Australia/Israel Review

Force-ful Action

Aug 1, 2006 | External author

Problems and Prospects for International Troops in Lebanon

By Michael Eisenstadt

As diplomacy to halt the violence in Lebanon slowly gathers momentum, US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has endorsed the idea of an international “stabilisation force” to keep the peace, seconding proposals previously put forward by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Such a force, however, is liable to face major obstacles and incur substantial risks that could jeopardise its prospects for success. For this reason, it is essential to consider what past experiences in Lebanon, the Middle East, and elsewhere teach about peacekeeping and peace enforcement operations.

|

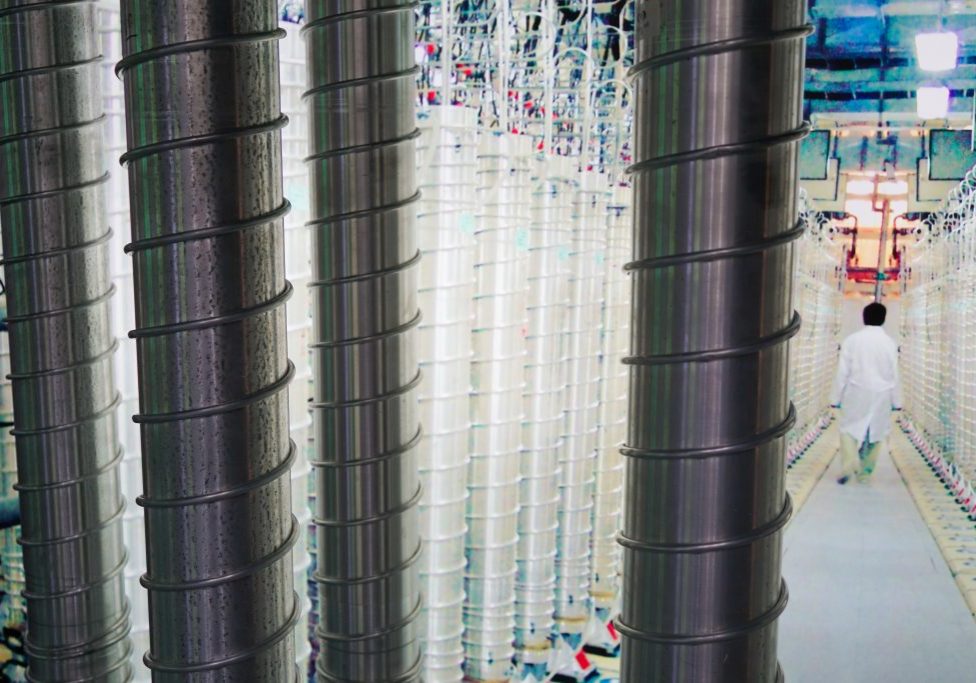

| Keeping the Peace?: UNIFIL provides useful lessons in what not to do |

The UNIFIL Experience

The experience of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) – the current UN peacekeeping operation in southern Lebanon – provides a number of important lessons for those hoping to create a new force to take its place. UNIFIL was established in March 1978, in the wake of a bloody seaborne attack by Lebanon-based PLO terrorists, and the subsequent Israeli invasion of southern Lebanon. The UN created UNIFIL to confirm the withdrawal of Israeli forces, restore international peace and security, and ensure the return of central government authority to southern Lebanon, in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 425.

UNIFIL is widely considered a failure; in particular, it failed to prevent attacks on Israel that sparked the 1982 invasion of Lebanon, major flare-ups with Hezbollah in 1993 and 1996, and the current round of fighting. There are several reasons for these failures: (1) UNIFIL was hastily organised as an “interim” force to prevent events in Lebanon from derailing US efforts to advance and broaden the then still-fragile Egyptian-Israeli peace process; (2) UNIFIL operated in accordance with traditional peacekeeping principles: impartiality in its dealings with local entities (even terrorist groups) and restraint in the use of force to keep the peace; (3) UNIFIL, even at its peak strength of 6,000 soldiers and observers (today its strength stands at 2,000), lacked the manpower necessary to secure its entire area of operations.

Several lessons can be drawn from the UNIFIL experience. Getting the terms of reference and the makeup of a stabilisation force right at the outset are essential, as there may not be a second chance to correct flaws that could prove fatal to the mission. And a new international stabilisation force will need to be much larger and more robust than UNIFIL – consisting of perhaps 15,000-20,000 soldiers and observers, and it should operate under much more permissive rules of engagement.

Peacekeeping/Peace Enforcement Lessons Learned

Important lessons can be learned from other peacekeeping and peace enforcement operations in the Middle East and elsewhere. Since the creation of Israel in 1948, there have been seven Arab-Israeli peacekeeping operations: five were sponsored by the UN, and two involved “coalitions of the willing.” Those operations that failed or that failed to make a difference – the UN Truce Supervision Organisation (UNTSO), the UN Emergency Force (UNEF I), UNIFIL, and the Temporary International Presence in Hebron (TIPH) – did so because the underlying sources of conflict had not been resolved prior to their deployment, and because they lacked the mandate or ability to enforce the peace. Those that succeeded – the UN Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) in the Golan, and the Multi-National Force and Observers (MFO) in the Sinai – did so because the involved parties were interested in keeping the peace along their respective borders.

The UN has conducted a large number of peacekeeping/peace enforcement operations elsewhere, including Somalia, Bosnia, and Kosovo, while NATO has led peacekeeping operations in Bosnia and Kosovo.

Though reflecting a variety of circumstances, a number of lessons can be drawn from these experiences that should be borne in mind by those considering a stabilisation force for Lebanon: (1) International forces have been most successful when they monitored political arrangements already reached, and not when they attempted to impose a settlement by force of arms; (2) In cases where political arrangements have not been reached, international forces often face the choice of being drawn into ongoing conflicts and risking international support for the mission, or staying above the fray and risking irrelevance; (3) Dealing with local spoilers who are often quite resourceful at disrupting peace-building efforts requires both substantial reserves of political will and the commitment of significant military resources; (4) In peace enforcement operations, international forces often become an integral part of the new political order, and key to preventing renewed outbreaks of violence. For this reason, peace enforcement operations often turn into open-ended commitments that may last for decades.

Setting Conditions for Success

Whether a stabilisation force for Lebanon succeeds or fails will depend heavily on several factors: its political and operational environment, its mandate, and how it is equipped, organised, and led.

Political and Operational Environment. For the stabilisation force to succeed, the right political and military circumstances must be created in Lebanon prior to its arrival. Hezbollah must be severely weakened – militarily and politically – and the Lebanese government (which includes Hezbollah) must consent to the presence of such a force, lest it be seen as an occupying force to be resisted and fought.

Hezbollah will likely emerge from the current conflict with greatly diminished capabilities – particularly its ability to fire rockets into Israel. It is, however, likely to retain the capacity to wage guerrilla warfare and undertake acts of terrorism. As a result, Hezbollah will retain a significant ability to harass or attack a stabilisation force, should it choose to do so.

Mandate. A stabilisation force must have a clear, achievable mandate, perhaps in the form of a UN Security Council Resolution backed by an Arab League endorsement. Countries sending contingents must understand that by participating in such a force, they are signalling their willingness to potentially commit their contingent to combat with Hezbollah, and that retribution could take the form of terrorist attacks – bearing in mind the experiences of the Multi-National Forces (MNF) in Beirut from 1982-1984, which were attacked by Hezbollah, with the support of Syria and Iran. Failure to recognise this possibility up front could jeopardise the mission down the road should the going get tough.

The principle mission of a stabilisation force should be to assist the Lebanese government to comply with Security Council Resolution 1559 by verifying the withdrawal of Iranian advisors from Lebanon, disarming Hezbollah (and other armed groups in their area of operations, including Palestinian extremists and al-Qaeda elements), and supporting the extension of Lebanese Government control to the Israel-Lebanon border. Its rules of engagement should allow all national contingents to use lethal force in fulfilment of its mandate as well as for self-defence; national reservations to the rules of engagement should be proscribed at the outset.

That said, the stabilisation force should fulfil its mandate, whenever possible, by working with and through Lebanon’s Internal Security Forces (ISF) and the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF). An implied task for the stabilisation force, then, would include training the ISF and LAF so that they can eventually assume responsibility for ensuring peace and stability in Lebanon.

Force Structure and Capabilities. A stabilisation force should be strong enough to deter open challenges to the LAF and to its own authority. A force of perhaps 15,000-20,000 could be required, consisting of armor, light and mechanised infantry, light artillery, and special operations forces, capable of undertaking civic action, foreign internal defence assistance, and combat (particularly counterinsurgency and counterterrorist) operations. Countries that might participate in such a mission reportedly include France, Turkey, Italy, Brazil, Pakistan, India, and Germany.

Moreover, the force must be able to help the Lebanese Government deal with reconstruction challenges and to replace Hezbollah and UNIFIL as the primary provider of social services to the population of southern Lebanon. It should include civil engineers to help rebuild roads and repair the power grid, and civil affairs specialists to provide assistance in the fields of public health, education, local administration, and so forth. And its mandate should allow it to use force against those who attempt to interfere with the extension of central government authority in its area of operation.

The main body of the stabilisation force would probably deploy to the general area now occupied by UNIFIL between the Israel-Lebanon border and the Litani River, to prevent cross-border attacks and the launch of short-range rockets. Mobile patrols might operate elsewhere in south-central Lebanon and in the southern suburbs of Beirut, in support of LAF efforts to disarm Hezbollah and other armed groups, to locate arms and rocket caches, and to investigate security incidents related to the fulfillment of its mandate.

Finally, there should be a liaison element to co-ordinate with monitors at Lebanon’s border crossings and ports of entry, to prevent Hezbollah’s rearmament from abroad in accordance with Security Council Resolution 1680 and to coordinate with the Israel and Lebanese militaries.

The mandate, terms of reference, rules of engagement, composition, and leadership of an international stabilisation force for Lebanon should be carefully weighed, for past peacekeeping and peace enforcement experiences and the Lebanese operational environment provide more than ample reason to believe that this will be a high-risk mission that will pose major challenges for the force. Much will also depend on how the current crisis ends, and on the strategy that Hezbollah adopts in its aftermath. For this reason, it is vital that the international community bring maximum pressure to bear on Hezbollah to disarm, and warn both Hezbollah and its Iranian patrons that attacks on a stabilisation force could have grave consequences for both, so that the force does not become a terrorist target or another asset that Teheran can implicitly threaten in order to deflect international pressure from its nuclear program.

![]()

Michael Eisenstadt is a Senior Fellow and Director of Security Studies at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. © Washington Institute, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: International Security