Australia/Israel Review

Killer Questions

Feb 1, 2008 | Peter Bergen

Who murdered Benazir Bhutto?

By Peter Bergen

The last time I saw Benazir Bhutto was over dinner at the Willard Hotel in Washington, DC, three weeks before her October 2007 return to Pakistan. She was in enormously good spirits, almost effervescent. The years in the political wilderness looked like they were coming to an end. But, at one point, the conversation took a more serious turn as she began discussing the mysterious death of General Zia, the Pakistani dictator who had hanged her father in 1979.

Zia died in a plane accident in Pakistan nine years later. What was especially strange about the crash was that there was no Mayday call from the pilot; the plane just dropped out of the sky, killing everyone on board. Bhutto had followed the case closely, and she advanced the theory that a box of mangos, delivered onto the plane at the last minute, secreted a canister full of poisonous gas that disabled the pilots.

Two decades later, who exactly and what exactly killed Zia is still a mystery. It is not surprising, perhaps, that Bhutto’s own death seems cloaked in a similar shroud of conspiracy and mystery. This is the Pakistani way.

I boarded a plane for Karachi on Dec. 27, the day Bhutto was killed. When I arrived, the streets of this usually throbbing megalopolis of 14 million were deserted, stores shuttered, gas stations closed, food supplies running low and Army Rangers posted at important intersections. To control the rioting, the soldiers had shoot-to-kill orders. Occasionally, I heard shots in the distance.

The day before, Bhutto’s enemies – for the second time since she ended her exile two months before – had attacked, this time deploying a gunman and suicide bomber to finish the job. Immediately, reality became murky. The government fingered as the mastermind Baitullah Mahsud, the head of the Pakistani Taliban and an all-too-plausible candidate. Bhutto’s party, the Pakistani People’s Party (PPP), denounced this claim, saying he was a patsy designed to take the heat off the government for failing to provide sufficient protection for their leader. Bhutto’s husband, Asif Ali Zardari, even hinted that Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf himself had a role in the attack, referring to Musharraf’s political party as “the Killer League.” Zardari also said that a dossier compiled by the PPP about alleged vote-rigging by the government, which his wife planned to hand over to US Senator Arlen Specter and Representative Patrick Kennedy the day she died, might have been a motive.

Obviously, it was going to be hard to find information in the States about what, and who, had really killed Bhutto. I hoped, in coming to Pakistan, to find more answers.

It seems surreal that the first part of that mystery – what actually caused her death – should be so hard to solve. But it may be one thing we never definitively know. What we do know is this: Four days after two suicide bombers tried to kill her in October, Bhutto met with US Embassy staff asking for protection. The following day, a Western official specialising in security met with the PPP leader to tell her that having Americans on her security detail would make her an even bigger target; he suggested that she hire a local security firm instead and provided a list of the three best firms in Pakistan.

Bhutto wasn’t convinced. The only people she trusted were PPP members, and as a result, according to a Western diplomat, her security was arranged by “her boys”, armed party workers from the PPP, not by a professional outfit like Wackenhut, a US security firm operating prominently in Pakistan. A longtime confidant of Bhutto’s told me that the PPP was suspicious of Wackenhut because it employs many Pakistanis; Bhutto wanted a security firm staffed by foreigners. But, for that, the PPP needed permission from the Interior Ministry, which the confidant says was never given.

It is that fact that has shaded all hypotheses about what in fact killed Bhutto. In the minutes before she was killed, she was standing up through the sunroof of her armoured vehicle – a sunroof that she’d had installed and that she used despite the pleas of many others. A videotape of the attack shows a clean-shaven young man, wearing a dark jacket, tie, and rimless black shades, stepping toward the vehicle. Behind him stands a tall man whose face is wrapped in a white headscarf. He is presumed to be the bomb carrier, his bulky clothing disguising a suicide vest packed with explosives and nails. Using only one hand, the gunman, who later died in the attack, shoots three times in Bhutto’s direction. Bhutto’s back is toward the camera. Her headscarf billows slightly, she starts to drop inside the vehicle; then the bomb goes off and the screen goes black.

To hit even a slowly moving target with a gun one-handed in the middle of a boisterous crowd requires considerable skill, and the government asserted that the cause of Bhutto’s death was a head injury sustained when she fell (or was pushed by the bomb blast) during the attack and hit her head on the lever of the sun roof. The government’s explanation seemed designed to undercut her martyrdom. It also attempted to render moot claims by PPP officials that, if the government had cooperated, they would have been able to provide Bhutto with proper protection.

The PPP has angrily dismissed the assertion that she died from a head injury, but the physical evidence tends to support the government’s explanation. The medical report filed by seven doctors who treated Bhutto in the hospital says she died as the result of a skull fracture and head injury. No exit wound or bullet fragments were discovered during their examination. However, no autopsy was performed: Bhutto’s family members – who have reason to be distrustful of the government – refused the procedure, which, in any case, Muslims regard as a desecration. And, without an autopsy, a definitive cause of death cannot be determined.

But, whether Bhutto was killed by gunshot or a head injury, the videos of her killing show that she was not being protected by professional bodyguards who would have moved to block her after the first shot was fired. The Western official specialising in security told me, “They were amateurs.” Professionals would have yelled “Gun!” as the shooter first drew his weapon and would have shot him immediately.

If what killed Bhutto may remain a mystery, the question of who had her killed – by far the more important question – needs to be answered. Some Pakistanis, notoriously prone to conspiracy theories because their country’s history is so rich with conspiracies, have pointed the finger at Musharraf or the country’s military intelligence agencies. Hillary Clinton herself speculated that the hit might have been an “inside job.” But it’s obvious that Musharraf – already one of the least popular figures in the country – had nothing to gain from Bhutto’s death: He has lost whatever shreds of popularity he had left since the assassination. Nor is it likely that senior military commanders, who have a strong interest in maintaining Pakistan’s stability, would be involved.

Others have suggested lower-level military involvement or the participation of rogue elements in the intelligence agencies in the Bhutto hit, which took place in Rawalpindi, where the headquarters of Pakistan’s military are located. And, indeed, two assassination attempts against Musharraf in Dec. 2003 that also took place in Rawalpindi provide a model of how that might have happened. In the first, low-ranking Pakistani Air Force personnel launched a bomb attack on Musharraf’s convoy. In the second, carried out by two suicide bombers, members of Pakistan’s elite commando Special Services Group conspired to kill him.

But that’s not the whole story. According to American officials and Musharraf’s 2007 autobiography In the Line of Fire, while military personnel were integrated into the plots, both assassination attempts were in fact masterminded by al-Qaeda. And these attacks came three months after al-Qaeda’s number two, Ayman al-Zawahiri, had for the first time issued a tape specifically calling for attacks on Musharraf.

Al-Qaeda and its affiliated groups have long harboured an antipathy for Bhutto.

On a dank, freezing day in March 2000, I met with the PPP leader at the home of a supporter in suburban New Jersey. At the time, she was living in exile in London and Dubai, beset by corruption charges and something of a pariah in official Washington. She seemed defensive, going into lengthy monologues about her enemies inside Pakistan’s national security establishment and delivering Talmudic exegeses of the corruption cases against her.

I was interviewing her for a book about al-Qaeda. She surprised me with a story about a young Saudi militant based in Pakistan who bribed some parliamentarians to vote against her in a no-confidence vote during her first term as prime minister, in 1989. His name was Osama bin Laden.

When she told me that story, bin Laden had not yet attained global infamy, and it is entirely credible that the Saudi militant, who had founded al-Qaeda in the Pakistani city of Peshawar in 1988, would have done anything to sabotage the Western-oriented female leader who had just replaced the pro-Islamist military dictator General Zia. As Bhutto explained to me, “The international Islamist movement saw Pakistan as its base. They saw my party as a liberal threat.”

In February 1993, an al-Qaeda-trained militant named Ramzi Yousef masterminded the bombing of the World Trade Centre, killing six. He left Manhattan the day of the attack, heading for Pakistan. Almost immediately, he began plotting to kill Bhutto, then serving her second term as prime minister. The plan was aborted when the bomb Yousef was building malfunctioned, causing him an eye injury for which he was admitted to a Karachi hospital.

Recently, Robert Novak wrote a column containing the bizarre assertion that neither of the attacks against Bhutto “bore the trademarks of al-Qaeda.” But the use of multiple suicide attackers is an al-Qaeda trademark and, in conjunction with the group’s long antipathy for Bhutto, further ties it to the attacks. Multiple suicide attackers were deployed against the US embassies in Africa in 1998; on Sept. 11; in the al-Qaeda-directed attacks in London in 2005; and in several other al-Qaeda operations. Bhutto’s more secular enemies, of whom there were many, would have been hard-pressed to recruit the four suicide attackers needed for the October and December operations. For al-Qaeda and its affiliates, by contrast, recruiting suicide attackers is very easy.

What’s more, assassination is the oldest tactic in the al-Qaeda playbook. The day after Bhutto’s death, Time magazine ran an ill-informed story suggesting that assassination was a new tactic for al-Qaeda. But, as far back as 1981, Egypt’s Jihad Group, which would morph into al-Qaeda, helped kill Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. Al-Qaeda’s first act of international terrorism came in 1991, when an assassin was dispatched from Pakistan to kill the king of Afghanistan, then living in Rome. (He survived.) A decade later, on Sept. 9, 2001, in a curtain-raiser for the Sept. 11 attacks, al-Qaeda targeted another popular Afghan leader, dispatching two suicide bombers to kill Ahmad Shah Massoud, the commander of the Northern Alliance then battling the Taliban. In short, al-Qaeda has a long history of mounting assassinations against Western-leaning leaders who stand in the way of its Taliban-style plans.

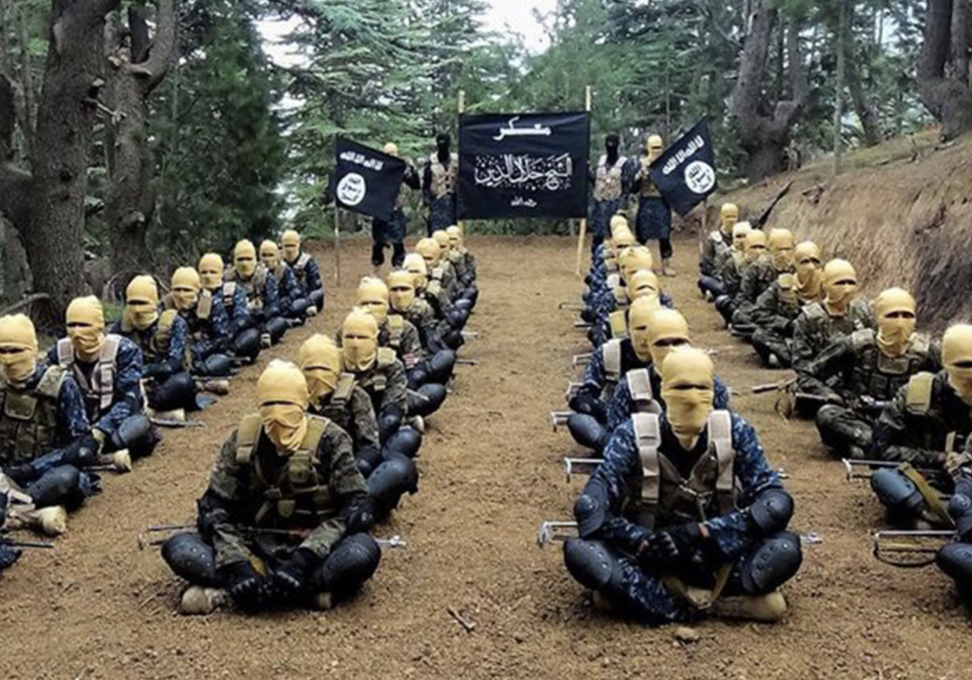

It is also relevant to the al-Qaeda thesis that, in the past several years, al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan have morphed together, ideologically and tactically. The Taliban conceives of itself as part of the wider global jihad spearheaded by al-Qaeda and deploys al-Qaeda-like suicide attacks, something it had previously eschewed. And both al-Qaeda and the Taliban increasingly see the Pakistani establishment as their enemy. Pakistani Taliban have attacked bases on the Afghan border and kidnapped Pakistani soldiers in the tribal areas in the past two years, while bin Laden and Zawahiri have, in recent months, called for attacks on the Pakistani Government. Two suicide attacks targeting Pakistan’s former interior minister in 2007 bore the marks of this al-Qaeda-Taliban alliance.

According to conversations I have had with several American counterterrorism officials, a number of groups that were once relatively distinct – a hundred-odd remnants of bin Laden’s team, a couple hundred “freelance” foreign fighters, several thousand members of the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban, and tens of thousands of Pakistani extremists – have, since Sept. 11, blended into one big family. A number of attacks in Pakistan since then, including the kidnapping and murder of Daniel Pearl, have counted diverse members of these groups as participants. (The US military says the February 2007 attack directed at US Vice-President Dick Cheney by a Taliban suicide bomber in Afghanistan was also organised by a high-ranking al-Qaeda commander.)

Which brings us back to the leader of the Pakistani Taliban, Baitullah Mahsud, a picture-book villain if there ever was one. In the few photographs that exist of him, he sports a “Pirates-of-the-Caribbean-meets-Mullah-Omar” look, his head wrapped in a shawl out of which his black curly tresses flow. According to a Western official, Mahsud is responsible for hundreds of deaths, many of them Pakistani soldiers and government officials killed in suicide operations.

Another Western official says the thirtysomething Mahsud is also hosting and protecting al-Qaeda members living with his tribe in southern Waziristan. In a recent interview, Mahsud gave the BBC my favourite line of the year: “Only jihad can bring peace to the world.”

Shortly after the Bhutto assassination, the Pakistani Government released a transcript of a phone call in which Mahsud yuks it up with a mullah crony, crowing: “Congratulations to you. Were they our men?” To which the mullah replies, “Yes, they were ours.” Through a spokesman, Mahsud later disavowed any role in the attack, but, ever since Pakistani authorities posted the audio of the call on a government website, Mahsud has said nothing to deny it’s his voice.

There is more to know about the network that planned Bhutto’s death. But the government has, so far, botched the investigation. After the December 2003 attempt on Musharraf’s life, the army corps commander tasked with the inquiry immediately sealed off the area and deployed the enormous resources of Pakistan’s three intelligence agencies, the police, and the army to track down the perpetrators. By contrast, shortly after the Bhutto hit, workers hosed down the park where she was killed, destroying the crime scene. “Hundreds of photos should have been taken,” commented Brad Garrett, an FBI special agent who spent four years working with the Pakistanis. “All blood stains and bomb residue should have been swabbed, and shell casings and bomb fragments should have been mapped to ‘freeze frame’ the scene.” None of this happened.

The investigation of Bhutto’s death has been marred not only by the characteristic incompetence of the Pakistani state, but also by the ham-handed manner in which Musharraf and his aides have seemed more eager to blame Bhutto for her own death than to mount a serious inquiry into what happened. Foria Younis, a former FBI special agent who spent years working terrorism cases in Pakistan after Sept. 11, told me, “There is the question of the will of the Pakistani police and government to want to solve these cases. It’s an uphill battle now. Witnesses will be afraid to speak up.”

Nonetheless, given the Mahsud audiotape and al-Qaeda’s history of targeting Bhutto and deploying assassins and suicide attackers, there is little doubt that Bhutto was killed in a joint Taliban-al-Qaeda operation. And experts predict more. In mid-December, Mahsud placed himself at the head of a coalition of militant groups in the tribal areas. “He is on a roll and feeling good about himself,” one official told me. “We can expect additional attacks.”

Despite hysterical analysis by the commentariat, however, Pakistan is not poised for an Islamist takeover similar to what happened in the Shah’s Iran. There is no religious figure around whom opposition to the Pakistani Government could form, and the coalition of Pakistani Islamist parties known as the MMA are polling at around four percent.

In the last three years, Pakistani support for suicide attacks has dropped from 41 percent to nine percent. Pakistanis are fed up with the militants. On Feb. 18, they will go to the polls and, if the election is even somewhat fair, will likely deliver a resounding defeat to the Islamists and a victory for the PPP and other secular opposition parties. As Benazir Bhutto was fond of saying, “Democracy is the best revenge.”

Peter Bergen, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation, is the author of Holy War, Inc. and The Osama bin Laden I Know. © The New Republic, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Afghanistan/ Pakistan