Australia/Israel Review

Cine File: Not quite Heaven

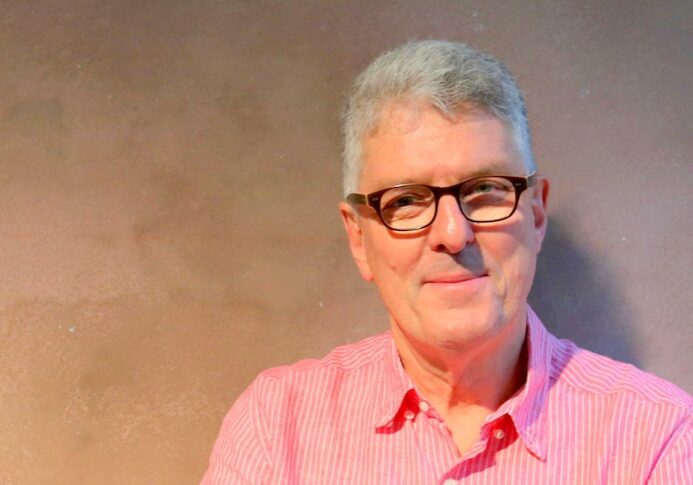

Jul 28, 2020 | Allon Lee

It Must Be Heaven

It Must Be Heaven

Director/Writer: Elia Suleiman

Writer/director/actor Elia Suleiman, who was born in Nazareth in 1960 and is of Greek Orthodox background, is one of the seven percent of the Arab citizens of Israel who identifies solely as Palestinian, and not some variation of Arab or Palestinian-Israeli.

The distinction is relevant when trying to analyse and understand Suleiman’s fourth feature film, It Must Be Heaven, in which he plays a fictionalised version of himself called “ES” who travels from Nazareth to Paris and New York and then back home.

The arthouse movie garnered largely positive reviews upon its recent Australian release. Most reviewers have focused on the film’s undeniable charm. Whimsical and droll, the highly visual world that Suleiman has created and populated with eccentric characters and absurdist set-pieces offers a wry and smartly packaged commentary on the quirks of contemporary societies.

But the film can also be read as a commentary on identity and place – what it means to be Palestinian, how others see Palestinians and what might the fate of “Palestine” be – something which has attracted less analysis.

Suleiman doesn’t provide clear cut answers and many scenes dealing with “Palestine” are dreamlike, oblique and fantastical.

Israel’s presence in the film is muted and absent, with Suleiman wiping it off the map metaphorically and literally too.

Early on, viewers see street art in Nazareth showing a map of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza coloured as a Palestinian flag with the symbolic key of return alongside it.

More than once, Nazareth – a town which has been part of northern Israel since 1948 – is described as being in Palestine.

Visiting New York, a taxi driver asks him, “What country do you come from?” and viewers hear the only four words ES speaks in the whole movie, which are, “Nazareth. Nazareth”. The driver responds, “Nazareth, is that a country?”. To which ES adds, “I’m Palestinian.”

This deliberate ambiguity again crops up in the only scene where the name “Israel” is explicitly mentioned in the movie.

Real-life actor Gael Garcia Bernal – who plays himself – tells someone on the phone, “I’m here with my friend Elia, Elia Suleiman. He’s a Palestinian from…No, he’s not a Palestinian from Israel. He’s a Palestinian from Palestine. Yes, a Palestinian from Palestine. Yes, Palestine.”

Meanwhile, a comical scene set in Central Park shows a woman who is wearing a pair of wings remove her top to reveal a Palestinian flag painted across her bare chest with the words “Free Palestine”, before leading a group of New York’s finest on a merry dance as they try to cover her up.

When they eventually do, she literally disappears, leaving only the wings behind.

Later on, during what appears to be a Halloween street party, we see her or someone similar, minus Palestinian symbols, riding a bike, watched by a Grim Reaper figure, who then exchanges glances with ES.

Whilst in New York, a fortune teller tells ES, “there will be Palestine. Absolutely. It’s gonna happen… But… It ain’t gonna happen in your lifetime, or mine.”

These themes of rebirth – including the references to “Palestine” – are scattered across the length and breadth of the film.

Symbolically the movie begins at night during Easter in Nazareth as a Greek Orthodox priest leads his congregation in a street procession and recites prayers whose lines state that “Christ has risen from the dead” and is “bestowing life” on the dead. It should be noted that Suleiman has said this scene is not connected to the rest of the movie.

This beginning is bookended by a final scene set in a darkened nightclub filled with carefree young people dancing to a traditional-sounding song titled “I am an Arab” that has been given a techno arrangement. Then, as it fades to black, the words “To Palestine” appear onscreen.

Another allegory for Palestine is a mysterious woman in an olive grove wearing a traditional Arab dress called a thobe. ES watches her labour to transport two pots of water.

When ES returns to the grove after his trip abroad, one of the water cisterns she carries is empty and she removes her headscarf to literally let her hair down.

Given this precedes the nightclub scene, it appears to signal an attempt to reframe Western expectations of a Palestinian.

The few times Israelis appear in the film, they do so in a security capacity and have difficulty seeing what is in front of them.

In Nazareth, Israeli police steal binoculars from a passing street vendor to monitor a man who stands only metres away urinating in the street and then, possibly, arrest him off-camera.

When ES is driving, a car with two soldiers who are recklessly exchanging sunglasses overtakes him. In the backseat is a doppelganger for the Palestinian teen activist Ahed Tamimi, whose trial and conviction for slapping a soldier in 2018 became a cause célèbre for Palestinian activists. The Tamimi look-alike is blindfolded but turns her face to look at ES and the audience.

This general tone towards Israelis conforms with comments Suleiman made in a 2010 interview on Electronic Intifada, in which he said that “really they are so obnoxious, the Israelis – the Israeli institution and the government.”

Of course, this is not a movie, per se, about Israel, but about Palestinians and Suleiman wants to send the message that Palestinians are being objectified as a hot button social issue and not necessarily treated as flesh and blood people.

The aforementioned taxi driver treats ES as a novelty when he learns he is Palestinian. He tells him “Goodness gracious! Let me look at you, I’ve never seen a Palestinian!” and phones his wife to share this rare sighting.

Likewise, whilst in New York, ES participates in the 10th Annual Arab American Forum for Palestine and sits on a crowded dais of po-faced experts. The audience are all starry-eyed, enthusiastic, “yes” men and women.

In Paris, a movie producer’s sympathy with the Palestinian cause extends only so far, as he rejects “ES’s” request for funding, telling him the script is not “Palestinian enough… We were under the impression that it would take place in Palestine…but it might as well be anywhere. It could even take place here.”

Pro-Israel viewers frustrated by the mass media’s propensity to depict Palestinians purely as noble victims will appreciate some of these moments. Even if Suleiman’s rationale for including them is entirely different, they do speak to a larger truth and add nuance to the movie.

Whilst the film does include subtle jabs at his fellow residents of Nazareth, Suleiman’s satirical lens is never turned against the Palestinian national movement, preferring instead the all too familiar paradigm of mocking the West and Israel for their obsession with security.

The sections in France and New York include comical scenes of elaborate interplay between overly officious security personnel and citizens who themselves are heavily and comically armed.

As Suleiman explained in a quote that appeared in the Australian, “If my previous films tried to present Palestine as a microcosm of the world, my new film… tries to show the world as if it were a microcosm of Palestine.”

In this there is a faint echo of the old Palestinian political line that there will be no peace anywhere until the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is solved.

In the 2010 interview, Suleiman certainly suggested he believes this, saying, “The Arab-Israeli conflict is the world’s conflict and vice-versa, so I don’t know what is a microcosm of what anymore, because globally, Palestine has multiplied and generated into so many Palestines. Because I feel if you go to Peru, you will find Palestine in a grave state there too… My films do not talk about Palestine necessarily. They are Palestine because I am from that place – I reflect my experience, but in identification with all the Palestines that exist. The word ‘Arab-Israeli conflict’ is alien to me in terms of the poetics of the word.”

In the same interview Suleiman said Israel had stolen falafel and hummus as national symbols – a common Palestinian nationalist claim – and added: “they’re absolutely pathetic.”

It is not necessary to be aware of any of these textual and political threads to see this movie, of course, but it can assist in a greater understanding of what is going on below the surface.

Yet, despite these undercurrents, it is still entirely possible to enjoy this film whilst disagreeing with many of Suleiman’s contentious but subtle political points.

Tags: Media/ Academia, Palestinians