Australia/Israel Review

Lebanon’s Curse

Sep 1, 2020 | Danielle Pletka

It is almost as if Lebanon is cursed. The horrifying explosion at the city’s port on Aug. 4 seems a cosmic slap in the face, a blow when the country is at its lowest. The Prime Minister has quit; ditto the rest of his cabinet. The Lebanese Pound has lost 60% of its value in the last 10 months (and 80% of its black market value). The International Monetary Fund is refusing to lend the COVID-stricken economy much-needed cash because of corruption.

The country is ruled, in a de facto fashion, by the terrorist group Hezbollah, which, apart from its manifest faults, is now also being pressed by Iran to attack Israel. And that’s just this year. Years past whipsawed the Lebanese from civil war to war with Israel, terrorism and kidnapping, to Syrian and Iranian vassal state.

But what this narrative leaves unstated is that much of Lebanon’s fate is its own making, or at the very least, the making of an irretrievably corrupt elite, tolerated – and too often abetted – by a population that knows no other form of governance. The Beirut port tragedy is only the latest display of staggering corruption and incompetence. Was gross negligence behind the port disaster? Or was it a Hezbollah bomb supply depot?

The world will likely never know, as Hezbollah is resisting an international inquiry. But it is almost certain that this tragedy, like the many before it, is the product of the corruption, venality and incompetence that has brought the “Paris of the Middle East” to its knees. Indeed, at every twist in Lebanon’s fate, there has been a seemingly inexhaustible supply of feckless leaders and the various foreign despots to whom they have turned for favour. All have conspired to destroy the nation.

Gauzy memories of the halcyon years before Lebanon’s civil war broke out in 1975 are mostly false, but the decades that followed were certainly worse. In theory, the national pact of 1943 that divided the spoils of leadership among Lebanon’s Christian, Sunni and Shi’ite populations might have sustained a unique experiment in sectarian and religious harmony in the Middle East. In reality, it cemented into place the patronage and corruption that have reached their apex in 21st century Lebanon.

Quibbles over leadership and rank mismanagement of Lebanon’s growing Palestinian refugee population – and the attendant Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) terrorists that treated the nation as their own – led first to the creation of militias intended to suppress the proliferation of Palestinian militias; and then to the fateful moment when the then-president invited in the Syrians to keep the peace.

In a Faustian bargain, the likes of which Goethe could not have imagined, the nation was to become a playground for Syrian dictator Hafez al-Assad, his terrorist proteges, and his Iranian patrons.

Few remember the proliferation of Palestinian terror groups that targeted Jews and Israel, and bickered among themselves, through the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. The PLO was but the largest and best recognised. There was also the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine; a disgruntled offshoot, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command; the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and others whose names have faded over the years. Each treated Lebanon as an arms depot, its teeming Palestinian refugee camps as operational headquarters, its airport as a private airfield for terrorist adventurism.

In those years, alliances shifted with lightning rapidity. Christians begged at Assad’s feet, and when he proved useless, at Israel’s. Others begged world powers for favour, but the Marine barracks bombing of 1983 and a succession of terrorist attacks on US facilities and on Americans drove all but the most mercenary away.

Lebanese Christians fled in droves, taking their businesses, their assets, and their families. So too did the Palestinian managerial cadres that had shared generous remittances with their families trapped in Lebanon. But at no moment – not a one – did the various Lebanese factions that promised a better future to their followers abandon the civil war model: foreign patrons, foreign allegiance, and corruption.

Presidents were murdered; prime ministers too. But even the murder of Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in 2005 – for which Syria and Hezbollah were almost certainly responsible – gave little respite to tiny Lebanon.

Yes, Hariri’s brutal assassination ended the direct Syrian occupation of Lebanon, but by that point the physical presence of those troops no longer mattered, for two important reasons. The first was that everyone who could have been influenced, bought or sold had already been, and it did not take Syrian strongmen on the ground to keep them in line. The second was that the civil war had bred its most disastrous spawn, which would make the Syrian occupation look tame in comparison: Hezbollah.

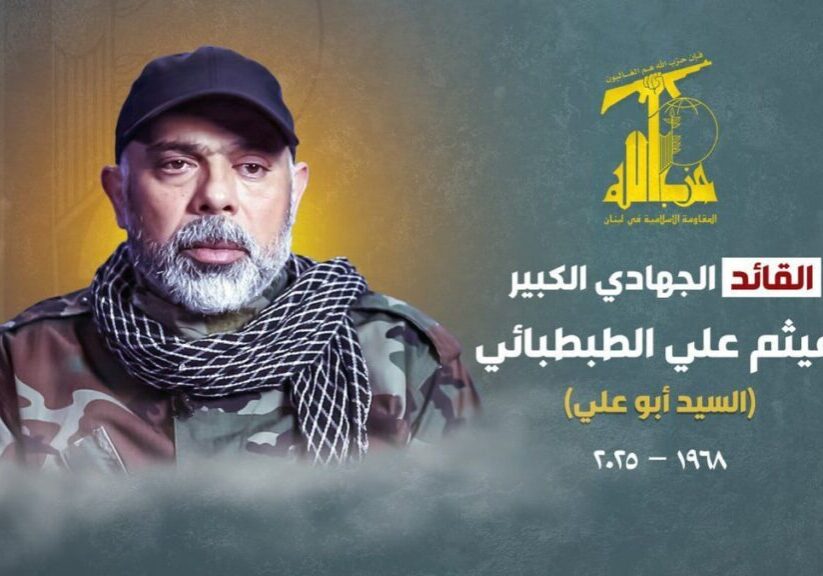

A creature of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, Hezbollah grew in the 1990s and has since taken over Lebanon lock, stock and barrel. It answers to Iran, it fights for Bashar al-Assad in Syria, it governs in Beirut, and it dominates everyone and everything in Lebanon.

It is as if all the worst crimes of Lebanese leaders were concentrated in the person of Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s leader, and his minions. They are corrupt. They are sectarian. They kill on command, attack Israel on command, and oppress their internal foes as if the civil war were still at its height. The people of Lebanon they nominally represent have never been anything other than an afterthought.

Of course, Lebanon has mundane problems of corruption as well: the Central Bank arbitraging lending rates to benefit a few cronies; the President and his family and friends manipulating electricity prices; and the petty cronyism of every third world state with byzantine trappings that might be funny were they not so sad.

There are close to 500,000 civil servants supping at the government trough (in a country with a population of 6.8 million), their costs sucking up a third of the state’s budget. The state railway office has dozens of staff, though not a single train has plied the nation’s rails in decades. Bribery is not just widespread, it is ubiquitous: Just shy of 100% of companies report they had to pay bribes to secure government contracts, and more than a third of the nation’s citizens have reported bribes to police.

Is all this obvious to the people of Lebanon? You bet. Does it outrage the crowds that teemed in Beirut’s streets last year, and returned once COVID fears settled? Sure. Is their anger all the more intense now that much of their capital has been destroyed? Obviously. Will they throw the bums out? They’ll try. But there will just be other bums.

In a dream world, it might be possible for a technocratic government to be swept in with the shockwave that levelled Beirut on Aug. 4. In a parallel dream, perhaps the state could again become a French protectorate, as some have asked. In fact, what will happen is that conspiracies will abound about the port blast; and money the international community gathers to repair this latest wound will be stolen, as so much has been stolen before.

There will be no peace because those who have power in Lebanon – Iran, Hezbollah and the shadowy thieves who run the government – will not relinquish their power or their ill-gotten gains. And eventually, another tragedy elsewhere in the world will catch our eye and Lebanon will be forgotten.