Australia/Israel Review

The Other Iraq

Apr 2, 2007 | Michael J. Totten

By Michael J. Totten

Irbil, IRAQ – What a difference a year makes. Fourteen months ago I flew to Irbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, from Beirut, Lebanon, on the dubiously named Flying Carpet Airlines. Flying Carpet’s entire fleet is one small noisy plane with propellers, cramped seats, and thin cabin pressure. Only 19 passengers joined me on that once-a-week flight. Everyone but me was a Lebanese businessman. They were paranoid of me and of each other. What kind of crazy person books a flight to Iraq, even if it is to the safe and relatively prosperous Kurdistan region? I felt completely bereft of sense going to Iraq without a gun and without any bodyguards, and it took a week for my on-again off-again twitchiness to subside.

Last week I flew to Irbil from Vienna on Austrian Airlines to work for a few weeks as a private sector consultant with my colleague Patrick Lasswell. This time I didn’t feel anything like a fool. Almost half the passengers were women. Children played on their seats and in the aisle with toys handed out by the crew. We watched an in-flight movie and ate the usual airline lunch fare served by an attractive long-legged stewardess. The cabin erupted with applause when the wheels touched down on the runway. The pilot announced the weather (sunny and 15ºC) in three languages and cheerfully told us all to have a great day. “Have a great day” may seem an odd thing to say to people who just arrived in Iraq, but this is Kurdistan. I did, indeed, have a great day.

A man named Hamid picked up Patrick and me just beyond the passport control booth. He was kindly sent by a friend on the Council of Ministers. “Here is your car,” he said as he led us to his vehicle out in the parking lot.

As he drove us into the city I felt none of the fear and apprehension I experienced the first time I came here. Instead I saw considerable signs of progress. The first time I drove from the airport into Irbil, I felt that I had arrived in a dodgy and ramshackle backwater. This time I felt – properly, I must say – that I had arrived in the capital of a serious and rising new power in the Middle East.

Nation-building is a hard and violent slog in the centre and south of Iraq, and it might not ever work out. But in Kurdistan, in the north, it already is a reality.

Massive new construction projects are literally everywhere. Most of those that had started when I arrived for the first time are finished, and ambitious new projects are well underway.

The “Dream City”, which only existed on paper when I first got here, is now partly constructed. Fancy new homes in the new city – designed on the New Urbanist model – are everywhere under construction.

The Korek Tower will be the tallest building anywhere in Iraq when it is finished. It will more resemble a tower in Dubai or the United States than anything down south in Baghdad.

Dingy and banged up road signs were replaced in the last couple of months with crisp shiny new ones. It may not seem like much, but the new signs give the city a more serious and modern look and heft.

The so-called Naza Mall recently opened to much fanfare in Irbil, and it made me wonder if the Kurds even know what a mall is. Naza Mall is a store, and it isn’t a particularly large one. But a new Western-style mall under construction next to the old souk downtown will be home for 6,000 stores and offices when it is finished.

A whole new town called “American Village” is under construction next to the luxurious Khan Zad hotel on the road between Irbil and the resort town of Salah-a-din. Foreigners and locals alike are snapping up the properties well in advance.

Iraqi Kurdistan is still a Third World country in many ways – there is no sewer system, for instance, and the electricity fails every day. Unemployment is high. But it’s a Third World country with hope, and it is rapidly moving upscale. New houses cost more in and around Irbil than they do in some parts of the United States. An average sized 200 square metre lot can cost as much as US$150,000 – and that’s before a house is built on it. There are literally thousands of brand new houses here in this city, and the population is still just a little bit shy of one million.

Arabs are moving up here from the centre and south – when they can, and as long as they are cleared by internal security – and they’re hired to do menial jobs the Kurds no longer want. Sunni Arabs were once the oppressors of Kurds. Now they are reduced to the same low status as migrant Mexican workers in the United States.

The ancient old city walls next to the city centre are an impressive sight, but inside the walls is a vast slum. Well, it was a vast slum until recently. A few months ago the residents were moved out so the city government can fix it up and restore it.

Irbil isn’t pretty, as Paris and Vienna are pretty. Some of it is aesthetically brutal, and much of it is still rough around the edges. But it’s stimulating and interesting all the same. The go-go-go and build-build-build attitude is infectious. Every time I come here it looks cleaner, and richer, and more like a normal place.

I’m less prone to boredom here than I am in Europe’s splendid capitals even though there is little in the way of entertainment culture. Irbil is the most ramshackle of Iraqi Kurdistan’s cities, but there is real raw power rising in this city and land.

The Hilton hotel chain is building a massive full-service tourist resort that will take five years to construct. It may seem dumb to build a tourist resort in Iraq of all places, but this is Irbil, not Anbar Province – there is no war, no insurgency, and no terrorism here whatsoever. The Middle East is a funny place. One part of a country may be consumed by blood, fire, and mayhem, but that rarely means the whole country is dangerous – even when that country is Iraq.

I met two old friends for dinner and embraced them both. We knew we would see each other again, but it was nice to confirm it with another actual visit. This trip is my fourth to Iraqi Kurdistan in just 14 months. A year and a half ago I could not have imagined that anywhere in Iraq would become a part of my life, let alone a pleasant part of my life. Iraq is strange, though, and more complex than it appears from far away. The civil war and the insurgency in Baghdad are real. But the civil war and the insurgency are not all there is.

“So much has changed since you were last here,” one of my friends said at dinner. “Kurdistan is a different place now.”

“What changed?” I said. Of course I had to ask, but this was a social dinner and not a formal interview. So I’ll leave their names out of this and paraphrase what they told me. Understand that they are in a position to know exactly what they are talking about.

Iraqi Kurdistan is de facto independent already. The three northernmost provinces exist as a liberal democratic state-within-a-state with its own parliament, own laws, own immigration policies, and its own military, border guards, and police. That much was already known. The region now, though, is even closer to formal sovereignty and actual independence than it recently was.

The United Nations doesn’t recognise the existence of Iraqi Kurdistan because the United Nations is hung up on state sovereignty. But the individual governments that make up the United Nations are coming around. More diplomats from all over the world are coming here now, and this is exciting to the people who live here. Foreign dignitaries who meet with local officials recognise there is a government in Iraq that isn’t in Baghdad. 99.8 percent of Iraqi Kurds voted to secede from Iraq in a non-binding referendum, and recognition of their de facto independent country is as welcome as love letters.

Both the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States have sent people here recently. One of my Kurdish dinner companions, who never wants to be quoted by name but is in a position to know, says the Democratic officials who come here support Kurdish interests as staunchly and reliably as the Republicans.

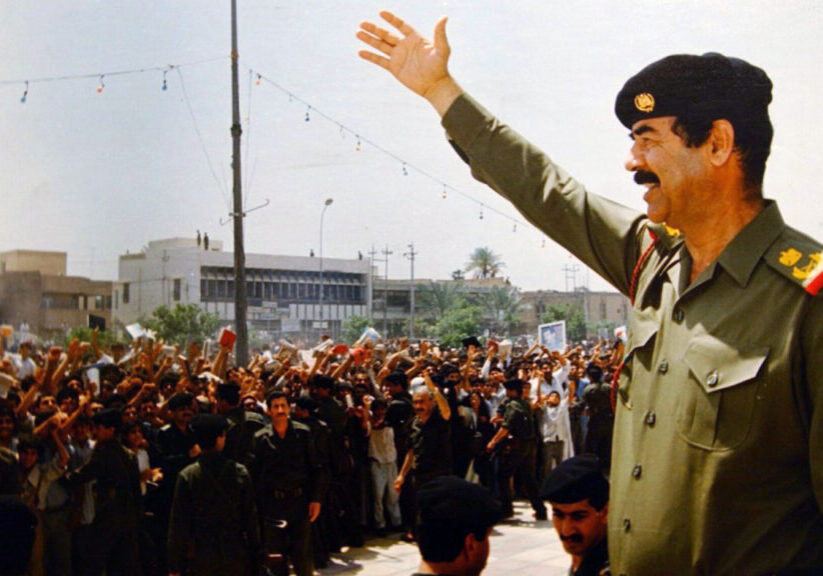

I still hear complaints about the “Kissinger Betrayal” in the 1970s, when then-Secretary of State Henry Kissinger summarily abandoned the Kurds to Saddam Hussein after promising them support for their resistance and liberation. But I don’t get the sense that too many Kurds are bracing for another round of that kind of statecraft even if the US does withdraw its forces from south and central Iraq.

Three major obstacles to independence remain. The first is Iraqi Kurdistan’s relationship with Turkey. That relationship is bad but improving despite the Turkish military’s well-publicised threats to invade northern Iraq to eject the (Turkish) Kurdistan Worker’s Party, the PKK, from using Iraqi soil to launch attacks against military and civilian targets in Turkey. Relations between the (Iraqi) Kurdistan Regional Government and the Turkish Government have quietly improved at the same time. Iraq’s Kurds genuinely want a civil relationship with Turkey because they can’t safely declare independence without it.

The Turks fear nothing more than Turkish Kurdistan declaring itself independent and attaching itself to a free Iraqi Kurdistan. A bitter civil war is still simmering in Turkey between the PKK and the Turkish state. Ethnic Kurds make up almost 25 percent of Turkey’s population. If they leave and take their land with them, the Turks will lose a huge amount of the eastern part of their country. A truly independent Kurdish state in Iraq would likely embolden Kurdish militants in Turkey – or so the Turks fear.

Iraqi Kurdistan is land-locked and surrounded on all sides by hostile people and states. It cannot survive on its own without first building a physical infrastructure that will allow it to survive border blockades as well as military invasions.

Kurdistan, unfortunately, is still connected to Iraq’s main electrical grid. And that means, as often as not, there is no power. If you want 24-hour electricity, buy a generator. And keep it topped up with fuel. (Generators are everywhere, and the large ones are louder than lawnmowers.)

Irbil Province is building a brand-new electrical grid that should work 24 hours a day and can’t be shut down by saboteurs in the Sunni Triangle or by a hostile government in Baghdad. As soon as all of Iraqi Kurdistan is electrically severed from Baghdad, the Kurds’ only remaining physical need is an oil refinery of their own.

The Kurds have enough oil. Huge new fields near Zakho were just discovered. Gasoline is expensive here, though, because oil has to be exported and then reimported.

Even without reliable electricity, Irbil is fairly well lit up at night, thanks to ubiquitous generators.

The Kurds of Iraq may not need to bother with a declaration of independence. It may fall from the sky, my source said, if the Sunni and Shi’ite Arabs break Iraq in the course of their civil war. “What would we do, decide if we want to remain with the Sunni Arabs or the Shi’a?” he said. “We don’t want to remain with either of them.”

The Kurds couldn’t stick with the Shi’ites if they wanted to. The Shi’ites and the Kurds are on the opposite side of the country, with the Sunni Arabs wedged in between from Baghdad north to the southern portions of Kirkuk and Mosul. The Sunni Arabs are the Kurds’ principal enemies, and there is no way the Kurds (who also are Sunni Muslims) will stick with the Sunni Arabs if the Shi’te Arabs decide to go their own way. If the Arabs break Iraq, as they seem hell-bent on doing, the Kurds will be freed by default. There will be no more “Iraq” for them to stay shackled to.

In the meantime, the Kurds are doing their best to cultivate civil relations with the Sunni Arabs while digging a massive trench on the Green Line to keep the insurgents, the car-bombers, and the suicide-bombers out. The trench is more like a castle moat, really. It’s five metres wide, five metres deep, and it drops straight down. Anyone trying to cross it without building a bridge will find themselves in a free fall. It’s an inverted version of the barrier that separates Israelis from Palestinians. Walls and trenches can be still be crossed, to be sure, but they can’t be crossed quickly, and they certainly cannot be crossed with any vehicles.

My dinner companions were shocked when I told them I’m going to Baghdad next month with the American military. (I’m going, that is, unless the Department of Defence delays my trip yet again.) “Are you sure you want to go down there?” one of them said. “The Sunni militias cut throats and the Shi’ite militias drill holes in people’s heads. That’s Baghdad.”

Recently some terrorists from one of the militias dumped three dead bodies on a street and broadcast an announcement for the neighbours: Anyone who tries to bury one of the bodies will join them. For three weeks everyone walked past decomposing corpses as dogs tore at and ate the flesh. Innocent children who do not yet understand the cruel ways of their terrible city asked their parents why those people were sleeping so long in the street.

Kurdistan is safe even without its anti-terrorist trench, and that’s not because it is protected by American soldiers. Only 50 or so troops remain in this part of Iraq. There is no anti-American insurgency (because there is virtually no anti-Americanism) and there is no terrorism. If the Arab Iraqis were as peaceable as the Kurds, the American military could have folded its tents a long time ago.

Iraqi Kurdistan is technically occupied by a foreign power, but this occupation surely ranks among one of the most absurd in human history. Dr. Ali Sindi, adviser to Prime Minister Nechervan Barzani, told me that South Korea is the official occupier of “Northern Iraq”. Korean soldiers are stationed just outside Irbil in a base near the airport. He laughed when he told me the Kurdish military, the Peshmerga (“those who face death”), surround the South Koreans to make sure they’re safe.

Every couple of weeks another government somewhere in the world drops their travel advisory for Iraqi Kurdistan. The regional government sends me an email every time it happens. It is always seen as yet another milestone passed on the road to independence from Baghdad. Not only is Kurdistan recognised as separate from Iraq, it is also recognised as different from Iraq. Iraq is dangerous, but the north really isn’t.

Kurdistan’s rise flips Iraq on its head. The Kurds are ahead, but they started from nothing. Under Saddam’s regime they had the worst of everything – the worst poverty, the worst underdevelopment, and worst of all they bore the brunt of the worst violence from Baghdad. Two hundred thousand people were killed (out of less than four million) and 95 percent of the villages were completely destroyed.

The Kurds seem happy and well-adjusted. Scratch the surface, though, and any one of them can tell you tales that make you tremble and shudder. Everyone here was touched by the Baath and by the genocide. If living well is the best revenge, the Kurds have got theirs.

“You see this place now with its government, its democracy, and its system of laws,” my guide Hamid said. “It wasn’t like this even recently, believe me. Before, it was a jungle.”

Baghdad, the Sunni Triangle, and the Shi’ite south are still jungles. No one I know here thinks the Sunni and Shi’ite Arabs will be able to reconcile and live with each other in peace – there is too much bad blood between them. I don’t know if that’s true or if it’s not. The Middle East is an unpredictable place, and I’ve made a fool of myself often enough by thinking I know what will happen.

What I do know for sure is that Baghdad is burning and Kurdish power is rising. The question up north isn’t whether Iraq will come apart, but only when, how, and into how many pieces.

![]()

Michael J. Totten is freelance journalist and blogger (ww.michaeltotten.com) based in Beirut, Lebanon. His work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Bulletin, LA Weekly, and Beirut’s Daily Star, among other publications. © Michael Totten, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iraq