Australia/Israel Review

Essay: The Iranian Nuclear Challenge

Sep 26, 2008 | Bipartisan Policy Center

What follows below is excerpted from the executive summary of an important new report entitled “Meeting the Challenge: US Policy toward Iranian Nuclear Development”, published by the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington on September 19. It is the work of an independent bipartisan panel assembled by the centre, chaired by former US Senators Daniel Coats (R-Indiana) and Charles Robb (D-Virginia), and including senior policy advisers from the Obama, McCain and Clinton campaigns. It is intended to inform the policy-making of the next US president with respect to the crucial foreign policy conundrum of the Iranian nuclear program. Iran expert Dr. Michael Rubin, who recently visited Australia as a guest of AIJAC, served as a key consultant to the committee which authored the report. The full report, with complete analysis and documentation, can be downloaded from the website of the Bipartisan Policy Center, www.bipartisanpolicy.org.

I. Introduction

A nuclear weapons-capable Islamic Republic of Iran is strategically untenable. This report is about preventing the untenable.

While a peaceful, civilian nuclear program in Iran might be acceptable under certain conditions – including an external source of nuclear fuel and a stringent safeguards and inspections regime – it is the decided judgment of this group that continued Iranian enrichment of uranium and ineffectively monitored operation of the light water reactor at Bushehr threatens US and global security, regional stability, and the international nonproliferation regime. As a new president prepares to occupy the Oval Office, the Islamic Republic’s defiance of its Non-Proliferation Treaty safeguards obligations and United Nations Security Council resolutions will be among the greatest foreign policy and national security challenges confronting the nation.

We believe a realistic, robust, and comprehensive approach – incorporating new diplomatic, economic and military tools in an integrated fashion – can prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons capability. This comprehensive approach should feature a new diplomatic strategy underpinned by carefully calibrated financial and military leverage… There are no magic formulas or silver bullets that will resolve this grave challenge easily, and all courses of action or inaction carry serious tradeoffs. Instead, the Iranian threat requires a serious bipartisan strategy that is coordinated with our allies, addresses concrete realities and advances US national security.

II. Findings

Threat

Iran’s nuclear development may pose the most significant strategic threat to the United States during the next administration. A nuclear-ready or nuclear-armed Islamic Republic ruled by the clerical regime could threaten the Persian Gulf region and its vast energy resources, spark nuclear proliferation throughout the Middle East, inject additional volatility into global energy markets, embolden extremists in the region and destabilise states such as Saudi Arabia and others in the region, provide nuclear technology to other radical regimes and terrorists (although Iran might hesitate to share traceable nuclear technology), and seek to make good on its threats to eradicate Israel. The threat posed by the Islamic Republic is not only direct Iranian action but also aggression committed by proxy. Iran remains the world’s most active state sponsor of terrorism, proving its reach from Buenos Aires to Baghdad.

Even if Teheran does not actually build or test a nuclear weapon, its establishment of an indigenous enrichment capability places the region under a cloud of ambiguity given uncertain Iranian capacities and intentions. Such ambiguity will give the Islamic Republic a de facto nuclear deterrent, which could embolden it to reinvigorate its export of revolution and escalate support for terrorist groups…

We do not believe that analogies to Cold War deterrence are persuasive, and its proponents appear to us to have underestimated the difficulties of applying it to Iran. First, nuclear deterrence was less effective than commonly assumed; the United States and Soviet Union nearly stumbled into nuclear conflict on several occasions. Secondly, the Islamic Republic’s extremist ideology cannot be discounted. While most Iranians care little for the theological exegesis of their rulers, the nuclear program remains within the grasp not of the president, a transient figure in Iran’s power structure, but rather with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and the Office of the Supreme Leader, proponents of extreme ideologies.

Achieving nuclear capability would make the Islamic Republic not only a regional threat, but also an international one. A nuclear Islamic Republic would, in effect, end the Non-Proliferation Treaty security regime. Many, if not most, regional states might feel compelled to develop their own indigenous nuclear capability or accept coverage from another state’s nuclear umbrella. Given historical instability in the region, the prospects of a nuclear Middle East – possibly including Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Turkey – are worrying enough, even before the proliferation cascade continues across North Africa and into southern Europe…

State of Play

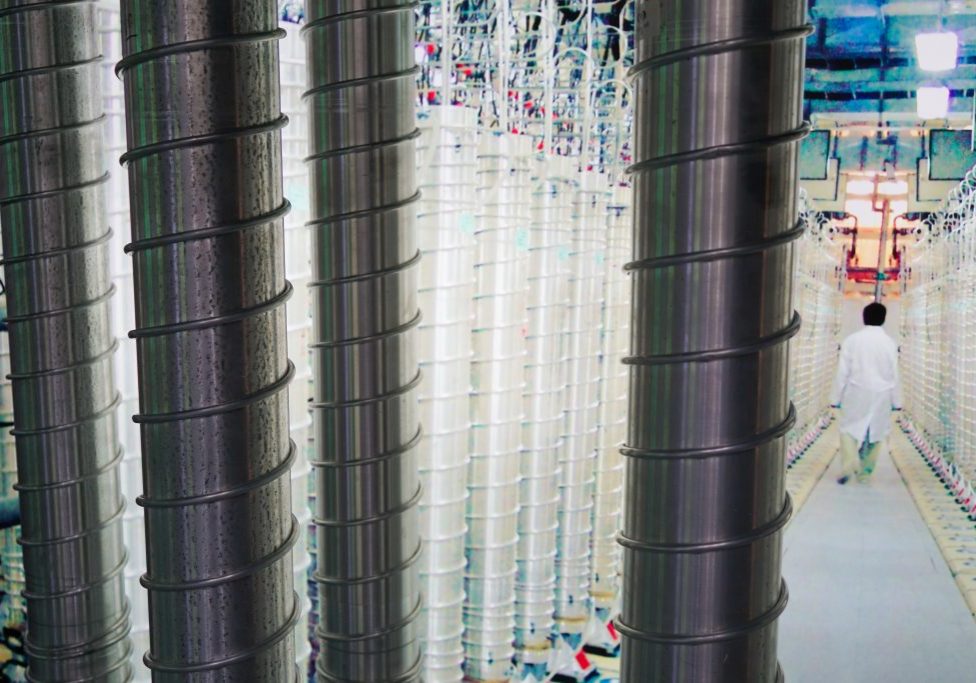

While we agree that diplomacy should underlie US strategy, we also acknowledge that the current US and European diplomatic approach and several United Nations Security Council resolutions have not succeeded in stopping Iran from developing its nuclear capacity. Since exposure of its clandestine enrichment program in 2002, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has found that the Iranian Government has installed 4,000 centrifuges in a facility designed to hold 50,000. We recognise that IAEA inspections are insufficient. By the IAEA’s own mandate, the organisation can only inspect declared nuclear facilities. Even if Iranian authorities are discovered to have constructed parallel but clandestine enrichment facilities, IAEA inspectors would not necessarily be authorised to monitor them without Iranian consent. In addition, much of the Iranian enrichment debate overlooks the possibility that Iranian officials could produce plutonium in their heavy water plant at Arak or divert nuclear material from spent reactor fuel, whether from Bushehr, Arak or other nuclear plants.

While the 2007 National Intelligence Estimate reported that Iran suspended warhead design work in 2003, the National Intelligence Estimate does not leave room for comfort. Its artificial separation between military and civilian technology contradicts a reality where such distinctions cannot be made. Despite Teheran’s protestations, we do not believe its program is inherently peaceful in nature. Teheran has a long record of cheating and deception, and its extensive, if neglected, pipeline infrastructure suggests that Iranian officials would have far greater energy security had they invested a fraction of their nuclear program’s cost in further development of their natural gas fields and facilities, refinery construction and distribution network. Accordingly, we reject the Islamic Republic’s claim that its nuclear program is motivated only by energy concerns. We also agree that the Iranian Government’s legal argument that the Non-Proliferation Treaty allows its current nuclear development is not credible…

Commonly Discussed Solutions Won’t Work

The strategy we lay out focuses as much on what the United States must do to prepare for negotiations with the Islamic Republic as on the nature and objectives of these negotiations… Any US strategy should uphold the “DIME” paradigm and incorporate simultaneous diplomatic, informational, military, and economic strategies.

There are no risk-free solutions. The current diplomatic approach has not succeeded. Iran has crossed various redlines that the United States and the international community have set down, thereby eroding Iranian credibility as well as ours. There is ample evidence that Iranian leaders have accelerated their defiance of international norms even as the European Union, United States, and other powers have improved their incentive packages… Indeed, we specifically note the admission of [former President] Khatami’s former spokesman, Abdollah Ramezanzadeh, on June 15, 2008, that a strategy of insincere dialogue provided cover for the Islamic Republic to import technology used to further the Islamic Republic’s covert nuclear program. We also note Teheran’s rejection of guarantees of nuclear fuel and enrichment outside the Islamic Republic, both of which would meet the needs of any program motivated solely by energy concerns…

We believe it would be a mistake to acquiesce to Iran’s demand that it be permitted to enrich uranium under international inspections in Iran. Given the Islamic Republic’s history of nuclear deception and its ambition to obtain nuclear weapons and the limits of IAEA safeguards and procedures, we see no combination of international inspections or co-ownership of enrichment-related facilities inside Iran that could provide meaningful assurance to the international community that such facilities will not contribute to the nuclear weapons capability that Iran seeks…

There are three components to a nuclear weapon – the actual explosive device, delivery method, and fissile material – the latter of which is the most technically difficult to develop and most crucial to nuclear weapons capability. Therefore, we take “nuclear weapons-capable” to mean possession of 20 kilograms of highly enriched uranium or roughly six kilograms of plutonium, both conservative estimates of how much fissile material is necessary for a crude nuclear device. According to a study commissioned by this Task Force, under certain conditions, it would be technically possible for the Islamic Republic to enrich 20 kilograms of highly enriched uranium in four weeks or less; this could easily occur between IAEA inspections and make it difficult for the IAEA to detect. If nothing else, Teheran’s progress means that the next administration might have little time and fewer options to deal with this threat.

However, it is not too late for sanctions and economic coercion to work. Despite near record oil prices, Iran’s economy remains weak. While the United States, its European partners, and the United Nations have imposed some sanctions upon Teheran, each has a range of more biting financial tools at their disposal…

III. Recommendations

We believe that a new and comprehensive diplomatic strategy, with calibrated financial and military leverage, will be the next administration’s best option. We seek a diplomatic solution to the Iranian challenge, involving Washington’s direct engagement with Teheran, but only under the right conditions. We also recognise that a new president might need to turn to less optimal solutions if diplomacy fails within a reasonable timeframe…

Close coordination and allied support is critical to build the strength and leverage necessary for a viable diplomatic solution. Thus, before we can begin talking directly to the Iranian leadership, there are a number of steps that we must take to build leverage to use against Iran and coordinate more closely with our allies and other international players.

Alliance Building

First, the new president should clarify to the Europeans that only by standing firmly together diplomatically and ratcheting up the pressure on the Islamic Republic can we improve the chance to avoid more robust action. The Europeans make war more likely if they do not strengthen sanctions against Iran and effectively end all commercial relations.

Secondly, the White House will need to make every effort to convince regional allies like Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf emirates to pressure China and, eventually, Russia to join the United States in ratcheting up the diplomatic pressure on Teheran, both to achieve United Nations Security Council consensus and to assuage European concerns that Moscow and Beijing seek to capitalise on European commercial disengagement. (Of course, the conflict in Georgia has made Russian cooperation more challenging.) Given increasing demand for Middle Eastern oil and gas, especially in East and South Asia, states such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar have unique leverage over China and India…

Third, so long as Teheran feels confident that it enjoys Moscow’s support and protection, the likelihood of a diplomatic solution to the Iranian crisis diminishes. The United States must prioritise its effort to motivate Russia to step up its support for international efforts to pressure Iran to abandon its quest for nuclear weapons. One point of friction between the United States and Russia is the US initiative to install missile defences in Eastern Europe. The United States insists that these defences are directed against the emerging nuclear and missile threat from Iran. Moscow, however, has strongly objected to US missile defences in the Czech Republic and Poland on grounds that they pose a threat to Russia. The United States should make clear to Moscow that operationalisation of the initial missile defence capability, as well as any future expansion of it, will depend on the evolution of the nuclear and missile threat from Iran. Should Russia contribute to successful international efforts to restrain the Iranian threat, it will lessen the need to further develop and expand missile defences in Europe. Another potential source of US leverage over Russia relates to bilateral nuclear cooperation. Such cooperation is potentially valuable to Russia, not only with respect to commerce with the United States in nuclear goods and technology, but also with respect to the possible storage or reprocessing in Russia of US-origin spent nuclear fuel… In order for US-Russian nuclear cooperation to proceed, it is necessary for a bilateral agreement pursuant to section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act (a so-called “123 Agreement”) to enter into force. The Bush Administration submitted such an agreement to Congress for review on May 13, 2008. Many members of Congress have spoken out against this agreement because they believe it is premature to extend the benefits of nuclear cooperation with the United States to Russia so long as Russia is not doing more to contain the Iranian nuclear threat… Even if the agreement enters into force, however, the United States should condition the delivery to Russia of substantial financial benefits under this agreement (e.g., from the storage of US-origin spent nuclear fuel) on fuller diplomatic cooperation by Russia with regard to Iran…

Additionally, the next president should maintain a constant dialogue with Israel. US policymakers must recognise the grave and existential danger that the Islamic Republic poses to Israel. Believing its existence threatened, Israel could feel compelled to launch a strike to deny the Islamic Republic nuclear weapons capability… Only if Israeli policymakers believe that US and European policymakers will ensure that the Islamic Republic does not gain nuclear weapons will the Israelis be unlikely to strike Iran independently.

Leverage Building

To build additional leverage, states and international organisations should apply both unilateral and multilateral sanctions before and during any diplomatic rapprochement. These can be lifted as Iranian officials comply with their obligations. Such sanctions should include not only further broad UN Security Council resolutions, but also more targeted sanctions against Iran’s financial and energy sectors…

Fortunately, the next US administration has many financial tools at its disposal. The US Treasury Department’s quiet diplomacy with European banks should continue. Many European banks and companies have stepped back from operations in Iran when confronted with evidence of the Islamic Republic’s deceptive financial practices. Washington should press for expansion of sanctions upon Iran’s banking sector. Even without European acquiescence, the next occupant of the Oval Office should consider applying Section 311 of the USA Patriot Act to designate additional Iranian banks up to and including Bank Markazi, the central bank, because of their involvement in deceptive financial practices. Such action would, in effect, remove Iranian banks from the international financial stage…

Closing existing US and international sanction regime loopholes, through which Iran can procure technology and equipment for its energy sector is as important as utilising new financial tools against the Islamic Republic. For example, Washington should end the provision in US trade regulations that allows subsidiaries of US corporations to conduct relatively normal trade with Iran…

Another loophole… involves re-exportation of US goods. Under the 1995 US trade ban, knowingly re-exporting US goods to Iran is prohibited. Implementation, however, depends on enforcement, which has been lax, due at least in part to resource constraints. The Commerce Department should deploy a greater number of export control officers to well known hubs for re-export of US goods to Iran such as Dubai.

Diplomatic Engagement

Embarking upon a diplomatic solution with Iran will force a number of additional policy decisions. First, there is a question about what incentives the United States, Europe, and the international community will present to the Islamic Republic to encourage its compliance. We believe that the incentives already offered to Iran – an end to isolation, spare parts for its aging aircraft fleet, upgrades for its domestic oil and gas production, political cooperation – should remain part of any future package. Calibrating lifting of sanctions with Iranian compliance is another incentive, as are potential security guarantees and assurances. The president will need to balance any offer of new incentives with the knowledge that Iranian officials may see such offers as weakness to exploit. Both the Iranian regime and other potential proliferators may also interpret willingness to offer new incentives as rewards for Iran’s defiance.

Second, the new president will need to determine whether to maintain the policy of the Bush Administration and the EU-3 against negotiating with Teheran over the nuclear issue unless the Islamic Republic suspends its enrichment-related activities, or drop this precondition to negotiations. Any formal dialogue with Iran absent suspension of enrichment could backfire: Not only would the United States implicitly void all UN Security Council resolutions demanding a cessation of Iranian uranium enrichment, but Iranian authorities are likely to interpret US flexibility as acquiescence to the Iranian position that it must be permitted to enrich – all the more reason to increase multilateral sanctions as any new incentives are contemplated.

Should the new president decide, however, that the only way to test Teheran’s seriousness about resolving the nuclear dispute is to drop all preconditions to negotiation, several principles should be observed: First, the United States should only enter negotiation from a position of strength. This means that the United States must act in concert and with the full support of its allies. It must be able to show either that it and its allies have already ratcheted up economic pressure on Iran, or are prepared to do so in a meaningful manner should the Islamic Republic not agree to abandon its quest for nuclear weapons. Second, it must be clear that any US-Iranian talks will not be open-ended, but will be limited to a pre-determined time period so that Teheran does not try to ‘run out the clock’…

Direct negotiations with the Iranian regime can only succeed if we receive the cooperation needed by European allies, as well as key Persian Gulf countries, China and India.

If Diplomacy Does Not Succeed

Should diplomatic engagement not achieve its objectives within the set timeframe, the next president must turn to more intensive sanctions. While the most effective sanctions would target Iran’s oil and gas industries – Teheran’s chief source of income – the new president will need to balance the need for effective strategies with real world political and economic concerns about any action that would significantly impact the supply and price of oil. Some have proposed an embargo of gasoline exports to Iran but, in practice, there are too many suppliers to enforce fully without a blockade. However, even a partially effective embargo might have a psychological impact on the Iranian people, representing a cost for the Iranian leaders. An actual blockade of Iranian gasoline imports would have a much greater impact since, despite rationing, the Islamic Republic still must import about 25% of its refined petroleum needs, the majority of which enters Iran through sea ports. The Iranian regime feels vulnerable about its stability and a tighter rationing of gasoline or a spike in gasoline prices would likely spark further social discontent and political upheaval…

Should a blockade of gasoline imports not persuade Teheran, the next president would want to consider extending the blockade to Iran’s oil exports, thus cutting off the source of 80% of the government’s revenue. A blockade of Iran’s current two million barrels per day of oil exports would likely be the last sanction possible prior to an escalation into military action. It might prove crippling to the Iranian Government, but it could only be imposed for a very short period of time given the consequences it would have on the oil market, various net energy-importing countries and the global economy…

The Islamic Republic would almost certainly claim such blockades were acts of war, and would likely respond by attempting to destroy, either directly or by proxy, southern Iraq’s oil export facilities, which supply close to two million barrels per day for the global market… Iranian forces would also be expected to try to disrupt the passage of oil tankers through the Strait of Hormuz, through which 20% of the world’s oil transits.

Any blockade of Iranian energy imports or exports should be accompanied by a coordinated International Energy Agency announcement to release if necessary government strategic oil reserves…

The president would have to also coordinate any Western action to sanction or restrict Iran’s energy sector with senior leadership in Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf emirates to encourage those countries to pump more oil and store it in key consuming areas… Moreover, before it imposed any energy blockades on Iran, the US and its allies would have to first move sufficient military assets to the region in anticipation of kinetic action against Iran and in order to secure shipping lanes in the Strait of Hormuz.

Informational Campaign

Simultaneous to all such diplomatic and economic efforts must be a concerted informational campaign. Investment in Radio Farda and Voice of America should be increased multifold to a level commensurate with the strategic threat which the Islamic Republic now poses… We also recognise that while the Islamic Republic’s nuclear efforts pose a threat, the Iranian people are unfortunate victims of a situation over which they exert little or no control. It is in the long-term interests of the United States to see the far more moderate core of Iranian society increase its influence over their government. It is not the place of Washington to support any political groupings outside Iran or ethnic interests inside the country. However, the next president should recognise the importance of an independent civil society and trade union movement inside Iran and encourage their growth through any appropriate means.

Military Options

There are two aspects to the military option: boosting our diplomatic leverage leading up to and during negotiations, and preparing for kinetic action. For either objective, the United States will need to augment its military presence in the region. This should commence the first day the new president enters office, especially as the Islamic Republic and its proxies might seek to test the new administration. It would involve pre-positioning additional US and allied forces, deploying additional aircraft carrier battle groups and minesweepers, emplacing other war materiel in the region, including additional missile defence batteries, upgrading both regional facilities and allied militaries, and expanding strategic partnerships with countries north of Iran such as Azerbaijan and Georgia in order to maintain operational pressure from all directions.

While current deployments are placing a strain on US military assets, the presence of US troops in Iraq and Afghanistan offers distinct advantages in any possible confrontation with Iran. The United States can bring in troops and materiel to the region under the cover of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, thus maintaining a degree of strategic and tactical surprise… Some augmentation of US regional assets should be done overtly and publicly, to signal to the Iranians and to our regional allies American seriousness over the Iranian nuclear issue…

If all other approaches – diplomatic, economic, financial, non-kinetic – fail to produce the desired objective, the new president will have to weigh the risks of failure to set back Iran’s nuclear program sufficiently against the risks of a military strike. We believe a military strike is a feasible option and must remain a last resort to retard Iran’s nuclear development, even if it is unlikely to solve all our challenges and will certainly create new ones. Whether to pursue a military strike remains, of course, a political decision. When confronted with the possibility that the Islamic Republic may transition into a nuclear weapons state, the next administration might feel that the risks of a military strike are outweighed by the transformative dangers of living with a nuclear-armed Iran – such as dominance over the Persian Gulf region and its vast energy resources, a sustained spike in energy prices, nuclear proliferation throughout the Middle East, a radicalisation and possible destabilisation of the region, increased terrorist action in the region and beyond, possible provision of nuclear technology to other radical regimes and terrorists, and possible action to eradicate the State of Israel. We also understand that the nature of intelligence is that it seldom gives as full or as certain a picture as desired when it comes time to make a decision. No matter how much the next president may wish a military strike not be necessary, it is prudent that he begin augmenting the military lever, including continuing the contingency planning that we have to assume is already happening, from his first day in office.

A military strike would have to target not only Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, but also its conventional military infrastructure in order to suppress an Iranian response. However, it is important that any planning also occur simultaneously for the period immediately following, both providing food and medical assistance within Iran, as well as protecting regional allies from either direct or indirect Iranian response.

Military action against the Islamic Republic would incur significant risks, whether such action involves a limited air strike or a more sustained air and naval campaign such as the imposition of no-fly zones and a full blockade. Any military action would run the risk of significant US and allied losses, rallying Iranians around an unstable and ideologically extreme regime, triggering wide-scale Hezbollah and Hamas rocket attacks against Israel, and producing unrest in a number of the Persian Gulf states. An initial air campaign would likely last several days to several weeks and target both key military and nuclear installations… While a successful bombing campaign would retard Iranian nuclear development, Iran would undoubtedly retain its nuclear know-how. It would also require years of continued vigilance, both to strike previously undiscovered nuclear sites and to ensure that Iran does not resurrect its military nuclear program.

IV. Conclusion

It may be too late to keep Iran from becoming a nuclear power state, but it is not too late to prevent the Islamic Republic from becoming a nuclear weapons threat. There are no easy solutions. Any diplomatic solution requires a comprehensive strategy involving economic, military, and informational components undertaken in conjunction with allied and regional states. It is up to the government in Teheran to determine what travails the Iranian people must endure before such an agreement is made. The stakes are enormous. They involve not only US national security, but also regional peace and stability, energy security, the efficacy of multilateralism, and the preservation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty regime.

Any agreement, however, marks not the end of the crisis, but the beginning of a sustained phase for which the United States, its allies, and international agencies must also prepare. Iranian compliance with its commitments must be verifiable, and any Iranian nuclear activity must be monitored comprehensively and in real time, not just by periodic inspections. Iran is an important country and we would welcome its return to the international community if its government adheres to its international obligations.

Tags: International Security