Australia/Israel Review

The Biblio File: Rogues States and Diplomatic Dreams

Jun 30, 2014 | Tzvi Fleischer

Tzvi Fleischer

Dancing with the Devil: The Perils of Engaging Rogue Regimes

Michael Rubin, Encounter Books, 384 pages, £16.65

North Korea. Iran. The Taliban. Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Pakistan. Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya. The PLO, Hamas and Hezbollah.

These rogue states, regimes and groups have been the stuff of geopolitical nightmares over the past 40 years. But as Michael Rubin demonstrates in his important new book, Dancing with the Devil: The Perils of Engaging Rogue Regimes, they are also the stuff of diplomatic dreams.

Dreams that “engagement” will lead to a breakthrough, that diplomacy will turn rogues into responsible international citizens, even partners. Dreams that actors who are adversaries can come to see that they share common interests, thus reducing the risk or reality of violence. Dreams that politicians will reap the political benefits of a breakthrough, that the diplomats involved will turbo-charge their careers by crafting an understanding that will bring a rogue actor to heel.

Yet as Rubin shows, these dreams almost never come true. Moreover, while advocates of engagement almost always argue that diplomacy costs nothing and it is always better to be talking than not talking, Rubin demonstrates that this is often simply wrong. The diplomatic dream of engagement frequently involves significant costs and little benefit. In a series of case studies, Rubin illustrates these costs across a whole series of American efforts to engage with seven different rogue actors over the past four decades, through eight different US Administrations.

The North Korea chapter constitutes the most classic example – a case where repeated efforts to engage over four decades simply provided Pyongyang with opportunity after opportunity to gain huge benefits – billions in monetary aid, essential fuel oil, international willingness to ignore or tolerate behaviour that otherwise might have led to counter-measures, and leverage to keep the bonanza coming. As Rubin writes:

Pyongyang’s playbook never changed: First, they provoke, then they consent to accept an agreement in exchange for concessions, and finally they violate the agreement and the whole things starts again.

Rubin demonstrates that this simple strategy worked like a charm again and again, with no US administration learning from this pattern of behaviour which dominated the experience of all its predecessors.

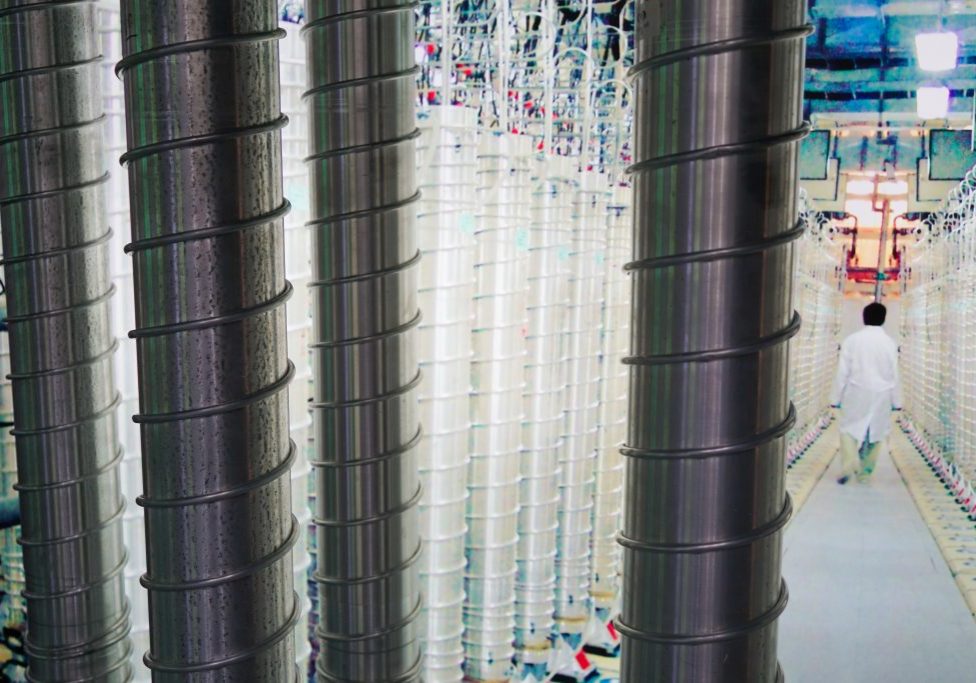

Aside from North Korea, the case with the most contemporary resonance is Iran, where Rubin demonstrates that, contrary to claims often heard in the media, US efforts to engage have been almost constant since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. And while the pattern is not as starkly obvious as in the Korean example, it is repeatedly made evident that Iranian leaders viewed the relationship in zero-sum terms and negotiations as an opportunity to exploit to paralyse and confuse the enemy and gain an advantage. And there is also a repeating pattern of US negotiators and leaders refusing to accept evidence of Iranian duplicity.

Other cases strongly establish that the book’s core thesis – the falseness of the belief that negotiation and engagement are cost free – is amply supported by the US experience with rogue states over recent decades.

If the book has a shortcoming, it might have been enhanced by an attempt to more systematically summarise the numerous ways in which efforts to engage rogue states have proven costly – perhaps in a list or table.

However, one lesson that does come out in case after case is that the hope that engagement will strengthen moderate forces in the rogue state and create interest groups there devoted to perpetuating the negotiating process actually works in reverse. It is democracies which engage with rogues that end up with a strong constituency, in government and outside, ready to insist that almost any cost is worth paying to keep dialogue going, and to blame the failure to achieve a breakthrough on their own government’s mistakes.

The book stresses repeatedly that diplomats could greatly increase their learning from experience if they made an effort to systematically conduct a detailed and forensic post-mortem after each diplomatic series of encounters – as is routine in the military.

This is a book that any statesman or diplomat confronting a rogue regime should read. Diplomacy, properly employed, remains of course essential to dealing with rogues – but the key is to develop the ability to distinguish between counter-productive and costly efforts to engage built on nothing but hopes and dreams and real diplomatic opportunities built on a base of genuine political leverage.

Tags: International Security