Australia/Israel Review

Opportunity Knocking

Aug 1, 2007 | Amotz Asa-El

Bush’s latest Middle East initiative

By Amotz Asa-El

|

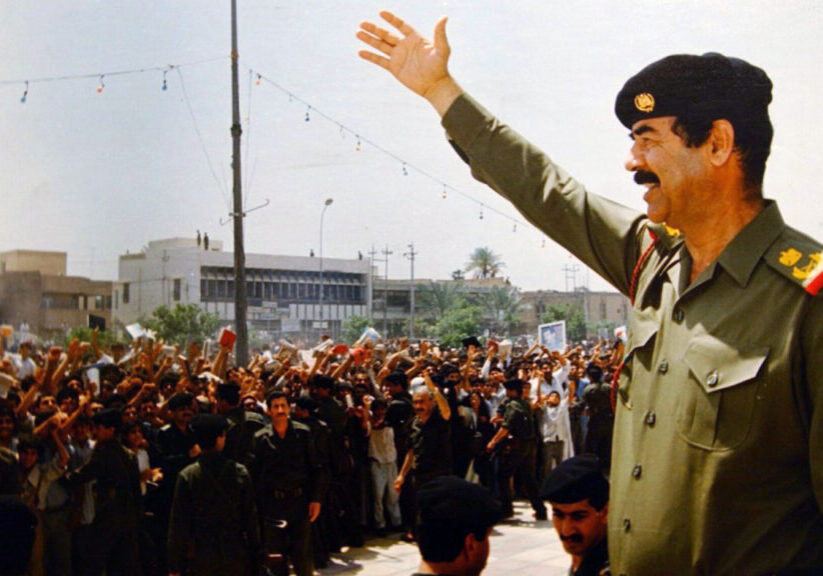

| Bush: Adjusting his vision to the region’s shifting sands |

Five years after unveiling an ambitious vision for a reinvented Middle East, US President George Bush has adjusted his game plan to the region’s rapidly shifting sands.

What began as a proactive post-9/11 ambition to democratise the entire Arab world was now being tested by Gaza’s downfall to Hamas, and giving way to a defensive strategy, lest the Islamists march on – to the West Bank.

Ideologically, Bush’s address in the White House last month was consistent with his landmark address to Congress in June ’02, as both speeches hailed freedom, tolerance and Palestinian statehood, and neither accepted the common dictum that the Middle East’s troubles begin and end in Arab-Israeli disharmony. Similarly, Bush’s main innovation – an international conference on the Middle East to be held this northern autumn – was no more novel in Middle Eastern peacemaking history than were his introduction of a new peace envoy or his release of more funds for the PA.

It’s not that the envoy, Tony Blair, brings to the role more stature than his many predecessors, nor is it that Bush was handing Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas a fresh US$190 million, nor even that Israel was handing him 255 prisoners as well as further funds. Rather, it is that Bush was effectively telling the Palestinian people that this may well be their last chance to accomplish the independence for which they have been fighting since the 1930s.

The general setting could hardly be grimmer. Not only has fundamentalism snatched Gaza, but the week after Bush’s speech Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Hezbollah leader Hasan Nasrallah showed up in Damascus, where President Bashar Assad reportedly agreed to shun Bush’s initiative in return for a US$1 billion Iranian arms deal. One can hardly think of a more stinging get-together from Washington’s viewpoint, in Damascus of all places, and so soon after Bush’s much-heralded announcement.

Bush’s demands that the Palestinians abandon fanaticism and violence may therefore have sounded old and even banal, but beyond them lurked an attitude. Referring to Hamas’ brutal overthrow of Fatah from Gaza in June, and to the Strip’s consequent severance from the West Bank, Bush said the Palestinians had arrived at “a moment of clarity,” which is now being followed by “a moment of choice.” To choose statehood, he said, the Palestinians “must decide they want a future of decency and hope, not a future of terror and death.” And what if they ignored his advice, as they have in the past? Apparently, they will then have to forget about attentive ears in the US.

|

| Blair’s role will be to try to fashion a mercantile, outward-directed West Bank |

Bush’s message was aimed not primarily at the fundamentalist Hamas, whose violent conquest of Gaza has obviously provoked Washington, but also to the secularist Palestinian Authority, whose well-equipped troops’ failure to fight was no less alarming. “Decency and hope”, it turns out, was a euphemism for political maturity, an attitude that would entail dealing less with what the Palestinians demand of others, and more with what they are prepared to demand of themselves.

In this vein, Bush parted with the longstanding American insistence that the Palestinian economy be intertwined with Israel’s.

Echoing the thinking with which Israel’s former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon unilaterally disengaged from Gaza two years ago, Bush said Palestinian exports had best be sent abroad not through Israeli ports, but through Egypt and Jordan. This idea resembles the common Israeli view of recent years – that rather than full peace, all that could for now be sought with the Palestinians is a kind of non-belligerency. The idea is that each society would develop on its own on opposite sides of diplomatic cleavages, administrative partitions, and even physical walls – in addition to the emotional ones that, following this decade’s violence, have arguably risen taller than ever before.

In terms of labour markets, this disengagement has long been a reality. With Israeli employers reluctant to employ potential terrorists, and with globalisation supplying unskilled labour amply, quickly and cheaply from other sources, the Palestinian share in Israeli labour has dwindled over the past two decades. It has plunged from more than 100,000 to fewer than 20,000, over a period during which Israel’s population has grown by about one third, and the Israeli economy more than doubled.

In the new American thinking, Israel will of course be expected to at least passively support the emergence of a Palestinian economy, but the Palestinians’ test will be in their willingness to fashion the West Bank as a mercantile and outward-directed antithesis to a feudal and obscurantist Gaza. Israel’s role will be to ease financial inflows into the West Bank and traffic within it, by removing some of the roadblocks that have helped thwart terror attacks, and by halting expansion of West Bank settlements.

Meanwhile, the Hashemite Kingdom will be expected to intensify its links with the West Bank, in line with newly elected Israeli President Shimon Peres’ old vision of economic fusion across the Jordan River.

This is the backdrop against which Salam Fayyad, a pragmatic, American-educated economist untainted by terror or corruption, but also shorn of a political base, has now been appointed prime minister, while retaining his previous position as treasurer. The American hope is that Fayyad will use the new foreign aid to create non-governmental jobs – in contrast with the elaborate public sector Yasser Arafat created with the massive aid he received after signing the Oslo Accords.

To Washington, Fayyad and Abbas embody the quest for a pragmatic Palestinian Authority that will shun violence, appreciate prosperity, educate for tolerance and nurture social mobility. What they mean for the average Palestinian is a separate question, and the answer may arrive soon through an early election which Abbas has said he will decree imminently, for both parliament and the presidency.

Such a move will be a logistical challenge, as Hamas, which has already responded harshly to the idea, can be expected to make it difficult even to cast ballots in Gaza, let alone allow the people to vote freely and have their votes counted fairly. For now, it seems the Palestinians are in for more internecine strife and that the abyss that has come to yawn between Gaza and the West Bank is not likely to be bridged anytime soon.

Moreover, even if an early election is somehow conducted flawlessly, and even if its results are positive from the American point of view, a diplomatic breakthrough may still prove elusive – for the prosaic reason that to endure, any resolution must have support beyond the Palestinian arena.

That is why Bush is convening a regional conference.

As of late July, details about the conclave remained unclear (other than that the conference will be chaired by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice), from its time and location to its agenda and participants.

The idea of a Middle East peace conference harks back to the 1970s, when many in the international community hoped that such a venue would produce joint American-Soviet pressure that would make Israel cede land and its enemies accept the Jewish State. Within Israel this idea later became a bone of contention between Right and Left, as the former saw in it a plot to force Israel to concede land. Still, in ’91, an international conference was convened in Madrid by George H. W. Bush while Israel was actually led by its most right-wing prime minister ever, Yitzhak Shamir.

Now things are simpler for Israel.

First, in ‘91 the conference was attended among others by some of Israel’s most implacable enemies, including Syria, which was not asked to do what Bush now demands, namely that all conferees abandon “the fiction that Israel does not exist,” stop inciting against Israel, and normalise ties with it.

For its part, Israel’s political centre of gravity has moved enormously since 1991. Its current leadership responded to the Bush initiative warmly. For Prime Minister Ehud Olmert the conference will in fact be a major success if it includes Saudi representatives, as Riyadh has yet to recognise Israel. At the same time, few in Israel expect the conference to generate even such a limited achievement, let alone anything grander, such as a broader Arab recognition of Israel, or the basis for fully fledged peace accords.

The Saudis have so far offered few indications concerning their attitude toward the dilemma Bush has handed them; if they shun the conference, they will embarrass their main ally, and if they join, they will anger fundamentalists both within and beyond the Arabian Desert.

The Bush initiative is problematic also for the rest of Washington’s Arab allies.

For Egypt, Gaza’s isolation is a problem since Cairo fears such a fundamentalist pocket’s radiation into Egypt; for Jordan, the idea of reconnecting the West Bank to the East Bank is also problematic, as King Abdullah is suspicious of his own Palestinian population, which comprises over half his kingdom’s citizenry.

For Bush, at the same time, this is apparently a last attempt to untie the Middle Eastern Gordian Knot that, from 9/11 through the war on Iraq to the latest crisis in the Palestinian areas, has dominated his presidency.

Curiously enough, Bush’s initiative comes as he and his main partners in the conference, Olmert and Abbas, suffer from severe image problems. A successful conference, one that truly generates a sense of diplomatic breakthrough and economic momentum – say by declaring a timetable for agreements on the establishment of a Palestinian state as well as a slew of multi-billion dollar mega-projects – does not seem likely. The conference should be seen as a success if it consolidates the so-called Sunni axis and the West Bank’s status as Islamist Gaza’s counterbalance.

Then again, the anti-American summit in Damascus may have been less about bravado, and more about alarm – alarm in the face of a stubborn Texan president’s insistence on trying to redefine the Middle East in a way no-one has since the end of the colonial era. And if Syria, Iran and Hezbollah are not ruling out the prospect of a successful US-brokered regional diplomatic breakthrough, neither should everyone else.

![]()

Tags: Iraq