Australia/Israel Review

Essay: The Great Divide

Sep 1, 2007 | Gal Luft and Anne Korin

Sunnis, Shi’ites and the West

By Gal Luft and Anne Korin

The attacks of 9/11 generated a tide of commentary on the origins and aims of anti-Western jihadism. Lately, however, events have shifted attention to another, more long-standing feature of the Muslim world, raising the question of whether Islamic militancy against the West is now of lesser geopolitical significance than a stark, increasingly salient divide within Islam itself. This is the ancient divide between the numerically dominant Sunnis and a Shi’ite minority that is finally coming into its own.

In this, as in so much else, the prime exhibit is Iraq. Since the country changed hands from a Sunni dictatorship to a Shi’ite-controlled government, the conflict there, at first slowly but then with growing intensity, has at least in part taken on the appearance of a war between two sects. Every week brings gruesome suicide attacks on Shi’ites by Sunni terrorists, attacks answered in kind by Shi’ite militias or death squads. Iraqis have been dragged from their cars and killed merely for being Sunni or Shi’ite. Whole neighbourhoods of Baghdad have been emptied of one sect or the other. Mortar attacks have been launched from cemeteries and shrines, and the holiest of mosques have been bombed and torched by putative co-religionists.

American policymakers have seemed stymied by this outburst of Sunni-Shi’ite hatred, and especially by the assertiveness of the Shi’ites. Not only does it challenge a familiar conception of the order of things in the Middle East – an order ostensibly based on the leadership of longtime “moderate” Sunni allies like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan – but it coincides with the mounting aggressiveness of Shi’ite Iran, which aspires to regional hegemony. From Iraq to Lebanon, from Pakistan to the streets of Amman, the delicate fabric of a centuries-old pattern is being torn.

The schism between Sunnis and Shi’ites is real enough. It dates back to the 7th century CE, when the succession to Muhammad, Islam’s prophet, was denied to his son-in-law Ali and given instead to his friend Abu Bakr, who became the first caliph. Supporters of the bypassed Ali – the ancestors of today’s Shi’ites – sided with his son Hussein in the hopeless battle of Karbala in 680, whose victors solidified the rule of the Umayyad dynasty over the lands of Islam. Since then, Shi’ites, who now make up a mere 10% of Islam’s 1.5 billion believers worldwide, have been a disenfranchised lot, often treated as heretics even in those countries, like Iraq, where they have in fact formed a majority.

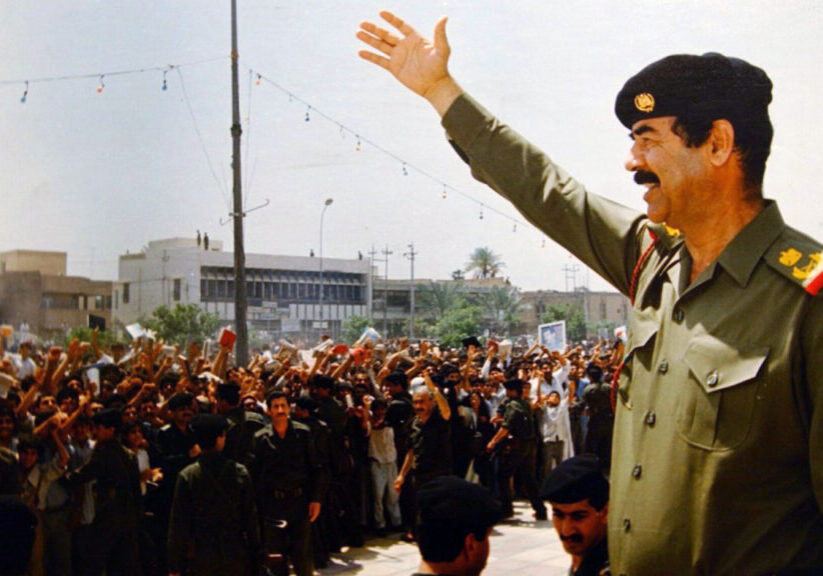

For many Shi’ites worldwide, the moment to rectify this historical injustice finally arrived 13 centuries later, in 1979, when Ayatollah Khomeini seized power in Iran. For their part, the region’s Sunni oil monarchies responded to the new threat by huddling together to establish the Gulf Cooperation Council, an Arab version of NATO. In Iraq, the Sunni Baathist dictator Saddam Hussein chose a more vigorous route; he attacked Iran frontally, sparking an eight-year war in which more than a million Muslims on both sides lost their lives. Continuing his anti-Shi’ite campaign in the early 1990s after the first Gulf war, Saddam killed several hundred thousand more of his own Shi’ite subjects, devastating the southern reaches of Iraq. Only after the second Gulf war, in 2003, did Iraqi Shi’ites finally win a measure of political control proportionate to their estimated 60% of the country’s population.

In the early years of the American occupation of Iraq, Shi’ites showed remarkable self-restraint, especially in light of the fearful oppression they had suffered at the hands of Saddam Hussein and the murderous campaign waged after his downfall by the Baathist insurgency. Shi’ite moderation evaporated, however, after the February 2006 bombing of the Askariya Mosque in Samarra, one of the sect’s holiest shrines. Leading Iraqi Shi’ites are now candid in describing the present moment as a turning point in Muslim history, and declare openly that they have no intention of surrendering their gains. One of the country’s most influential Shi’ite groups, the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (recently renamed the Supreme Islamic Iraqi Council), has from time to time enunciated its aim of exporting Shi’ite empowerment to the rest of the Middle East as well.

In a number of places, Shi’ite groups have already demonstrated their new self-assertiveness. In Lebanon, where Shi’ites comprise 45% of the population, Hezbollah – the Islamist movement founded and supported by Iran – has been emboldened by its supposed “divine victory” over Israel last summer. Led by the charismatic Hassan Nasrallah, the group has challenged the legitimacy of the government of Prime Minister Fouad Siniora – a Sunni – and staged massive street protests under the banner of Shi’ite supremacy. In Yemen, a mini civil war is taking place between the Sunni-dominated authorities and the Believing Youth movement, a Shi’ite group that aims to replace the government with a clerical regime.

In Pakistan, a Sunni country with a minority of more than 40 million Shi’ites, inter-communal conflict killed more than 300 people in 2006. This year, tension mounted during the Shi’ite religious festival of Ashura after Sunnis fired rockets at a Shi’ite mosque and two suicide bombers detonated explosives near Shi’ite gatherings.

Throughout the region, Sunni authorities are eyeing their Shi’ite citizens with suspicion and alarm. In Algeria, a dozen teachers were arrested on the charge of spreading Shi’ite propaganda among their pupils. In Sudan, where there is talk of a “Shi’ite peril”, Arab Sunni Islamists have accused “Persians” of spreading heresies. Anti-Iranian fear has spread to Bahrain, the home base of the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet; in February, clashes broke out there between Shi’ite protesters and the Sunni-dominated security forces.

Anti-Shi’ite sentiment is prevalent even in places where few Shi’ites exist. In the overwhelmingly Sunni Gaza Strip, for example, Fatah supporters chant “Shi’ite” at Hamas because of that Islamist group’s close ties with Iran. Jordanians blame the Shi’ites who have won control of the government in Baghdad for the Sunni refugees who have flooded into their own country, and Jordan’s King Abdullah has warned of an emerging “Shi’ite crescent” stretching from Beirut to Teheran. In Egypt, Sheikh Yousuf al-Qaradawi, one of the most influential Sunni clerics, has warned that “Shi’ite infiltration of Egypt will ignite a blaze that will destroy everything in its path.” For his part, President Hosni Mubarak fanned the flames of intra-Muslim hostility last year by proclaiming that “Most Shi’ites are loyal to Iran and not to the countries they are living in.”

Beyond questions of political and religious authority, the conflict between Sunnis and Shi’ites has a strong bearing on control of the world’s economic lifeblood – Arabian crude oil. Whatever the disproportionate weight of Sunnis in the Muslim world as a whole, in the oil-rich Persian Gulf, Shi’ites comprise a 70% majority. As if by divine plan, 45% of the world’s proven oil reserves lie under territories inhabited by the “sons of Ali”. These territories include Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and (most important of all) the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, home to most of the kingdom’s giant oil fields and export terminals.

For the Saudi royal family, the prospect of a Shi’ite uprising is a nightmare. Shi’ites make up roughly 15% of Saudi Arabia’s population of 25 million. Most Saudis, practitioners of the extremist Wahhabi sect of Sunni Islam, see these Shi’ites as heretics who should be treated as second-class citizens or, in the words of one cleric, as “more dangerous than Jews and Christians.” For their part, Saudi Shi’ites see themselves not only as an oppressed minority, but as an occupied one. They sit atop the country’s oil but enjoy none of its rewards, and their appetite for political power has been whetted by the Shi’ite revival in Iraq. To the alarm of the House of Saud, during the 2005 Saudi municipal elections, turnout in Shi’ite-dominated regions was twice as high as it was elsewhere.

Though Saudi Shi’ites are still relatively docile, they have a history of restiveness of which the Saudi regime is acutely aware. In the wake of Iran’s revolution in 1979, Shi’ite militants in Saudi Arabia mounted an uprising that resulted in scores of deaths. Later, when Iran seemed to gain the upper hand in its long war with Iraq, Shi’ite groups bombed Saudi energy facilities. Today, in an exceedingly tight international oil market, a Shi’ite uprising could wreak havoc.

Oil is not the only problem. Another byproduct of the Sunni-Shi’ite divide is that the feeble Sunni Gulf monarchies have become arms-crazed as never before. Awash in petrodollars, and fearing the rise of Shi’ite Iran, they have embarked on a military shopping spree, acquiring top-of-the-line fighter aircraft, cruise missiles, attack helicopters, missile-defence batteries, and hundreds of modern tanks, at a total cost of over US$60 billion in 2006 alone. Much of this arms race is fuelled by the suspicion that, if the Iranian Revolutionary Guards decided to cross the border, the US might not ride to the rescue as it has done in the case of previous threats.

Even more ominously, with Iran intent on becoming a nuclear power, the race among the Sunni Arab states to acquire nuclear capabilities has already begun. During its December meeting, the six-member Gulf Cooperation Council decided to embark on a joint nuclear program for “peaceful purposes”. Two weeks later, Yemen announced its aspirations for nuclear technology, and Jordan followed soon thereafter. Similar declarations have been heard from Morocco, Algeria, and Egypt. President Hosni Mubarak drew roaring applause when he announced in a November speech that Egypt was not “in need of anyone’s authorisation to develop peaceful nuclear energy.” Like Shi’ite Iran, the Sunni Arab countries assure the world that their programs are for economic and scientific benefit only, but in the Middle East, “peaceful nuclear program” is an oxymoron.

In this connection, it should be noted that the Sunni states have never felt the need to accelerate their nuclear programs in the face of Israel’s presumed nuclear dominance. Much as the Arabs might hate the Jewish state, they have counted on its composure and predictability; even with their backs against the wall, Israel’s leaders have never pushed the nuclear button. Evidently, the Sunnis are nowhere near so confident about the mullahs in Teheran, and have begun to lay their plans accordingly.

It is possible, of course, to exaggerate the seriousness of the sectarian rift in the Islamic world. The Sunni-Shi’ite divide is just one of many layers of complexity in the complex Middle East. History shows that even the most bitter doctrinal differences can be and have been put aside, especially when confronting common enemies. Thus, Sunnis and Shi’ites fought together in the 1920 rebellion against British rule in the region, and more recently have occasionally joined forces to oppose the Americans in Iraq. Whatever a regime’s particular religious colouration, moreover, neither group has refrained from oppressing or turning viciously on its own sectarian kith and kin to suit the demands of need or convenience.

Nor is that all. We are speaking of communities that number in the hundreds of millions, who are far from being an undifferentiated mass. Even though the voices of the reformers in their midst may be muted by political intimidation from state or clergy, it would be wrong to assume that America’s democratising intervention will not bear fruit, or that the future inevitably belongs to the Islamist sectarians and political extremists now committing or threatening mayhem. In Iraq, a figure like Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani still commands greater mass respect and loyalty than Moqtada al-Sadr and his ilk. Thanks to him and others on both sides, it is hardly inconceivable that Sunnis may yet reconcile themselves to the newly prominent place of Shi’ites in that country, and that Shi’ites will learn to wield their new power responsibly. Politics, in other words, counts a very great deal.

Still, however one measures the danger of the Sunni-Shi’ite conflict, there is no denying its present reality or the need to take it into account in Western foreign-policy planning. What can we do about it?

One recommended course has been to assume the role of a detached spectator – that is, to do nothing, allowing Islam’s internecine struggle to take its toll. Proponents of such a policy argue that the West has lost its ability to influence internal developments in the Muslim world, and should just let sectarian passions burn themselves out. Others see a blessing in internal strife, believing that it redounds to our advantage by diverting and overshadowing Muslim grievances against the West.

The problem with this approach is that, if weapons of mass destruction and oil shocks become commonplace in the region, the developed nations of the West are as likely to suffer the consequences as are the people of the Middle East. Masses of poor refugees could destabilise emerging democracies in the region, reverse political reforms, and give a boost to the jihadist movement, which thrives on oppression and disgruntlement. The growing potential for bloodshed and humanitarian catastrophe also creates a moral imperative, one that the US, having involved itself so deeply in the region, would find hard to ignore.

Another option is to pick a favourite. This is clearly what at least some elements in the Bush Administration seem to be leaning toward. Increasingly disenchanted with Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, and intent on containing Iran, they have begun to speak of a new strategic alignment in the Middle East, arraying “moderate” Sunni allies like Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, and the Gulf states against the Shi’ite “extremists” of Iran, Syria, and Hezbollah.

Evidence for this shift in thinking lies in Washington’s rising regard for Saudi Arabia. Just five years after September 11, an attack perpetrated in large part by Saudi nationals, the US appears to be outsourcing parts of its Middle East policy to the House of Saud, bolstering the kingdom’s military capabilities and, according to reports, involving itself in clandestine operations with radical Saudi proxies who loathe America but happen to hate the Shi’ites even more. As Patrick Clawson of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy told the New Yorker, “At a time when America’s standing in the Middle East is extremely low, the Saudis are actually embracing us. We should count our blessings.”

But these “blessings” are themselves decidedly mixed, as the Bush White House itself has long recognised. Though Saudi diplomats, presumably with American approval, are newly engaged in regional diplomacy, the deal they brokered in Mecca in February to create a Palestinian unity government did less than nothing to advance the cause of peace in the Middle East. In the Palestinian Authority, Hamas remains in command, and continues to repudiate the Jewish state’s right to exist. Two months after the Mecca meeting, moreover, Foreign Minister Saud al-Faisal warned at the Arab summit in Riyadh that rejection of Saudi Arabia’s all-or-nothing “peace plan” would leave Israel’s fate in the hands of the “lords of war”. And in the meantime, Saudi Arabia continues to support Wahhabist educational institutions throughout the world and to fund Sunni extremists, including those responsible for most American casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan.

An alignment with supposed Sunni “moderates” is, in short, a huge gamble. Essentially it would perpetuate, or resurrect, the same Sunni order that has been responsible over the course of several generations for most of the Middle East’s pathologies. It is under the Sunni dispensation, after all, that the Arab world has lagged in every dimension of human development, from political and cultural freedom to economic growth, while simultaneously giving birth to a virulent Islamic radicalism. Were it not for a massive infusion of petrodollars, and the occasional protection afforded by American arms, the old Sunni order would have collapsed some time ago. Our propensity to preserve it now is based on inertia – it is the devil we know – not on merit or performance.

No less importantly, renewed support of the Sunni establishment constitutes a gross departure from the effort after 9/11 to leave behind the counterproductive cynicism of foreign-policy realpolitik. As President Bush declared two years ago:

The policy in the past used to be, ‘Let’s just accept tyranny, for the sake of… cheap oil, or whatever it may be, and just hope everything would be okay.’ Well, that changed on September the 11th for our nation. Everything wasn’t okay. Beneath what appeared to be a placid surface lurked an ideology based upon hatred.

Now, unfortunately, the need for cooperation from openly autocratic and repressive regimes seems to have temporarily pushed aside the administration’s emphasis on promoting liberalisation and democracy in the region.

This brings us to a third option, the one that the Bush Administration in its more considered moments has seemed resolved upon – namely, to encourage the establishment of a constructive and sustainable Sunni-Shi’ite balance of power in the Middle East. Ideally, a Shi’ite bloc, led by a reformed Iran, could offer a counterbalance to the dysfunctional Sunni order that for too long has held our loyalty, with costs that we only fully realised on 9/11. Under this scheme, Iranian business acumen and worldliness, liberated from the deadly grip of the ayatollahs, might well prove to be the elixir that the Middle East sorely needs. Should human development in the Shi’ite bloc show results – in education, economic progress, and cultural achievement – the region’s Sunnis would feel spurred to compete, if for no other reason than to maintain their dignity within the Muslim world.

The positive aspect of this agenda might well sound Pollyanna-ish; but immediate steps could help bring it closer to realisation. Those steps amount to continuing our fight against the radical elements within both blocs, from al-Qaeda and its Saudi backers to the newly energised Islamic revolutionaries in Teheran. The spread of Islamic ideology is a threat to Western security, and must be confronted and combated regardless of who spreads it. By defining moral and strategic red lines, and by applying them across the board, the US would be in a position to denounce Wahhabi bigotry and Iranian sabre-rattling with equal vigour – especially if it were willing to run the risk of paying a few dollars more at the gas station in order to demonstrate its seriousness.

Reciprocally, the leaders of the Muslim world, especially those who receive generous American aid, would be required to demonstrate their own seriousness, in the first place by ending their silence and apathy in the face of internecine slaughter. In the Sunni world, as the columnist Ralph Peters has observed, “Shi’ites only count for Muslims when America can be blamed for their suffering.” Evidence of Sunni bona fides should be sought in the willingness of Hosni Mubarak and King Abdullah to repudiate the slaughter of Iraqi Shi’ites with the same energy they habitually commit to blasting Israel’s self-defensive measures against the terrorists of Hamas and Islamic Jihad.

The same sort of American even-handedness is needed on nuclear proliferation. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, with his apocalyptic rhetoric and nationalistic swagger, richly deserves his place atop the list of current threats to global security. But elements no less dangerous are hatching in the Sunni world. Sometime in the next decade, a Taliban-style regime, flush with petrodollars and cosy with al-Qaeda, could conceivably take over Saudi Arabia, Egypt, or Pakistan, seizing control of nuclear capabilities that are currently being nurtured under the West’s unwatchful eyes. In light of this prospect, it is shortsighted indeed for us to be providing scientific nuclear assistance to “allies” like Egypt. In the end, the US might not be able to reverse the nuclear momentum in the Middle East; but, at a minimum, no smaller price for pursuing it should be exacted from Sunnis than from Shi’ites.

The current strategic situation in the Middle East offers no particularly good options. To the extent that there is a way out, it can be charted only by Muslims themselves, of their own volition and at their own pace. In this respect the situation bears some similarity to the one facing Christendom centuries ago, when Europe tore itself apart in a long series of religious wars. Like the warring factions in post-Saddam Iraq, Europe’s Christians fought each other for political control and in the name of what they saw as the true faith. This dark period drew to an end only in 1648, with an international conference at which the exhausted nations agreed to a new order. The Peace of Westphalia began the gradual extraction of religion from European politics.

One can only hope that the bloody internal struggle within Islam will deliver similar results more quickly. As yet, no Muslim Martin Luther is in sight, and those advocating either a live-and-let-live acceptance of denominational differences or the legitimacy of secularism face a bitter uphill struggle. It is likely to take decades before Sunnis and Shi’ites reach any kind of stable accommodation, if they manage at all.

In the meantime, the US and its allies must recognise that, unlike in the case of the Eighty Years’ War and the Thirty Years’ War, which were hardly felt outside of Europe, the convulsions created by the Sunni-Shi’ite divide will reverberate throughout the world. If the West is to have any role in encouraging a Muslim reformation, it will be through the consistent application of our principles, holding both Shi’ites and Sunnis to the same standard, as much as by the ruthless pursuit of those of either creed who would do us harm.

And this, of course, highlights once again the crucial importance of success in Iraq, the current vortex of both regional and inter-denominational strife. A decent resolution of that conflict will hasten the reform and modernisation of other nations, Sunni and Shi’ite alike. If our project there fails, whether from Arab indifference and incapacity or a lack of Western resolve, the resulting civil war could feed the flames of both intra- and extra-Islamic conflict on a global scale.

![]()

Dr. Gal Luft is Executive Director of the Washington, DC-based Institute for the Analysis of Global Security (IAGS). Anne Korin is Director of Policy and Strategic Planning at IAGS and the Editor of Energy Security. © Commentary, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iraq