Australia/Israel Review

Editorial: Back from the Brink?

Nov 21, 2013 | Colin Rubenstein

Colin Rubenstein

The recent disagreement between Israel and the United States over the parameters of an interim Iranian nuclear deal is significant, but its importance should also not be exaggerated.

The Israeli position on the diplomatic next step – as outlined by Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu – and the attitude of the P5+1 – greatly influenced by US President Barack Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry – have been at odds with one another. However, this is a disagreement on tactics, not goals.

The strategic objective remains the same – preventing Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons or the capacity to build them quickly when required. In geopolitical terms, the latter would not be much different from the former.

The tactical differences on how to achieve this shared end are not a product of personal friction between the US and Israeli leaders. Rather, they reflect the different timetables that Washington and Jerusalem confront when gauging the time left for diplomacy, and their differing views over what constitutes a good deal in the short term as a way to facilitate the shared longer term goal.

The White House, which due to its vast military strength has more time to explore diplomatic options, is making it clear to Congress that it is not currently interested in imposing stronger sanctions on Iran, preferring instead to explore whether the conciliatory tone coming from Iran’s new President Hassan Rouhani might create positive diplomatic opportunities.

The US-led P5+1 has been therefore been looking to buy time to evaluate Iran’s sincerity through a deal that freezes Iran’s illegal nuclear program in return for a partial lifting of sanctions or other financial incentives.

Yet the Israeli political and security establishment believe, almost unanimously, that the Western powers risk making a grave mistake. Interestingly, Israeli alarm is shared by many of its traditional adversaries in the Arab world, especially in the Persian Gulf.

In their shared assessment, an interim deal of the kind being brokered is dangerous on several levels.

First, it breaks the momentum of economic pressure through sanctions that brought Iran to the negotiating table in the first place – momentum which may prove difficult to restore.

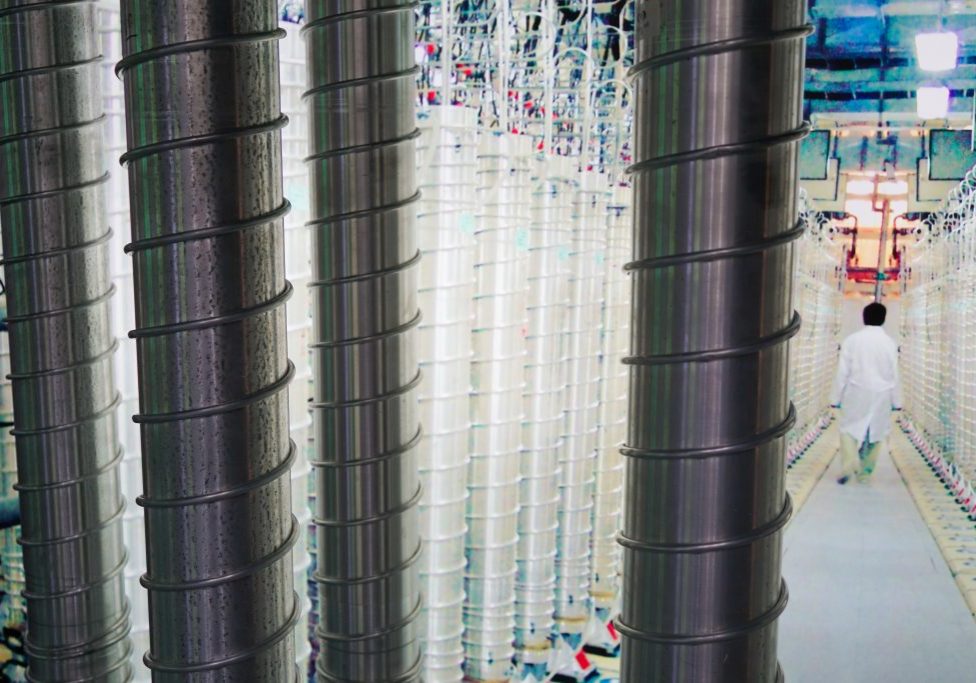

Secondly, such a freeze would leave Iran with sufficient nuclear building blocks to make a dash for nuclear weaponisation whenever desired. Iran already has sufficient low enriched uranium to make at least six bombs, and has built enough centrifuges, including some new highly efficient models, to rapidly enrich this uranium to military grade. The highly-regarded experts at Washington’s Institute for Science and International Security estimate that its current infrastructure will allow Iran to create a bomb core out of its low-enriched stockpile in under a month.

Further, given the current advanced stage of Iran’s nuclear development, the six months of “freeze” that the West has been seeking might potentially be enough time for Iran to reach what former Israeli Defence Minister Ehud Barak described as the “point of invulnerability”.

Iran can “freeze” its current nuclear progress and still use the next six months to disperse or place new protections around the existing infrastructure – to the point where the Israeli military might have little chance of successfully conducting a military operation that would significantly damage that nuclear infrastructure.

This is one of the key reasons behind Prime Minister Netanyahu’s recent warning that a “bad deal” could lead to the “undesired option” of war. Israel has been consistent in its message that it will not allow itself to be put in a position where it would have to rely on other countries to prevent Iran from building a bomb.

Thirdly, there is the concern that an interim deal would fail to lead to a comprehensive agreement, but the diplomatic process would nonetheless be reshaped by the precedent of signing a deal which would essentially license Iran to continue to violate binding UN Security Council resolutions forbidding it from enriching uranium. At the end of any interim deal, Iran would retain its current advanced state of nuclear development but with the blessing of prior signed agreements which Teheran could argue legitimises the continued possession of such materials and infrastructure indefinitely.

For these reasons and more, Israel sees any interim deal that does not substantively roll back the amount of time it would take for Iran to achieve a nuclear “breakout” as both dangerous and damaging to the prospects for diplomacy to succeed.

The US fully understands Israel’s arguments over how to handle negotiations with Iran, but disagrees with them, arguing compliance with sanctions could erode if too hard a line is taken. Where does that leave the relationship between Washington and Jerusalem?

In many ways, it leaves it virtually unchanged. Disagreements, even about vitally important issues like Iran’s quest for nuclear weapons, are to some degree par for the course for allies like the US and Israel which have very different geopolitical interests and roles. Nor is a public airing of them new.

Indeed, most observers of the Iranian nuclear crisis today admit that Israel’s “bad cop” role in pushing for tougher action has substantially contributed toward both bringing about stringent global sanctions and forcing a re-think on Teheran.

This edition is going to print just before the crucial round of the Geneva negotiations between the P5+1 and Iran set to begin on Nov. 20. If the leaders of the P5+1, and especially Washington, are wise they will heed the warning of those who actually have to live in the same region as Iran. The world is already too close to the brink of the disaster that a nuclear-armed Iran would be. Both in the short and long term, the only diplomatic agreement with Iran worth having is one that involves a concrete, unequivocal step back from that brink – meaning the assets that Iran will use to make a nuclear bomb must not be just frozen, but significantly reduced.

Tags: International Security