Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: Hezbollah’s global reach

Jan 29, 2014 | Paul Monk

Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God

Matthew Levitt, Hurst and Co., London, 2013, 426 pp., $49.95.

Paul Monk

Matthew Levitt has now given us three landmark books on radical Islamic terrorism, Hamas: Politics, Charity and Terrorism in the Service of Jihad (Yale University Press, 2006), Negotiating Under Fire: Preserving Peace Talks in the Face of Terror Attacks (Rowman and Littlefield, 2008), and Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God (Hurst and Co., London, 2013). The first and third of these are very useful, meticulously researched and documented accounts of what makes both Hamas and Hezbollah terrorist organisations and not simply political movements with a military “wing”. The second is a valuable, case-study based reflection on how to resist the psychological and political pressures that terrorism can exert in a bid to upend constructive negotiations.

Levitt has an interesting background. He has worked for the FBI and the US Treasury Department on counter-terrorism and intelligence. He has been an adviser on terrorism and counter-terrorism to the US State Department, has taught at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, held fellowships at the US Military Academy and the Homeland Security Policy Institute at George Washington University, and is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. He is currently Director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s Stein Program on Counter-terrorism and Intelligence. He has been in Australia recently, giving talks and interviews about his latest book.

Should you take the time to read it?

Yes, if you want to understand three things: (1) that Hezbollah is a terrorist organisation and not merely or simply a Lebanese activist or “militant” political organisation; (2) that Hezbollah operates not only in Lebanon, or the wider Middle East but globally, as a radical jihadist and criminal organisation; and (3) that the surveillance and security measures required to monitor its global operations and keep it in check include much of the phone, email and financial transactions monitoring and many of the covert operations measures that the leaks by individuals such as Bradley Manning and Edward Snowden have exposed and which have been the subject of considerable, often heated, controversy in recent years.

There are two other aspects of the matter, however, that throw into high relief why all the above considerations are important. The first is that the phenomenon of terrorism in a globalised world continues to be poorly understood, which gravely hampers efforts to reach both practical and legal consensus on measures to contain and uproot it. The second is that Hezbollah has been, virtually from its inception, a client of the radical Shi’ite regime in Iran and its global reach, its hostility to the State of Israel and also its current virulent role in the civil war in Syria must be seen in this context. Too often, neither of these things is understood. This was breathtakingly evident in 2006, when the British Left proclaimed “We are all Hezbollah now!”

My own thinking about terrorism and the challenges of 21st century asymmetric warfare has been decisively shaped over the past decade by the work of Philip Bobbitt. His two major treatises, The Shield of Achilles (Knopf, 2002) and Terror and Consent (2008) provide a deep historical and philosophical framework which enable us to put detailed case histories or research projects such as those of Matthew Levitt into a deeper context.

In chapter 15 of The Shield of Achilles, Bobbitt analyses the 1964 Kitty Genovese case, in which dozens of neighbours stood by and did nothing while a young woman was stabbed to death. The poignant incident has become a paradigm case for thinking about crime/terror/aggression and the psychological reactions of onlookers. Thinking through the case can enable us, as he shows, to understand why the international response to terrorism is so often confused, disjointed, reactive, paralytic or controversial.

Bobbitt concluded that there are five successive stages through which a bystander (whether an individual in New York in 1964, or a state in the early 21st century) must successively pass before there can be an effective response to a violent act: the bystander must (1) notice that something is happening at all; (2) recognise it as untoward or objectionable; (3) decide that something must be done; (4) assign responsibility for someone to do that something; and (5) implement or see to the implementation of such action. “If at any stage in this sequence,” he commented, “a crucial ambiguity is introduced, then the whole process must begin again.” Thus, he remarked, despite horrifying events over three years (1991-94) in the former Yugoslavia, the “international community” was unable agree on any coherent response to the violence in Bosnia.

In Terror and Consent, Bobbitt argued at great length that the kind of terrorism we are now seeing remains badly understood, with the consequence that our responses to it have been confused, hesitant and controversial.

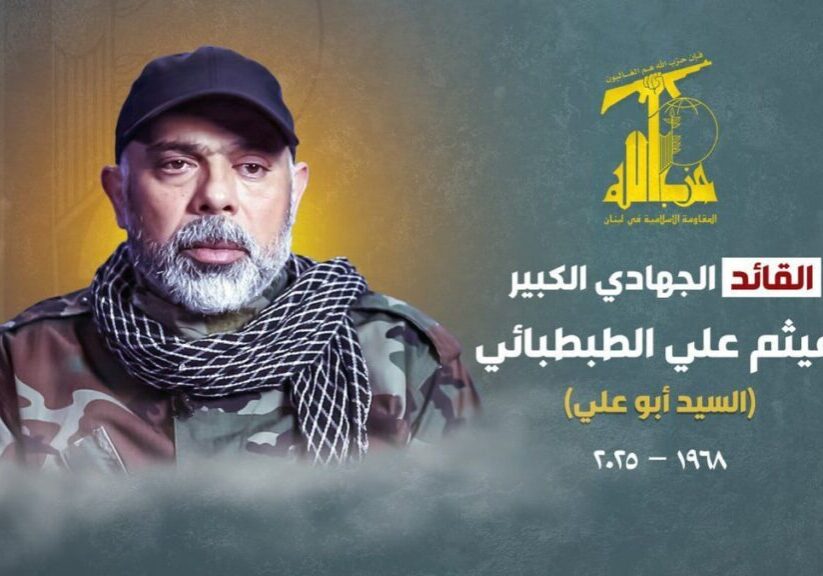

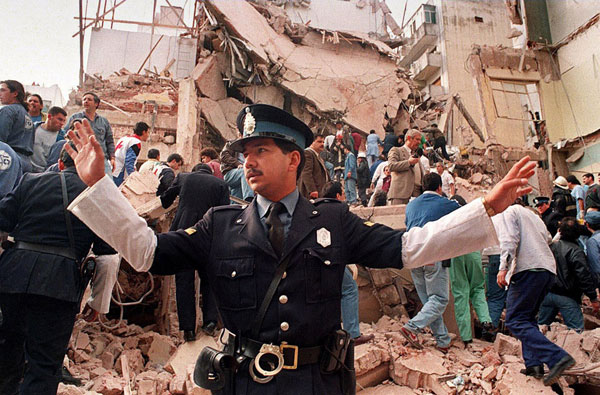

When I read Matthew Levitt, I read him through these lenses. I read of Hezbollah’s deadly grip on Lebanon and its lethal struggle against Israel, or its close alignment with the regime in Teheran; but I note especially the “global footprint” of Hezbollah and I think in terms of Kitty Genovese and of the “novelty of the problem we face.” Levitt shows Hezbollah plotting and carrying out what can only be described as terrorist violence right around the globe. Among cases that take us to both North and South America, into Asia and Africa and across the Middle East, perhaps none is more significant than his account of the bombings in Buenos Aires in March 1992 and July 1994. The first was an attack on the Israeli Embassy, the second the bombing of the AMIA (Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina) building, in which 85 people were killed and 150 injured.

Certainly, both targets were Jewish and the first an outpost of the Israeli state, but the willingness and capacity of Hezbollah to conduct such operations half a world away from its Lebanese bases, the fact that the Iranian regime was demonstrably involved in the operational planning and the fact that Israeli, American and Argentine police and intelligence agencies were all involved in investigating the attacks and tracing the guilty parties through phone intercepts, emails, passports and so forth; all make this part of Levitt’s book a bracing case study in the nature of the problem and the tools of counter-terrorism. It also makes clear that we should use the word “terrorist” and not “militant” to describe those who conduct such attacks, since they do not meet any of the criteria of conventional or legitimate acts of war.

This last point is of particular importance when we weigh up the strategic alliance between Hezbollah and its paymasters in Iran. In his concluding chapter, “Shadow War”, Levitt writes of the Israeli effort, through targeted assassinations and sabotage, to retard Iran’s nuclear weapons program. He contrasts this with Iranian and Hezbollah retaliation against soft Israeli or even international Jewish targets. Are both sets of actions “terrorist”? They are not. We need to be clear in our minds about this distinction, since otherwise we will become like the bystanders who observed Kitty Genovese being stabbed while paralysed into inaction somewhere along the five point decision spectrum specified by Philip Bobbitt.

The Israeli acts are covert operations directed very specifically at key figures involved quite knowingly and at a high level in developing a strategic capability that would pose an existential threat to Israel. The Iranian and Hezbollah acts are brutal acts of violence intended to have a psychological shock effect, directed at innocent third parties, such as the families of Israeli diplomats or Israeli tourists in third countries. Levitt illustrates this by citing the assassination of Mostafa Ahmadi Roshan, the deputy director of the Natanz uranium enrichment facility and the retaliation directed at the wife of the Israeli defence attaché in New Delhi. The first was a tough-minded “James Bond” style operation in a shadow war; the second was an act of terror, pure and simple.

One is left with the impression, by the close of Levitt’s book, that the counter-terrorism struggle against Hezbollah is being won. He writes, “All told, more than twenty terror attacks by Hezbollah or Qods Force operatives were thwarted over the fifteen month period between May 2011 and July 2012; by another count, nine plots were uncovered over the first nine months of 2012.” But the evidence in the book should lead us to two conclusions: that it has taken a concerted, large-scale and largely undercover international effort to thwart all these attacks and that Hezbollah remains as committed as ever to its violent jihadist agenda.

This should lead to a clear headed assessment of the need for an international counter-terrorism regime able to thwart such organisations and operations. It should also prompt a wider international discussion of this problem. That, Matthew Levitt concludes, is exactly what he hopes his book will trigger. He should be warmly thanked for his contribution.

Paul Monk is Managing Director of Austhink Consulting and holds a PhD in international relations from the Australian National University. He is a widely published commentator on public affairs and is the author of four books, including most recently, The West in a Nutshell: Foundations, Fragilities, Futures (Barrallier Books, 2009).