Australia/Israel Review

How to tell whether an Iran Deal is acceptable

Jul 8, 2015 | Michael Singh

Michael Singh

If Iran and the P5+1 powers reach a nuclear accord this summer, members of Congress, presidential candidates and the public will need to assess whether the deal is acceptable. This will require evaluating the strength or weakness of each individual provision on its own merits. Perhaps more important, this evaluation will need to consider the big picture: What objectives do Iran and the P5+1 (US, UK, Russia, China, France and Germany) accomplish via the agreement?

IRAN’S OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGY

Iran’s primary objective in the nuclear talks, as inferred from its actions and negotiating positions, is twofold: to free itself from sanctions, diplomatic isolation and military threat, while maintaining the capabilities necessary to develop a nuclear weapon in the future should it choose to do so. These are not Iran’s only objectives, to be sure; they fit within a larger strategy that aims to secure the regime, project Iranian power, and enhance Iranian prestige. Nor are Iran’s views monolithic; for example, significant disagreement exists among Iranian officials regarding the extent to which the country should open its economy to foreign trade and investment. Yet relief from pressure and preservation of a nuclear weapons option appear to be guiding Iran at the negotiating table.

Complicating matters for Teheran, these two aims stand in opposition to each other – obtaining sanctions relief calls for limiting its nuclear activities, while truly arriving on the threshold of a nuclear weapon requires advancing them. Iran’s strategy has thus been to protect those elements of its nuclear program essential to any future effort to produce a weapon. Such an effort would require producing weapons-grade nuclear fuel, “weaponizing” that fuel in the form of an explosive device, and mounting that weapon on a delivery vehicle, likely a ballistic missile. These activities would most likely have to be clandestine, as producing nuclear weapons is proscribed by the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

THE LAUSANNE FRAMEWORK

So far, the negotiations have not foreclosed the possibility of Iran accomplishing both of its objectives. While the deal parameters announced in Lausanne on April 2 left important questions unresolved, they raise the prospect of significant sanctions relief without clearly denying Iran what is required to maintain a nuclear weapons capability and undertake a future clandestine effort to develop an actual weapon.

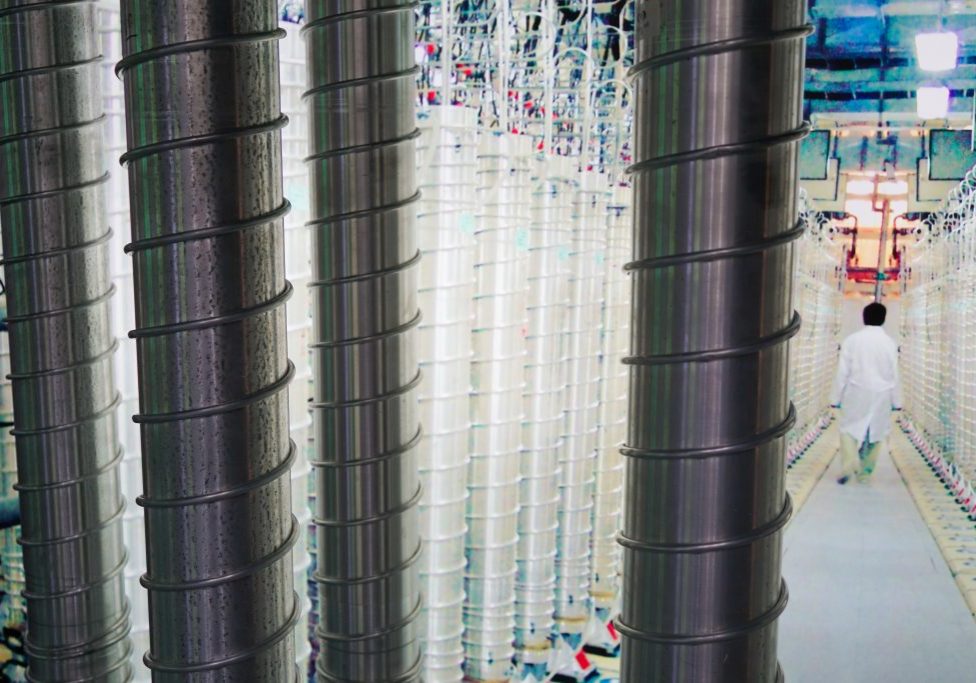

Nuclear fuel. The deal currently under negotiation may leave Iran with three elements essential to clandestinely producing the highly-enriched uranium (HEU) required to fuel a nuclear weapon. First, it leaves Iran with a large, legitimised nuclear fuel fabrication supply chain – mining, milling, converting, and enriching uranium; the manufacture of centrifuges and related technology; and the storage of fuel and centrifuges in various stages of usability. The deal’s current parameters would also permit Iran to continue conducting R&D on advanced centrifuges. This work could dramatically reduce the number of centrifuges required to produce HEU, enabling Iran to do the work in a smaller and thus more easily concealed facility.

Weaponisation. While the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and Western intelligence agencies have already gathered a significant amount of information on Iran’s past and possibly ongoing weaponisation efforts (termed “possible military dimensions” or PMD), Teheran has resisted answering the IAEA’s questions about these efforts or providing access to key personnel and facilities reportedly involved in them. Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has publicly insisted that inspectors will not be permitted to speak to Iranian nuclear scientists, and Iranian officials have asserted that the IAEA’s PMD inquiries lack any legitimate basis. For Iran, shielding weaponisation efforts from the IAEA preserves its ability to use the involved personnel, facilities and research in any future bomb-making effort.

Delivery vehicle. Iran already reportedly possesses the largest, most sophisticated ballistic missile arsenal of any non-nuclear weapons state, and US officials believe it is working on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). While this missile work has been the subject of UN Security Council and US sanctions, Khamenei has declared it off limits for the nuclear talks; the issue was referred to only obliquely in the November 2013 “Joint Plan of Action” interim accord and appears to have been dropped by P5+1 negotiators since then.

P5+1 OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGY

If Iran is trying to preserve its nuclear weapons option, one might expect that the objective of the United States and its partners would be to prevent it from doing so. In fact, however, American objectives in the negotiations have shifted. At the inception of the P5+1 talks, the US goal was indeed to prevent Iran from possessing a nuclear weapons capability.

With the Joint Plan of Action, however, the aim of dismantlement was renounced by the P5+1. Instead of denying Iran a nuclear weapons capability, the US goal now appears to be preventing Iran from building an actual weapon while implicitly ceding the capability. Toward this end, negotiators hope to restrict Iran to a one-year breakout timeline (i.e., the time required to produce one weapon’s worth of HEU) at its declared facilities for the next decade through Teheran’s voluntary acceptance of limits on its nuclear activities, while relying on stepped-up inspections to ensure that it does not pursue an undeclared parallel program aimed at producing a weapon.

Broadly speaking, US officials offer two reasons for this shift in objective. First, they assert that the increased presence of inspectors will ensure Iran is unable to pursue a clandestine weapons effort, whereas failing to reach an agreement would mean reduced inspections. Second, they insist that Iran will not agree to more far-reaching restrictions, and that the alternatives to the deal being negotiated would be worse.

Both arguments are problematic, however. The value of increased inspections would be mitigated by several factors, including restrictions placed on inspectors (e.g., lack of timely access to military sites and Iran’s continued refusal to address PMD inquiries), limitations on the scope of inspections (e.g., the exclusion of Iran’s missile program), and the expanded range of nuclear activities in which Iran is permitted to engage. The downplaying of US alternatives underestimates the deterrent value of economic and military pressure. However unappealing America’s alternatives may be, Iran’s alternatives are worse, given the state of its economy and its vulnerability to military threats.

THE WAY FORWARD

The Obama Administration is unlikely to return to the previous goals of requiring Iran to dismantle its nuclear infrastructure or cease, even temporarily, its uranium enrichment. Nor is it likely to insist that Teheran alter non-nuclear policies such as support for terrorism and destabilising regional activities as a condition for sanctions relief. These facts alone ensure that any nuclear deal will fall well short of longstanding US goals and face significant opposition in Washington and among allies in the Middle East.

Yet if the Obama Administration wishes to maximise support for a deal and avoid the possibility that it is rejected by Congress or – far worse – that it sets back US interests rather than advancing them, it can and should hew as closely as possible to its previous objective of denying Iran a nuclear weapons capability, rather than merely seeking to prevent Teheran from exercising that capability. Leaving Teheran unfettered by sanctions or military threat, yet with the option to clandestinely produce a nuclear weapon – and, upon the expiration of the accord’s restrictions, leaving it as a nuclear weapons threshold state – reduces the cost to Iran of trying to develop a nuclear weapon when conditions permit, while increasing the possibility that other regional states will seek nuclear weapons capabilities of their own.

Denying Iran a nuclear weapons capability – or at least severely constraining it – remains possible even at this late stage of the talks. Doing so would require defending the Lausanne framework’s most useful provisions (e.g., relating to long-term inspections of Iran’s nuclear supply chain) and significantly strengthening other elements. These should include:

- denying Iran licence to conduct centrifuge R&D;

- insisting on the inspection of any sites deemed suspect by the IAEA, including military sites;

- insisting that Iran answer the IAEA’s PMD inquiries and provide related access as a precondition for any sanctions relief; and,

- placing limits on Iran’s missile work, especially that which is applicable to the design and development of nuclear-capable re-entry vehicles and ICBMs.

In addition, the agreement’s duration should be based not solely on time, but also on the judgment of the IAEA and UN Security Council that Iran has restored international confidence in the peaceful intent of its nuclear activities. Similarly, any sanctions or financial relief should be phased according to Iranian performance, and sanctions related to matters not addressed by the agreement (e.g., terrorism sponsorship) should remain in place altogether and be zealously enforced. Furthermore, the deal should be buttressed by a broader allied strategy designed to enforce its provisions, deter and respond meaningfully to violations, strengthen regional alliances, and uphold global non-proliferation norms.

This is a long but not especially onerous list of requirements, which are for the most part compatible with the parameters announced in Lausanne. They would, however, force Iran to choose between its twin objectives of relieving sanctions pressure and maintaining a nuclear weapons option. Teheran can thus be expected to resist, meaning that the negotiations would require additional time or even suffer temporary breakdowns. Yet this is an acceptable risk to achieve an accord that durably places nuclear weapons beyond Iran’s reach.

Michael Singh is the Lane-Swig Senior Fellow and managing director at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. © Washington Institute, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

* This article is featured in this month’s Australia/Israel Review, which can be downloaded as a free App: see here for more details.

Tags: International Security