are voluble to a fault. Talk radio, television talk-shows, and Internet blogs are all the rage, while heated debate is the order of the day in shops, tea-houses, bazaars, mosques, offices, and private homes. A “catharsis” is how Luay Abdulilah, the Iraqi short-story writer and diarist, describes it. “This is one way of taking revenge against decades of deadly silence.” Moreover, a vast network of independent media has emerged in Iraq, including over 100 privately-owned newspapers and magazines and more than two dozen radio and television stations. To anyone familiar with the state of the media in the Arab world, it is a truism that Iraq today is the place where freedom of expression is most effectively exercised.

That an experienced observer of Iraq with a sense of history can point to so many positive factors in the country’s present condition will not do much, of course, to sway the more determined critics of the US intervention there. They might even agree that the images fed to the American public show only part of the picture. But the root of their opposition runs deeper, to political fundamentals.

|

| The point of it all – democracy |

Their critique can be summarised in the aphorism that “democracy cannot be imposed by force.” It is a view that can be found among the more sophisticated elements on the Left and, increasingly, among dissenters on the Right, from Senator Chuck Hagel of Nebraska to the ex-neoconservative Francis Fukuyama. As Senator Hagel puts it, “You cannot in my opinion just impose a democratic form of government on a country with no history and no culture and no tradition of democracy.”

I would tend to agree. But is Iraq such a place? In point of fact, before the 1958 pro-Soviet military coup d’etat that established a leftist dictatorship, Iraq did have its modest but nevertheless significant share of democratic history, culture, and tradition. The country came into being through a popular referendum held in 1921. A constitutional monarchy modelled on the United Kingdom, it had a bicameral parliament, several political parties (including the Ba’ath and the Communists), and periodic elections that led to changes of policy and government. At the time, Iraq also enjoyed the freest press in the Arab world, plus the widest space for debate and dissent in the Muslim Middle East.

To be sure, Baghdad in those days was no Westminster, and, as the 1958 coup proved, Iraqi democracy was fragile. But every serious student of contemporary Iraq knows that substantial segments of the population, from all ethnic and religious communities, had more than a taste of the modern world’s democratic aspirations. Under successor dictatorial regimes, it is true, the conviction took hold that democratic principles had no future in Iraq – a conviction that was responsible in large part for driving almost five million Iraqis, a quarter of the population, into exile between 1958 and 2003, just as the opposite conviction is attracting so many of them and their children back to Iraq today.

A related argument used to condemn Iraq’s democratic prospects is that it is an “artificial” country, one that can be held together only by a dictator. But did any nation-state fall from the heavens wholly made? All are to some extent artificial creations. The truth is that Iraq – one of the 53 founding countries of the United Nations – is older than a majority of that organisation’s current 198 member states. Within the Arab League, and setting aside Oman and Yemen, none of the 22 members is older. Two-thirds of the 122 countries regarded as democracies by Freedom House came into being after Iraq’s appearance on the map.

Critics of the democratic project in Iraq also claim that, because it is a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional state, the country is doomed to despotism, civil war, or disintegration. But the same could be said of virtually all Middle Eastern states, most of which are neither multi-ethnic nor multi-confessional. More important, all Iraqis, regardless of their ethnic, linguistic, and sectarian differences, share a sense of national identity – Uruqa (“Iraqi-ness”) – that has developed over the past eight decades. A unified, federal state may still come to grief in Iraq – history is not written in advance – but even should a divorce become inevitable at some point, a democratic Iraq would be in a better position to manage it.

What all of this demonstrates is that, contrary to received opinion, Operation Iraqi Freedom was not an attempt to impose democracy by force. Rather, it was an effort to use force to remove impediments to democratisation, primarily by deposing a tyrant who had utterly suppressed a well-established aspect of the country’s identity. It may take years before we know for certain whether or not post-liberation Iraq has definitely chosen democracy. But one thing is certain: without the use of force to remove the Ba’athist regime, the people of Iraq would not have had the opportunity even to contemplate a democratic future.

Assessing the progress of that democratic project is no simple matter. But, by any reasonable standard, Iraqis have made extraordinary strides. In a series of municipal polls and two general elections in the past three years, up to 70 percent of eligible Iraqis have voted. This new orientation is supported by more than 60 political parties and organisations, the first genuinely free-trade unions in the Arab world, a growing number of professional associations acting independently of the state, and more than 400 non-governmental organisations representing diverse segments of civil society. A new constitution, written by Iraqis representing the full spectrum of political, ethnic, and religious sensibilities was overwhelmingly approved by the electorate in a referendum last October.

Iraq’s new democratic reality is also reflected in the vocabulary of politics used at every level of society. Many new words – accountability, transparency, pluralism, dissent – have entered political discourse in Iraq for the first time. More remarkably, perhaps, all parties and personalities currently engaged in the democratic process have committed themselves to the principle that power should be sought, won, and lost only through free and fair elections.

These democratic achievements are especially impressive when set side by side with the declared aims of the enemies of the new Iraq, who have put up a determined fight against it. Since the country’s liberation, the jihadists and residual Ba’athists have killed an estimated 23,000 Iraqis, mostly civilians, in scores of random attacks and suicide operations. Indirectly, they have caused the death of thousands more, by sabotaging water and electricity services and by provoking sectarian revenge attacks.

But they have failed to translate their talent for mayhem and murder into political success. Their campaign has not succeeded in appreciably slowing down, let alone stopping, the country’s democratisation. Indeed, at each step along the way, the jihadists and Ba’athists have seen their self-declared objectives thwarted.

After the invasion, they tried at first to prevent the formation of a Governing Council, the expression of Iraq’s continued existence as a sovereign nation-state. They managed to murder several members of the Council, including its president in 2003, but failed to prevent its formation or to keep it from performing its task in the interim period. The next aim of the insurgents was to stop municipal elections. Their message was simple: candidates and voters would be killed. But, once again, they failed: thousands of men and women came forward as candidates and more than 1.5 million Iraqis voted in the localities where elections were held.

The insurgency made similar threats in the lead-up to the first general election, and the result was the same. Despite killing 36 candidates and 148 voters, they failed to derail the balloting, in which the number of voters rose to more than 8 million. Nor could the insurgency prevent the writing of the new democratic constitution, despite a campaign of assassination against its drafters. The text was ready in time and was submitted to and approved by a referendum, exactly as planned. The number of voters rose yet again, to more than 9 million.

What of relations among the Shi’ites, Sunnis, and Kurds – the focus of so much attention of late? For almost three years, the insurgency worked hard to keep the Arab Sunni community, which accounts for some 15 percent of the population, out of the political process. But that campaign collapsed when millions of Sunnis turned out to vote in the constitutional referendum and in the second general election, which saw almost 11 million Iraqis go to the polls. As I write, all political parties representing the Arab Sunni minority have joined the political process and have strong representation in the new Parliament. With the convening of that Parliament, and the nomination in April of a new prime minister and a three-man presidential council, the way is open for the formation of a broad-based government of national unity to lead Iraq over the next four years.

As for the insurgency’s effort to foment sectarian violence – a strategy first launched in earnest toward the end of 2005 – this too has run aground. The hope here was to provoke a full-scale war between the Arab Sunni minority and the Arab Shi’ites who account for some 60 percent of the population. The new strategy, like the ones previously tried, has certainly produced many deaths. But despite countless cases of sectarian killings by so-called militias, there is still no sign that the Shi’ites as a whole will acquiesce in the role assigned them by the insurgency and organise a concerted campaign of nationwide retaliation.

Finally, despite the impression created by relentlessly dire reporting in the West, the insurgency has proved unable to shut down essential government services. Hundreds of teachers and schoolchildren have been killed in incidents including the beheading of two teachers in their classrooms this April and horrific suicide attacks against school buses. But by September 2004, most schools across Iraq and virtually all universities were open and functioning. By September 2005, more than 8.5 million Iraqi children and young people were attending school or university – an all-time record in the nation’s history.

A similar story applies to Iraq’s clinics and hospitals. Between October 2003 and January 2006, more than 80 medical doctors and over 400 nurses and medical auxiliaries were murdered by the insurgents. The jihadists also raided several hospitals, killing ordinary patients in their beds. But, once again, they failed in their objectives. By January 2006, all of Iraq’s 600 state-owned hospitals and clinics were in full operation, along with dozens of new ones set up by the private sector since liberation.

Another of the insurgency’s strategic goals was to bring the Iraqi oil industry to a halt and to disrupt the export of crude. Since July 2003, Iraq’s oil infrastructure has been the target of more than 3,000 attacks and attempts at sabotage. But once more the insurgency has failed to achieve its goals. Iraq has resumed its membership in the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and has returned to world markets as a major oil exporter. According to projections, by the end of 2006 it will be producing its full OPEC quota of 2.8 million barrels a day.

The Ba’athist remnant and its jihadist allies resemble a gambler who wins a heap of chips at a roulette table only to discover that he cannot exchange them for real money at the front desk. The enemies of the new Iraq have succeeded in ruining the lives of tens of thousands of Iraqis, but over the past three years they have advanced their over-arching goals, such as they are, very little.

None of this means that the new Iraq is out of the woods. Far from it. Democratic success still requires a great deal of patience, determination, and luck. The US-led coalition, its allies, and partners have achieved most of their major political objectives, but that achievement remains under threat and could be endangered if the US, for whatever reason, should decide to snatch a defeat from the jaws of victory. The stakes, in short, could not be higher. This is all the more reason to celebrate, to build on, and to consolidate what has already been accomplished.

Is Iraq a quagmire, a disaster, a failure? Certainly not; none of the above. Of all the adjectives used by sceptics and critics to describe today’s Iraq, the only one that has a ring of truth is “messy.” Yes, the situation in Iraq today is messy. Births always are. Since when is that a reason to declare a baby unworthy of life?

![]()

Amir Taheri, formerly the executive editor of Kayhan, Iran’s largest daily newspaper, is the author of ten books and a frequent contributor to numerous publications in the Middle East and Europe. His work appears regularly in the New York Post. © Commentary magazine, all rights reserved, reprinted by permission.

Tags: Iraq