Australia/Israel Review

Editorial: What kind of sanctions?

Mar 1, 2010 | Colin Rubenstein

Colin Rubenstein

Mohammed ElBaradei, as director general of the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), was awarded the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize for “efforts to prevent nuclear energy from being used for military purposes.”

This is ironic, because it is now apparent that ElBaradei held back evidence which showed Iran was pursuing nuclear energy for precisely such purposes.

After years of reports denying there was evidence of Iranian militarisation of its nuclear program, the most recent IAEA report, declares “the Agency would also like to discuss with Iran: the project and management structure of alleged activities related to nuclear explosives… [and] details relating to the manufacture of components for high explosives initiation systems…” strongly implying there is evidence Iran is working on nuclear weapons designs.

That the new IAEA report has teeth is not due to startling new evidence emerging from Iran but apparently due to ElBaradei having stepped down.

His replacement is Yukiya Amano, a well-regarded Japanese public servant. First impressions indicate Amano seems determined to concentrate on the pimary obligations of his office, which are to issue reports on the compliance or otherwise of IAEA member states, but not to pontificate on these matters. ElBaradei often did – making no secret of his belief that all pressure, including sanctions, against Iran must be avoided and, according to leaks from inside the IAEA, he pressured the agency’s technical experts not to include in their reports any information or analysis that might undermine this agenda.

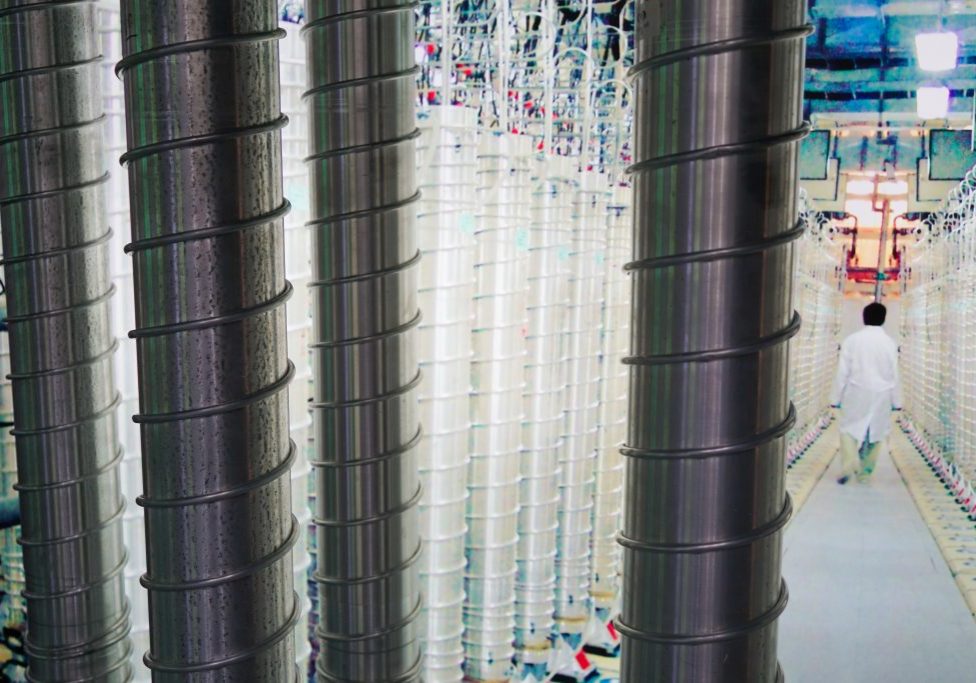

The new report holds good and bad news regarding Iran. It acknowledged the trouble Iran is having in the uranium enrichment process, and although it is continuing to increase overall enrichment output, the number of working centrifuges at its disposal is decreasing.

However, it also notes the recent provocative Iranian decision to enrich uranium to 20% the uncovering of a previously secret enrichment plant in Qom and the current Iranian attempts at converting enriched uranium hexafluoride gas into uranium metal.

It is clear the Iranian regime led by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has strongly wedded itself to a nuclear policy. As top analyst Reuel Marc Gerecht notes elsewhere in this edition:

It really ought to be obvious by now that unless Khamenei is on his knees, he’s not going to stop uranium enrichment. His commitment to developing nukes is probably as strong as was Khomeini’s determination to destroy Saddam Hussein in the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war. The shock that stopped Khomeini – the realisation that the conflict was threatening his regime’s survival – ought to tell us what kind of shock we need now.

The pro-democracy ‘Green movement’ in Iran has been rattling the confidence of the ruling elite since last June’s rigged election, and is the only thing likely to provide the needed “shock” to the regime.

The new IAEA report means that Russia and China, which have been resisting a new round of UN sanctions against Iran, have lost one excuse for continuing to be obstructionist.

It is reported that when Israeli PM Binyamin Netanyahu visited Moscow in mid-February, he found Russia no longer repeated previous denials of evidence that Iran is seeking nuclear weapons.

And indeed, since September last year, when the Qom enrichment facility was uncovered, Russia has been increasingly vocal in its criticism of Iran, leading some to predict that Moscow might be coming round to agreeing to reasonably tough sanctions against Teheran.

Netanyahu also hopefully convinced Russia to continue delaying the delivery of the highly advanced S-300 ground-to-air missiles, which it sold Iran in 2005. If this system is supplied, the risk of an early Israeli military strike on Iran will increase dramatically, as Jerusalem witnesses the closing of a window of opportunity to prevent a nuclear-armed Iran before the S-300 system makes Iran’s nuclear sites much less vulnerable to conventional attack.

Meanwhile, Israel’s Deputy Prime Minister Moshe Ya’alon was off to China for trade talks that are sure to include a substantial component related to the Iranian crisis.

However, even in the event that China gives up its current opposition to any new sanctions on Iran, the likelihood is that the best that can be agreed upon at the UN are fairly limited sanctions, targeting a few Iranian banks, businesses and individuals, primarily associated with the ruling Revolutionary Guards.

While there may be merit in such sanctions as part of a larger package, they are almost certainly not going to work in and of themselves.

Meanwhile, Iran imports nearly 40% of its refined petroleum needs, most of this from Western sources. If this was blocked through direct sanctions against oil companies or through sanction pressure on insurance companies, this would have a major impact on the degree of popular unrest, as riots which followed petrol rationing in 2007 demonstrated.

The regime would, of course, blame the resultant hardships on America. But every failure of the Islamic Republic for the last 31 years has been blamed on America, which explains some of the popularity the latter has in the hearts of millions of Iranians.

Both houses of the US Congress have passed bills allowing the US to impose such sanctions unilaterally.

The US Administration should now be building a coalition of partners willing to support such sanctions – including Australia – without necessarily abandoning the UN track and achieving whatever pressure can be added from that outlet.

There is no point in again recounting how dangerous and destablising a nuclear Iran would be, nor how limited the time is to stop it. Short of a military strike, with all its dangers and costs, only a threat to the regime’s survival appears credible as a means to do so. Any campaign of sanctions must now be targeted to force Iran’s leaders to confront this stark choice – give up their illegal nuclear quest or risk the very existence of the Islamic revolution.

Tags: International Security