Australia/Israel Review

Editorial: The Iranian charm offensive

Oct 29, 2013 | Colin Rubenstein

Colin Rubenstein

There is a definite international diplomatic buzz over new proposals floated at October’s P5+1 talks in Geneva aimed at curbing Iran’s nuclear program. The Islamic Republic’s PR makeover, which began with the election of Hassan Rouhani in June and continued with a charm offensive at the UN General Assembly in September, appears to now be complete.

Whether the transformation is merely cosmetic – as Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu has emphatically and correctly warned it likely is – or heralds the improbable beginning of a major, genuine policy shift from a sanctions-weary regime is of course not yet entirely conclusive.

One thing, however, is for certain. The reported proposals that Iran brought to the table in the most recent talks appear to be categorically unacceptable because, as Yediot Ahronot‘s defence analyst Ron Ben-Yishai has correctly noted in this edition, they would leave Iran with almost all of its nuclear weapons program infrastructure intact while also bestowing international legitimacy on future Iranian nuclear development.

The proposal seems tailor-made to allow Iran to strategically pause the advancement of their program – perhaps even fully cooperating initially with weapons inspectors – but with the ability at any time to expel the inspectors, reactivate high-level enrichment and build a nuclear device in a matter of weeks. By timing any such move carefully, Iran would stand an excellent chance of crossing the threshold to nuclear weapons capability before the international community would have time to react.

In other words, Iran could essentially have military nuclear capability – the ability to swiftly deploy nuclear weapons if needed – while maintaining the illusion of complying with international obligations and ending the sanctions that are clearly seriously damaging the Iranian economy.

Indeed, Iran’s proposal may be simply an attempt to replicate the North Korean playbook, whereby Pyongyang successfully zig-zagged its way to a nuclear weapon in 2006 through a series of agreements in which they ostensibly pledged to dismantle their nuclear program.

Yet as worrisome as a nuclear armed North Korea has been for the Asia-Pacific region, the dangers posed by a nuclear armed Iran would be immeasurably worse. As Prof. Efraim Inbar noted during his AIJAC-sponsored visit in October, the reasons for this are threefold.

Firstly, a nuclear Iran would spark nuclear proliferation throughout the Middle East, as Sunni powers such as Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Egypt scramble to offset Iran’s advantage. Secondly, Iran because of its location, has the potential and the ambition to control both the Persian Gulf and Caspian Basin oil regions which hold most of the world’s reserves. These designs may include placing Shi’ite-majority areas within the Gulf states under an Iranian protectorate. Finally, a nuclear Iran would embolden the regime’s already uniquely extensive infrastructure and sponsorship of global terrorism directly and via proxies, while simultaneously making them nearly impossible to deter.

For those reasons and more – including the hardening of a nuclear-armed regime’s hold on power – it is imperative that Iran be prevented from reaching nuclear weapons capability or even approaching it, given the fallible nature of intelligence on what is occurring within Iran.

Since the election of Rouhani, Western countries led by the United States have renewed their investment in diplomacy as the tool for attaining this goal, but have wisely kept their sanctions regime against Iran fully intact, and reinforced their avowal to leave all options on the table – including the military option – should diplomacy fail.

Hopefully, as Prime Minister Netanyahu told US Secretary of State Kerry in Rome on Oct. 23, they will never lose sight of the fact that striking a bad deal with Iran would be worse than making no deal at all.

What is a bad deal? It is any agreement that does not substantially turn back the clock on Iran’s timeline towards nuclear weapons capability.

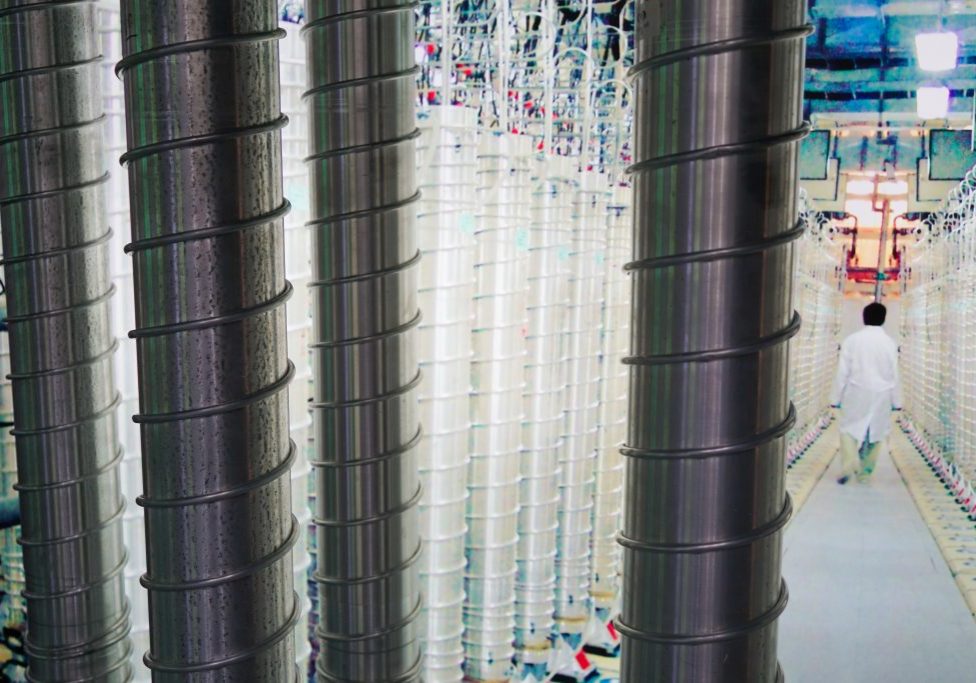

A good deal would mean removing the majority of Iran’s large enriched uranium stockpile, dismantling at least most of the vast enrichment capacity they have developed to swiftly convert that stockpile into bomb fuel, and ending plans to start up the plutonium-producing Arak heavy water reactor. It would mean unrestricted access by nuclear inspectors to any Iranian facility, at any time, to verify compliance and potent and immediate consequences for non-compliance.

Western negotiators are now faced with the challenge of selecting bargaining chips to be used to gauge Iran’s sincerity, without weakening sanctions that may be almost impossible to reimpose.

Offering a one-off incentive, such as unfreezing some of Iran’s overseas funds, could be one appropriate tactic. While the amount of currency at stake is substantial and would provide short-term relief to Iran, it is finite and would thus maintain the West’s long-term leverage on Teheran.

On the other hand, the P5+1 must demand from Iran – as a veteran flouter of clear legal obligations with a long history of deliberating using negotiations merely to buy time – only concessions of lasting value.

An extended process of “confidence-building” whereby sanctions are gradually lifted in exchange for small and easily reversed concessions from Iran – such as suspension of the enrichment of uranium to medium levels – is a recipe for failure. Firstly, because there is no time for any such drawn-out process given how close Iran is to a situation where it can likely break-out and produce nuclear weapons before they can be detected. And secondly, because almost all experts agree that if the sanctions are fully or partially lifted, it will be extremely difficult and time-consuming to gain the international consensus needed to re-impose them if Iran reverses course.

At the eleventh hour, as Iran stands poised on the cusp of nuclear weapons capability, any margin for error by negotiators is razor thin. They must err on the side of caution, with terms on offer that emphasise protecting the global community over appeasing Iran’s bruised ego.

Tags: International Security