Australia/Israel Review, Featured

Bound for Unity?

Sep 26, 2019 | Ahron Shapiro

Lessons from Israel’s past

The outcome of the September 17 election for Israel’s 22nd Knesset has left both of the two largest parties and their respective blocs far short of being able to reach the 61 seats necessary to form a majority government.

As noted elsewhere in this issue, while there remain some possible scenarios where the hung parliament could lead to various different coalitions, most analysts agree the most likely outcome from the deadlock is some form of a unity government.

Unity governments have been formed seven times in Israel’s 71-year history. The first was formed in 1967 in the tense leadup to the Six Day War; the second and third in 1969 and 1970. The sixth was in 2001, and the seventh and most recent was in 2012 – but all but two were unity governments of choice assembled at times of national need. All but one were led by a single prime minister.

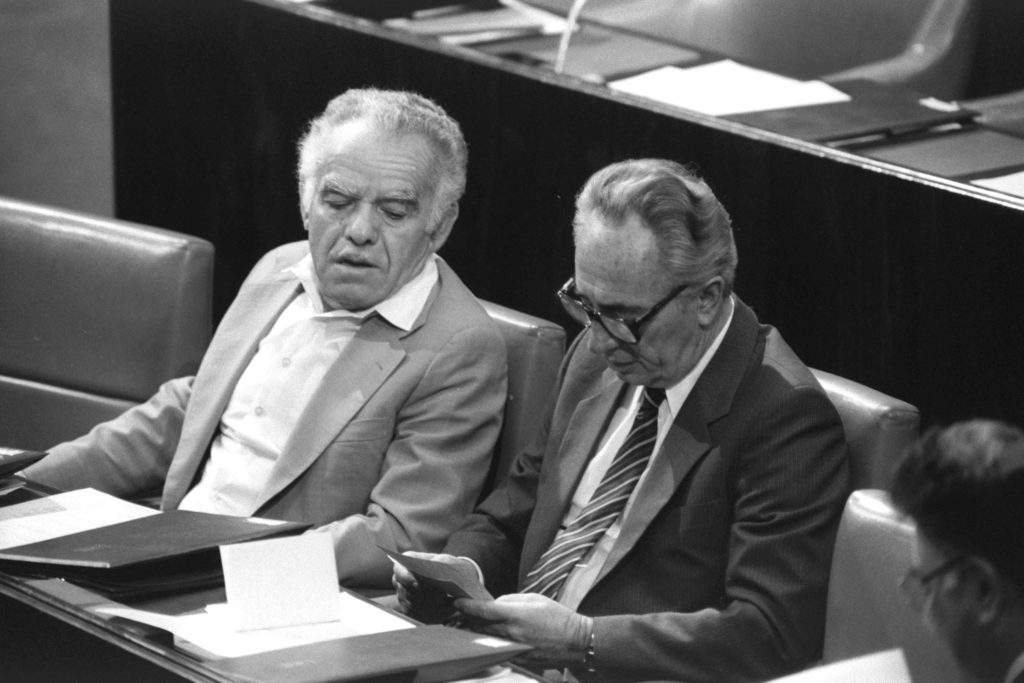

The exceptions – those that were formed due to the lack of any other option – were the fourth (1984-1988) and fifth (1988-1990), each involving Labor (led by Shimon Peres) and Likud (led by Yitzhak Shamir) as the senior partners. In these two Knessets – the 11th and 12th – the results left the parties in a post-election “Mexican Standoff” situation not unlike the one they find themselves in today.

The first government involved a deal to rotate the prime ministership between party leaders. In 1984, Peres led first as PM with Shamir as his Foreign Minister, then vice versa.

In 1988, Shamir was in a slightly stronger political position and did not agree to rotate leadership, while Peres continued as Foreign Minister. Halfway into the fifth unity government’s term, Peres believed Labor had found a path to a Labor-led coalition and successfully brought down the government with a no-confidence motion in what came to be known as the “stinking manoeuvre”. However, after a short period of chaos, it was Shamir and not Peres who succeeded in cobbling together a conventional narrow coalition with several smaller parties.

Of the two unity governments of the 1980s, the first was therefore most evenly divided, something which required unique mechanisms to implement. To cope with the lack of trust inherent to such power-sharing arrangements, an unprecedented ten-seat inner cabinet divided equally between Labor and Likud was set up to ensure that each party could block, if necessary, the initiative of the other.

In his speech to the Knesset announcing the fourth unity government on Sept. 13, 1984, Shimon Peres said, “This is a government born on riven land, formed not based on any precedent and completed by delicate work of overcoming difficulties.

“The government embarks on its way with the nation’s hope that people with opposing views will grow closer, and that common elements will be used to better serve the people in handling urgent challenges in multiple and diverse areas.

“This is a government that will have to rely on good will no less than the power of the majority. This is a government that will have to prove that governance means persuasion. The mere fact that the two big political camps in Israel decided to combine forces to drive the nation forward has created hope in Israel, and esteem outside of it.”

Looking back on the unity government of 1984, a unity government between Blue and White and Likud today, while likely a rancorous and noisy affair, could nonetheless be in a position to produce achievements that might elude a narrower coalition led by either party on its own (were this even possible).

In the summer of 1987, towards the end of the first Peres-Shamir unity government, American political scientist Scott D. Johnston took stock of how that government had fared in a paper for the Purdue University’s Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, Shofar. Johnston painted a picture of a government at odds with itself that paradoxically was nonetheless seen as a success in terms of furthering the national interest.

To be sure, the Peres-Shamir unity government of the thirteenth Knesset was exceptional for the amount of infighting and internal rancour it exhibited. As Johnston put it: “The amount of distrust, bickering, bad manners, and outright internecine warfare within the unity government was on a sustained basis above and beyond anything experienced in any other period of Israeli statehood.”

Johnston described a government seemingly teetering from one coalition crisis to another, with all the decorum of a barfight.

“An examination of the national unity government reveals a repeated pattern of coalition rifts threatening to bring down the government, and then reconciliations,” he wrote. “A succession of episodes and crises, name-calling and backbiting chronically surfaced on a more or less sustained basis and on a level not encountered in previous Israeli governments. Press accounts referred repeatedly to ‘scathing denunciations,’ ministers calling one another ‘liar,’ and the like. Likud was accused of ‘running amok’ by [Labor] Health Minister Mordecai Gur; Shamir accused Peres of attacking Likud nearly every day; Labor Party Secretary Uzi Baram characterized [the Likud’s] Ariel Sharon as sticking a knife in the nation’s back; Sharon referred to the outright hatred Labor cabinet ministers felt for Jewish West Bank settlements; [former Labor Foreign Minister] Abba Eban termed Sharon ‘a driver with seven accidents who wants to be a driving teacher,’ to which Sharon responded that ‘Eban never fought for Israel, but always sought to make personal profits from our tragedies.’”

And yet in spite of this atmosphere, the unity government of 1984-1988 was capable of creating major cooperative achievements for the country, such as ending Israel’s runaway hyperinflation of the period (which had reached as high as 500%) and bringing to a close the First Lebanon war.

“Some rather clear-cut credit may be assigned to the unity government,” Johnston noted. “The most important one was dealing with the perilous state of the economy. Managing the economy and getting inflation under control required a level of inter-party cooperation in imposing quite painful policies vis-a-vis wages, economic controls, and cutting price subsidies. Despite a great deal of tugging and hauling on these policies, cooperation held to the extent that the policies worked. It is difficult to see how such harsh economic medicine could have been successfully administered by a coalition government led by only Labor or Likud without the party on the outside of the coalition trying to obstruct or take partisan advantage.”

From the perspective of today, it can be argued that the success of the fourth unity government in stabilising and reforming Israel’s finances paved the way for the explosive success of “start-up Israel” in later decades.

Further, Johnston wrote, “the withdrawal from Lebanon which was completed in all but minor respects by June of 1985 can properly be recorded as a major achievement of the unity government… [it] was not something that was to be taken for granted. It was done within the framework of that unity government, and Likud as a major partner accepted it.”

The experience of the 1984 and 1988 unity governments provides insight into what such an arrangement might produce for Israel today, as well as lessons of what pitfalls can be avoided as follows:

• The prime ministerial rotation between Shamir and Peres proved that such unconventional arrangements between rival parties can actually be as stable, or even more stable, than conventional governments.

• Popular perception that unity agreements favour the leader who goes first as PM has no historical basis: Shamir was second in the 1984 rotation agreement, but it could be argued that precisely because he went into the 1988 election already as prime minister, this gave him the opportunity to campaign with the advantage of being the incumbent. Meanwhile, Peres’ famous “stinking manoeuvre” of 1990 shows that there is often a political price to be paid for abrogating unity agreements prematurely when it seems convenient to do so.

• While governments that combine ministers from ideologically opposed parties can be full of acrimony, the rivalry that creates such friction can also fuel competition within the coalition to outdo one another in terms of delivering quality government in each portfolio so as to position their party best for the next election.

• Unity governments can be excellent vehicles for achieving a national agenda based on broad consensus; especially taming budgets by lessening the power of niche parties to leverage their demands on state coffers; and dealing with major security challenges – such as those Israel currently faces in Gaza and in terms of the Iranian military build-up in Syria and its precision missile project in Lebanon.

Tags: Israel