Australia/Israel Review

Essay: How to win in Afghanistan

Oct 27, 2009 | Max Boot

By Max Boot

The terms counterterrorism and counterinsurgency have become common currency this decade in the wake of September 11, the invasion of Afghanistan, and the war in Iraq. To a layman’s ear, they can sound like synonyms, especially because of our habit of labelling all insurgents as terrorists. But to military professionals, they are two very different concepts. Counterterrorism refers to operations employing small numbers of Special Operations “door kickers” and high-tech weapons systems such as Predator drones and cruise missiles. Such operations are designed to capture or kill a small number of “high-value targets”. Counterinsurgency, known as COIN in military argot, is much more ambitious. According to official US Army doctrine, COIN refers to “those military, paramilitary, political, economic, psychological, and civic actions taken by a government to defeat insurgency.” The combined approach typically requires a substantial commitment of ground troops for an extended period of time.

When General Stanley McChrystal was selected on May 11 of this year as the American and NATO commander in Afghanistan, it was by no means certain which approach he would employ. His background is almost entirely in counterterrorism. He had been head of the Joint Special Operations Command (comprising elite units such as the Army’s Delta Force and the Navy’s SEALs) when it was carrying out daring raids to capture Saddam Hussein and kill Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq. If he had decided to follow the same approach in Afghanistan, he would have had the support of US Vice President Joe Biden and numerous congressional Democrats who favour a narrow counterterrorism strategy to fight al-Qaeda and who want to cut the number of American troops to a bare minimum.

But that is not what McChrystal has chosen to do. He has decided, as he put it in an “interim assessment” dated Aug. 30 (later leaked to Bob Woodward of the Washington Post) that “success demands a comprehensive counterinsurgency (COIN) campaign.” A close reading of that document, which was directed at the Pentagon and White House, as well as the “Counterinsurgency Guidance” drafted at his behest around the same time and directed at his own troops, provides a window into his thinking. It shows why a COIN campaign is needed, how it would be carried out, and why the kind of narrow counterterrorism effort favoured by so many amateur military strategists is unlikely to succeed.

The case against a counterterrorism approach in Afghanistan is laid out most clearly in the Counterinsurgency Guidance. McChrystal’s focus is on explaining why conventional military operations cannot defeat the insurgency in Afghanistan, but the same arguments apply to counterterrorism generally, which is a smaller-scale version of the same conceit – that the US military can defeat an insurgency simply by killing insurgents. McChrystal writes that the math doesn’t add up:

From a conventional standpoint, the killing of two insurgents in a group of ten leaves eight remaining: 10 - 2 = 8. From the insurgent standpoint, those two killed were likely related to many others who will want vengeance. If civilian casualties occurred, that number will be much higher. Therefore, the death of two creates more willing recruits: 10 minus 2 equals 20 (or more) rather than 8.

He goes on to note that the “attrition” approach has been employed in Afghanistan over the past eight years by a relatively small number of American forces and their NATO allies. Yet, he writes, “eight years of individually successful kinetic operations have resulted in more violence.” He continues: “This is not to say that we should avoid a fight, but to win we need to do much more than simply kill or capture militants.”

What else, then, must coalition forces do? McChrystal’s answer:

An effective “offensive” operation in counterinsurgency is one that takes from the insurgent what he cannot afford to lose – control of the population. We must think of offensive operations not simply as those that target militants, but ones that earn the trust and support of the people while denying influence and access to the insurgents.

The Counterinsurgency Guidance points out that firing guns and missiles can often make it more difficult to win “trust and support”. An anecdote makes the point:

An ISAF [International Security Assistance Force] patrol was traveling through a city at a high rate of speed, driving down the Centre to force traffic off the road. Several pedestrians and other vehicles were pushed out of the way. A vehicle approached from the side into the traffic circle. The gunner fired a pen flare at it, which entered the vehicle and caught the interior on fire. As the ISAF patrol sped away, Afghans crowded around the car. How many insurgents did the patrol make that day?

McChrystal counsels his troops to take a different path, to “embrace the people,” to “partner with the ANSF [Afghan National Security Forces] at all echelons,” and to “build governance capacity and accountability.” He urges coalition troops to be “a positive force in the community; shield the people from harm; foster stability. Use local economic initiatives to increase employment and give young men alternatives to insurgency.”

This would mean putting less emphasis not only on using force but also on “force protection” measures (such as body armour and heavily armoured vehicles), which distance the security forces from the population. As an example of what he expects, McChrystal cites an anecdote involving an “ISAF unit and their partnered Afghan company” that were “participating in a large shura [tribal council] in a previously hostile village.” During the shura, which was attended by “nearly the entire village,” he writes, “two insurgents began firing shots at one of the unit’s observation posts.” The sergeant in charge of the post could have returned fire but he chose not “to over-react and ruin the meeting.” “Later,” this example concludes, “the village elders found the two militants and punished them accordingly.”

While counterintuitive to a conventional military mind, such thinking is hardly novel for anyone familiar with the history of counterinsurgency. McChrystal’s advice to embrace the population and be sparing in the use of firepower has been employed by successful counterinsurgents from the American Army in the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century; to the British in Malaya in the 1950s and Northern Ireland from the 1970s to the 1990s; to, more recently, the Americans in Iraq. By contrast, counterinsurgency strategies that rely on firepower have usually failed, whether tried by the French in Algeria, by the US in Vietnam, or by the Russians in Afghanistan.

The risk of the counterinsurgency approach – which helps to explain why it has not been adopted in Afghanistan until now or in Iraq until 2007 – is that, in the short term, it will result in more casualties for coalition forces. Placing troops among the people and limiting their expenditure of firepower makes them more vulnerable at first than if they were sequestered on heavily fortified bases and ventured out only in heavily armoured convoys. But in the long term, as the experience of Iraq shows, getting troops off their massive bases is the surest way to pacify the country and bring down casualties.

Unfortunately, the NATO force that McChrystal now commands, the ISAF, has been failing for years to carry out the tenets of sound counterinsurgency policy owing to a lack of willpower and a lack of resources. Instead, it has combined conventional and counterterrorist strategies in an ill-coordinated and incoherent mishmash. McChrystal’s Initial Assessment is withering in its description of the ISAF as “poorly configured… inexperienced in local languages and cultures, and struggling with challenges inherent to coalition warfare.” The result has been parlous:

Preoccupied with protection of our own forces, we have operated in a manner that distances us – physically and psychologically – from the people we seek to protect. In addition, we run the risk of strategic defeat by pursuing tactical wins that cause civilian casualties or unnecessary collateral damage.

To turn around a “deteriorating” situation, McChrystal has proposed major changes in both doctrine and organisation. Some of the organisational changes are already under way. The most prominent of these is the creation of a new three-star headquarters known as the ISAF Joint Command, which will be run initially by Lt.-Gen. David Rodriguez, a former commander of the 82nd Airborne Division. The creation of this new layer of command is based on the example of Iraq, where, in 2007, Gen. David Petraeus was in charge of overall policy, but Lt.-Gen. Ray Odierno was in charge of day-to-day operations.

In Afghanistan there has been no equivalent to Odierno, and therefore a notable lack of coherence and coordination in operations. For instance, the McChrystal report notes that counternarcotics efforts “were not fully integrated into the counterinsurgency campaign.” That is something that Rodriguez, whose headquarters will be fully operational in early November, will have to fix – along with a host of other tasks that will be outlined in a confidential and detailed “joint campaign plan”.

Another part of the ongoing reorganisation proposes to consolidate disparate training efforts undertaken by numerous nations under a new organisation called NATO Training Mission – Afghanistan. It will be given the goal of expanding the Afghan security forces much more rapidly – growing the army from 92,000 to 240,000, and the national police from 84,000 to 160,000.

Changing organisational flow charts is relatively easy. So too is redeploying troops from sparsely populated rural areas to the areas where the population is concentrated – another major tenet of “population-centric” counterinsurgency. Much harder will be changing minds, especially those of American allies who have little familiarity with, or interest in, the kinds of manpower-intensive counterinsurgency practices that US forces learned to employ in Iraq.

Harder still will be improving the quality of Afghan governance so that, in the words of the McChrystal report, “a stronger Afghan government … is seen by the Afghan people as working in their interests.” The presidential election held on Aug. 20, 2009, which was marred by widespread fraud, does not make the task any easier, but it is hardly impossible. Even if the current president, Hamid Karzai, finally emerges victorious, this does not mean that the Afghan people will have to remain alienated from their government. Karzai remains fairly popular, especially in the Pashtun areas where the insurgency is based; he likely would have emerged as the top vote getter in a completely fair election.

Whoever ends up as president, NATO forces will have to work with the United Nations, various nongovernmental organisations, and civilian government agencies such as the US State Department to fight corruption and improve the delivery of basic services such as clean water, paved roads, electricity, education, and a functioning legal system. Ultimately, the people of Afghanistan will judge the quality of their government by what it delivers, not how it was set up. Moreover, for the purposes of the overall effort in the country, the Afghan government does not have to be perfect; it only has to be better than the Taliban’s “shadow government.”

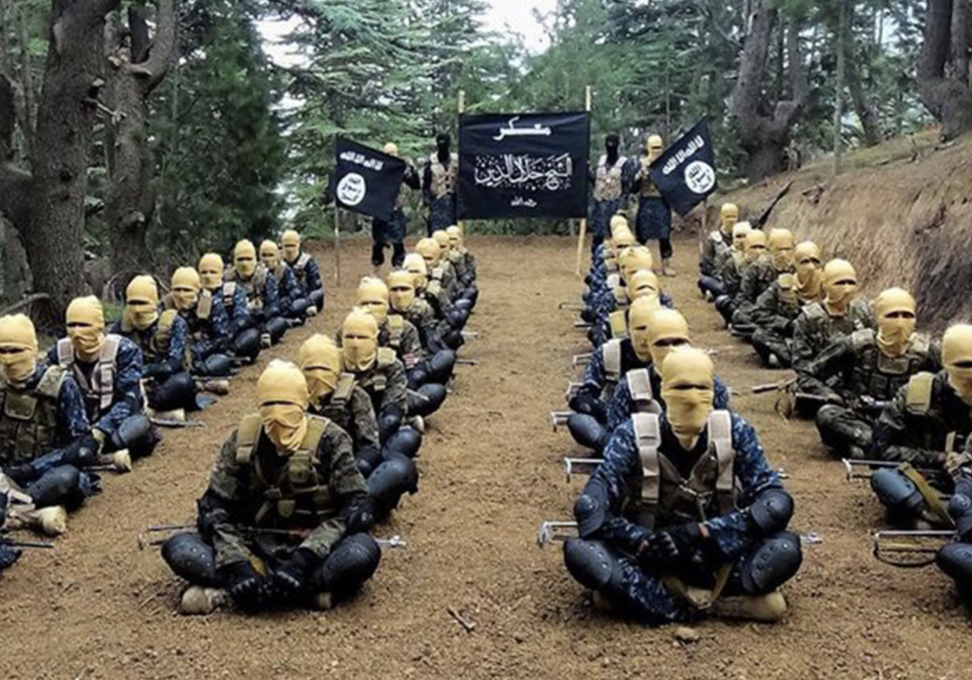

In trying to achieve these tasks, McChrystal will face a challenge commanders did not confront on the same scale in Iraq – cross-border havens. If there has been one consistent means of enabling insurgent success, from the mujahedeen fighting the Russians in the 1980s to the Vietcong fighting the French in the 1950s and the Americans in the 1960s, it has been the ability to set up secure sanctuaries for recruitment, training, and equipping. This has been a small but significant issue in Iraq, where insurgents continue to receive support from Syria and Iran. The problem is much more acute in Afghanistan, which shares a porous 2,600-kilometre border with Pakistan.

Some have suggested that the involvement of Pakistan makes a favourable outcome in Afghanistan a long shot. McChrystal disagrees. He writes that “Afghanistan does require Pakistani cooperation and action against violent militancy,” but he also notes that the “insurgency in Afghanistan is predominantly Afghan.”

He might have added, but didn’t, that those who say Pakistan is the “real problem” don’t offer any idea of how to improve the situation in Pakistan if we pull back in, or move out of, Afghanistan. An American scuttle from Afghanistan (which is how a transition to a counterterrorism strategy would be perceived) would simply encourage Pakistan to go back to its old strategy of allying itself with jihadist groups, because it would be convinced that the US was not a reliable partner.

To carry out his strategy, McChrystal must have more resources, especially more troops. In his assessment, he writes, “Resources will not win this war, but under-resourcing could lose it.” NATO’s war effort has in fact been under-resourced for years, “operating in a culture of poverty,” as McChrystal puts it. That has made it impossible to carry out classic counterinsurgency operations, because those typically require a ratio of roughly one counterinsurgent per 50 civilians. Given Afghanistan’s population of 30 million, 600,000 counterinsurgents would be necessary. At the moment, the total is roughly 270,000 (170,000 Afghans, 64,000 Americans, 35,000 from other nations). Actual force planning, however, is too intricate to be reduced to such back-of-the-envelope calculations. Unique local characteristics have to be taken into account, such as the fact that the insurgency is largely confined to the Pashtun, an ethnic group that comprises 42% of the population.

McChrystal and his staff have drawn up a range of recommendations on extra troop levels. The respected military analysts Frederick and Kimberly Kagan, who have consulted for McChrystal, have completed a study of their own that suggests a need for 40,000 to 45,000 additional troops, to be concentrated in eastern and southern Afghanistan. Such a number is reportedly at the high end of what McChrystal has recommended, but in war it’s always better to have too many troops than too few.

Too few, however, is what he may get. After repeatedly pledging he would “make the fight against al Qaeda and the Taliban the top priority that it should be,” US President Barack Obama seemed to have gotten cold feet in early September. With casualties rising and public support falling, he delayed action on McChrystal’s Initial Assessment and told the general not to bother submitting his resource requirements until a new strategic review had been completed. That review will arrive just six months after the last administration review, completed in March, which led to the dispatch of 21,000 troops to Afghanistan as part of what Obama described as a “comprehensive new strategy for Afghanistan and Pakistan.”

Those who oppose sending more troops suggest that trying to fight and win in the supposed “graveyard of empires” is a hopeless undertaking. Sceptics argue that Afghanistan is so backward, feudal, and militaristic that no foreign army has any chance of prevailing no matter what strategy it uses. Some go so far as to assert that Afghanistan is not a “real” country, and that brutish warfare is its natural state. This is a gross misreading of history. It’s certainly true that Afghanistan is a tribal society and that it has always been fairly decentralised. But it has also been a state since the 18th century and has been governed by strong rulers such as Dost Muhammad, who ruled from 1826 to 1863.

The country was actually relatively peaceful and prosperous before a Marxist coup in 1978, followed by a Soviet invasion the next year, triggered turmoil that still has not subsided.

But isn’t it the case that Afghans have always rejected all outside military intervention? The two most commonly cited examples in support of this proposition are the British in the 19th century and the Russians in the 1980s. This selective history conveniently omits the military success enjoyed by earlier conquerors, from Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE to Babur (founder of the Mughal Empire) in the 16th century.

In any case, neither the British nor the Russians ever employed proper counterinsurgency tactics. Neither empire had popular support on its side, as foreign forces do today. In recent polling, only four percent of Afghans express a desire to see the Taliban return to power. Sixty-two percent have a positive impression of the United States, and 82 percent have a favourable view of our chief on-the-ground ally – the Afghan National Army.

Perhaps, despite everything, the sceptics are right – maybe it is impossible to deploy a successful counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan. But it is hard to know why Afghanistan would be uniquely resistant to methods and tactics that have worked in countries as disparate as Malaya, El Salvador, and Iraq. Indeed, after a study of 66 20th century insurgencies in which a foreign power committed significant resources to the fight, political scientists Andrew J. Enterline and Joseph Magagnoli found that population-centric strategies succeeded 75 percent of the time.

What we have tried is the other strategy, the counterterrorism strategy, and it has been found wanting. This should not come as a surprise, because it is hard to point to any place where pure CT has defeated a determined terrorist or guerrilla group.

Vice President Biden may think that a few long-range strikes will prevent terrorist sanctuaries from emerging in Afghanistan. Gen. McChrystal, who knows a thing or two about the CT business, has concluded otherwise. Which man, one wonders, will the president listen to? He doesn’t have long to decide, because as McChrystal writes, “Failure to gain the initiative and reverse insurgent momentum in the near term (next 12 months)… risks an outcome where defeating the insurgency is no longer possible” – and an outcome in which the United States and its allies find themselves experiencing a devastating and unnecessary defeat in a conflict that President Obama himself has described as a “war of necessity”.

Max Boot is the Jeane J. Kirkpatrick Senior Fellow in National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations and author, most recently, of War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History, 1500 to Today. He is writing a history of guerrilla warfare and terrorism and has traveled to Afghanistan twice this year. © Commentary magazine, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Afghanistan/ Pakistan