Australia/Israel Review

How Trump should deal with the Iran deal

Feb 1, 2017 | Emily B. Landau

Emily B. Landau

The debate over the fate of the Iran nuclear deal – or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – ahead of Donald Trump’s inauguration has for the most part been presented in black and white terms. Either the deal is terrible, and should be scrapped altogether, or it is working and should be preserved, even serving as a model for other proliferation challenges.

But there is a growing group of experts who are critical of the deal but are nevertheless not advocating that it be renounced by the new Administration. Not surprisingly, some supporters of the deal have been quick to mock critics who now say it is better to keep the deal, but this only underscores their inability to incorporate complexity and nuance when it comes to the JCPOA. Because at the heart of the third option is the need to make the best of a bad situation: to take into account what is feasible and realistic at this point, while working to fix what sorely needs fixing.

What is needed is to take stock of the JCPOA and of the post-deal dynamics: to take a hard look at what is in the text and what has developed surrounding the text; to assess Iran’s post-deal behaviour, and the attitude the Obama Administration has displayed toward Iran. On the basis of this review, the Trump Administration should formulate a new and comprehensive US approach.

Why Not Scrap the Deal?

What are the grounds for arguing that although the deal is weak and seriously flawed, it would nevertheless be unwise for the Trump Administration to scrap it? First, such a step would cause unnecessary friction with the other P5+1 partners, who have decided to accept the deal, ignore its problematic aspects, and move forward with economic – and, for some, military – deals with Iran. The EU advocates that the deal should continue to serve as a platform for building trust between the EU and Iran, even though Iran has displayed little if anything by way of trust-building in the 18 months since the deal was reached.

Second, a year and a half into the deal, Iran has already pocketed a significant amount of money – billions of dollars, some in hard cash – and has increased oil exports, so ditching the deal now would mean letting Iran off the hook with its nuclear obligations after Iran has gained much of the sanctions relief it was seeking (despite the complaints of the Supreme Leader).

The US would be left with little leverage to improve the situation. In fact, it would have to again try to build up the kind of pressure that Iran faced on the eve of the 2013 negotiation, which took a tremendous amount of time and energy. Moreover, while the US can cause significant pressure with its own financial sanctions, it would no doubt also have to work hard to bring other states on board for additional economic sanctions.

Finally, there is much that can be done to improve the circumstances surrounding the deal, without renouncing or renegotiating it.

Clarifying that Iran pursued a military capability

An important initial step that the Trump Administration should take is to state clearly and publicly that Iran violated the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) for decades, while working on a military nuclear program. All that is required in this regard is a change of rhetoric, because the conclusion that Iran advanced a military nuclear program has already been reached by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

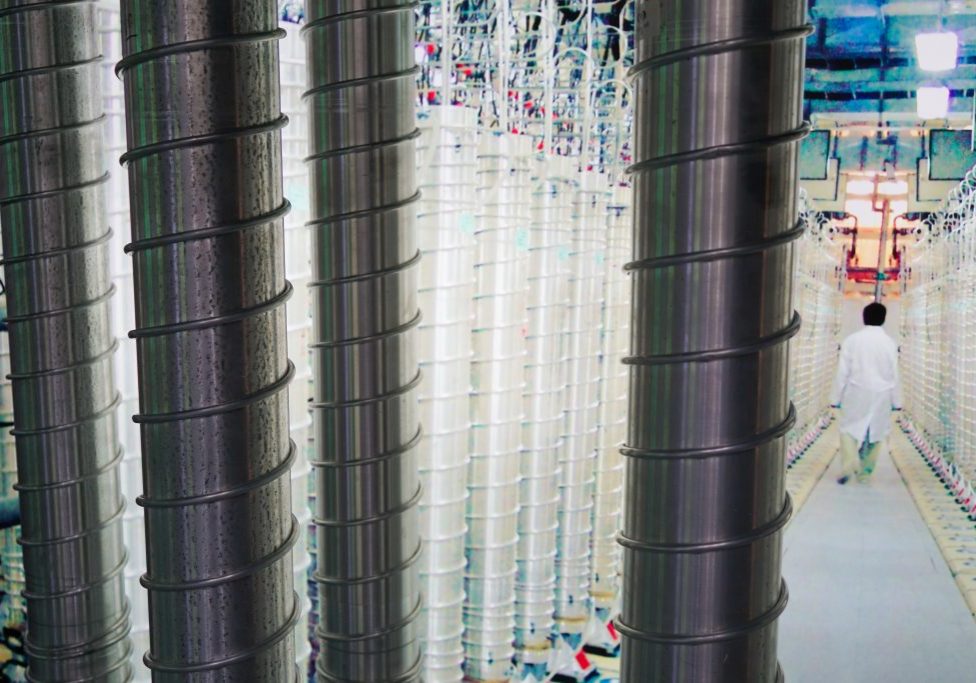

Indeed, the definitive IAEA report on the question of what is known as the Possible Military Dimensions (PMD) of Iran’s program was issued in December 2015. According to the report, Iran worked on a military program until 2003, and in a less coordinated manner until at least 2009. Significantly, the IAEA could not say anything more conclusive than this because even after the JCPOA was announced in mid-July 2015, Iran refused to cooperate with the IAEA’s investigation into the PMD. And even with partial cooperation, the conclusion is damning.

But once the report was released, it was immediately and inexplicably shelved; there was no further discussion of the matter, and Iran’s lack of cooperation with the IAEA investigation was ignored.

Implications for confidentiality, IAEA reports, and ballistic missiles

Publicly clarifying Iran’s problematic past is critical because Iran denies it ever worked on a military nuclear program, and has clung to its narrative of nuclear innocence, unchallenged by the P5+1. Declaring that Iran is a violator of the NPT is a necessary precondition for demanding clarifications regarding other issues stemming from the deal – three of which deserve special mention.

The first goes to the confidentiality that Iran seems to have been granted in some of its dealings with the IAEA, that we only learned about over the course of 2015 and 2016. The issue was first exposed regarding the inspection carried out at Parchin (a military site) in September 2015, and in mid-2016 it cropped up again following media reports on Iran’s enrichment plans for year 11 of the deal. These confidentiality privileges were explained by the P5+1 as normal procedure between the IAEA and NPT member states. But Iran is obviously not a normal member of the NPT and should not enjoy such privileges – it is a violator of the treaty, and has not cooperated with the IAEA in its investigations. There is no justification for granting confidentiality, which clearly works in Iran’s favour.

A second problem is that the IAEA reports on Iran’s nuclear program that have been issued since Implementation Day bear little resemblance to previous reports. The four reports released since January are missing essential technical details and data that had been included in all past reports and that enabled independent assessment of Iran’s compliance. Again, taking into account that Iran has a proven record of NPT violations, there is no justification for omitting this crucial information.

Finally, clarifying Iran’s past work on a military nuclear program feeds into the missile realm as well. This issue is a little trickier than the previous two, because whenever the issue of ballistic missiles is raised, the standard response is that these were not part of the nuclear negotiations. But this response is not satisfactory, because the P5+1 agreed not to include ballistic missiles as a concession to Iran, not because they are not closely tied to a military nuclear program.

In fact, to be a nuclear-capable state in today’s world implies ballistic missile capabilities for delivering nuclear warheads. So the connection is intimate. Moreover, Iran demanded a change in the wording of UN Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2231 which endorsed the JCPOA and replaced all the previous UNSC resolutions on Iran, including Resolution 1929 from June 2010 that had strong wording regarding ballistic missiles. In the new resolution, Iran was only called upon (not required) to stop work on ballistic missiles; moreover, Resolution 2231 refers to ballistic missiles that were designed to be able to carry a nuclear payload. The added words (“designed to”) are important, and they go directly to Iran’s insistence on maintaining its narrative of nuclear innocence. Because if Iran never worked on a military capability (as it falsely claims), and has no intention of doing so in the future, then obviously it cannot be accused by the international community of working on a ballistic missile designed to carry a nuclear warhead. For this reason as well, it is important to refute Iran’s nuclear fairy-tale, and replace it with the truth.

When one appreciates the benefits that accrue to Iran from its narrative of “nuclear innocence” – its ability to be treated as a “normal” member of the NPT vis-a-vis the IAEA reports that don’t divulge full details of its nuclear program, confidentiality privileges on the issue of the inspection of Parchin, and Iran’s nuclear plans from year 11, as well as on the missile front – it is clear why Iran refuses to give it up.

Less comprehensible is the P5+1 acquiescence to this falsehood. The standard explanation provided by the US for not pressing Iran on the PMD was that they preferred to focus on Iran’s future behaviour, which should be monitored regardless of what it did in the past. Moreover, pressing Iran would not serve any purpose because “we know what Iran has done”; it would only cause humiliation. But refusing to clarify Iran’s record of violations was a mistake, with negative ramifications. Bringing these violations to the forefront is not about humiliating Iran, but about denying it any benefits from this false narrative.

Keeping Iran to its commitments and responding to violations

It would seem to be self-evident that Iran must be kept to its JCPOA commitments, but ensuring this is not as simple as it might seem, and many relevant questions have no answer in the text. What constitutes a significant violation? What line does Iran have to cross to elicit a response? If there is a need to respond, who will do so, and by what means? Formulating clear responses to these questions, and policy on that basis, was something that should have been done in the very first stage – once the JCPOA was announced – but there is no evidence that it was.

The Obama Administration seems satisfied with the laconic formulation of having ample time to detect a violation and deal with it, if necessary by means of “snapback” sanctions. But obviously this does not provide clear direction, or the answers to the chain of decisions that will in reality have to be made. While “snapback sanctions” might sound good on paper, it is not likely to work in practice, because sanctions do not simply “snap back” – states need to decide whether to reinstate sanctions, and which sanctions to reinstate. This will no doubt elicit heated discussions, and the process will take time.

Complicating matters over the past year was that the Obama Administration actually had no interest in these clarifications; to the contrary, due to its strong commitment to the deal, it was not motivated to seek out violations, to make note of them when revealed, or to think about proper responses. Indeed, violations – such as appear in the fourth IAEA report issued in early November 2016 – have been played down, and other suspected transgressions – specifically regarding lack of Iranian adherence to the JCPOA Procurement Channel – have been brushed aside. With political distance from the deal, and having seen first-hand Obama’s lack of response, the Trump Administration will be better positioned to tackle this issue.

Change the US attitude toward Iran

The Obama Administration negotiated a very problematic nuclear deal, and then proceeded to weaken the US in its dealings with Iran over the past year-and-a-half. In order to sell the deal, the Administration misled the American public by presenting the choice as between this deal or war, and hinted that a deal with Iran could very well engender better US-Iran relations, although there was no sign that this was a realistic expectation.

In an effort to continue to maintain the JCPOA over the past year, and despite growing evidence of Iranian misbehaviour and lack of interest in improving relations, the Obama Administration played up Iran’s (minimal) cooperation while ignoring or explaining away its regional aggression and deal violations. The Administration allowed itself to be deterred by Iranian complaints and accusations of US noncompliance with the JCPOA; indeed, rather than clarifying that the complaints have no leg to stand on, US Secretary of State John Kerry responded by trying to convince companies to go back to business with Iran. The more the Administration acquiesced to Iran, the stronger Iran has become. This translated into significant leverage for Iran and a corresponding loss of leverage for the US.

A major change in the US approach to Iran and the nuclear deal is sorely needed. The US must stop playing the role of Iran’s lawyer and defender, and begin holding it to the terms of the deal, while responding firmly to Iran’s attempts to push the envelope not only with regard to the deal, but in its aggressive regional behaviour as well. The US should state clearly that it will continue to resist what Iran is doing in the missile realm, and its support for terror – and the recent Senate vote (99-0) to renew the Iran Sanctions Act is a step in the right direction.

The Obama Administration tried to separate the nuclear issue from other aspects of Iran’s behaviour, arguing that it only wanted to roll back Iran’s nuclear activities. But when it dangled the prospect of a more moderate Iran as reason to support the deal, it was implicitly underscoring that there actually is an important connection between the nuclear issue and Iran’s overall profile. The same logic should be applied when thinking about the sunset provision in the deal. If there is no change in Iran’s basic motivation and behaviour – and no indication of a strategic U-turn in the nuclear realm – the JCPOA restrictions should not be lifted according to an arbitrary timetable. Rather, substantive benchmarks for lifting restrictions should be formulated.

All of these steps can go a long way to improving the situation vis-à-vis the JCPOA, without renouncing or renegotiating the deal, perhaps with the exception of introducing benchmarks for implementing the sunset provisions. Moreover, there is no apparent reason why the other P5+1 members would oppose this new approach, as it is geared in the main to exposing and correcting some bad practices that have been put in place in dealing with Iran’s demands and complaints, while clearing up debilitating ambiguities and puzzles regarding the deal.

The Trump Administration would be well advised to decide on procedures for dealing with the kind of defiant behaviour that Iran is likely to display.

Changing course on Iran will not be easy, and will likely be met with resistance, first and foremost from diehard supporters of the deal. But a new administration – not committed to and bound by the poor decisions that have already been taken – is best positioned to take a fresh and critical look at the deal, and introduce much needed improvements.

Dr. Emily B. Landau is a senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) at Tel Aviv University, and head of the Arms Control and Regional Security Program. © Fathom Magazine (fathomjournal.org), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: International Security