Australia/Israel Review

Misunderstanding Assad

Apr 18, 2011 | Tony Badran

By Tony Badran

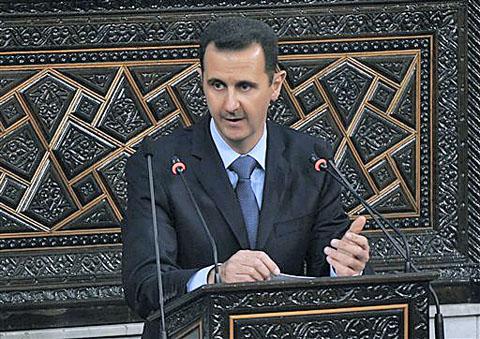

Understanding the behaviour and decision-making of the Syrian regime has long eluded policymakers and analysts. A year ago, one US official lamented this inability to comprehend why Syrian President Bashar al-Assad behaves the way he does, dubbing it “the million-dollar question.”

The ongoing upheaval in Syria has once again placed this problem under the spotlight, as observers struggle to make sense of the regime’s domestic policies, having equally failed to grasp the rationale behind its regional posture. In fact, the misunderstanding of the regime’s foreign policy is directly linked to the incomprehension of its internal stance.

Accompanying Assad’s response to the popular demonstrations against his rule has been the expert and journalistic commentary that ostensibly set out to explain the Syrian president’s actions. Instead, the analysis has been a mixture of befuddlement and specious arguments, highlighting why general understanding of the Assad regime’s behaviour has been so lacking.

While Assad’s aides issued vague pronouncements to the media, the coterie of professional Syria watchers wrung their hands waiting to hear how Assad himself would respond to the protesters’ demands. Leading the pack was self-styled Assad confidant, academic David Lesch, who penned a concerned op-ed in the New York Times, which he led with the distressed question: “Where has President Bashar al-Assad … been this week?” “He has to LEAD,” he emphatically cried elsewhere.

When the Syrian president finally addressed the situation in a speech before parliament, the experts expressed their deep disappointment with and shock at its dismissive style and substance. Moreover, concomitant with his smug speech was Assad’s continuing brutal crackdown on the peaceful demonstrators.

The simultaneous hints about promises of potential reform, along with the use of violence and rejectionist rhetoric, perplexed analysts, leading one of them, academic Joshua Landis, to conclude that the regime’s posture “shows there is real confusion in the government” on how to deal with the situation. Lesch expressed similar views.

However, this argument fails to recognise that the regime’s domestic response is the mirror image of its standard pattern of behaviour in its foreign policy. There too analysts and policymakers have grappled with the regime’s position, attempting to reconcile its alleged desire for “peace” with its unrelenting support for and use of violence.

But this decades-long approach hardly reflects “confusion” on the part of the Assad regime. Rather, it is clearly a calculated strategy, and one that has served the regime well for decades, as evident from the infamous legacy of the peace process. In fact, it is so premeditated that Assad has even coined a catchy little line to express it: “Peace and resistance form a single axis.”

Most analysts, especially those whose worldview is filtered through the peace process, continue to misinterpret that maxim and its repercussions. And the fallacies that hinder a sober assessment of Assad’s foreign policy similarly muddle domestic policy analysis.

For instance, Syria experts typically try to resolve the apparent paradox of Syria’s foreign policy posture by positing speculative and unverifiable divisions in the decision-making circles between supposed “hardliners” and “pragmatic reformers” representing an alleged “peace camp” that longs to be allied with the West. For years, some even questioned whether Assad was actually in control of Syria, just as today some are wondering whether the violence against protesters is the work of “rogue” security apparatuses. After all, Assad’s top aide told the press that the President had specifically ordered that no Syrian blood be shed!

These starry-eyed, bewildered justifications of the regime’s current response are due to the fact that the majority of observers hold the belief that Assad is indeed a “reformer.” Seen through this lens, Assad’s actions would indeed appear baffling. Why wouldn’t this “reformist” President simply reform? This question drove the analysts to speculate feverishly about hypothetical centres of power that may have prevented him from acting on his repressed reformist impulse. In its more laughable forms, this line of thinking led some analysts to “advise” Assad to “split” with his own regime.

The common denominator here is the analysts’ penchant to insulate Assad and justify his actions, always preferring to give him a pass, so as not to cause the collapse of their own intellectual house of cards. Needless to say, Assad dispelled this nonsense in his speech, specifically ridiculing how Westerners always relay their concerns to him about the negative impact of his entourage on the “reform” process.

But analysts chose to ignore that part of the speech, preferring to stick to their own categories and misconceptions, much to Assad’s delight. After all, Assad’s peculiar genius is in sitting back and letting his Western interpreters read whatever they wished into his intentions regarding peace and the relationship with the US, especially as it didn’t imply any actual commitment on his part. Meanwhile, for anyone who bothers to look closely, Assad has been rather clear that his conceptions and those of his interlocutors or of the analysts are two wildly different things.

In brief, it should now be crystal clear that the prevailing analytical paradigm is deeply flawed. This is precisely what led that anonymous US official last year to bemoan how not only does the Obama Administration “not understand Syrian intentions,” but, in fact, “[n]o one does, and until we get to that question we can never get to the root of the problem.”

In reality, the Assad regime’s behaviour and intentions are not at all perplexing, but are rather plain to see. However, that requires identifying the patterns and methods this regime has employed for decades.

Tony Badran is a research fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington. This article was first published on NOW Lebanon. Reprinted by permission of the author, all rights reserved.

Tags: Syria