Australia/Israel Review

Afghanistan on the brink?

Jul 4, 2017 | Michael Rubin

Michael Rubin

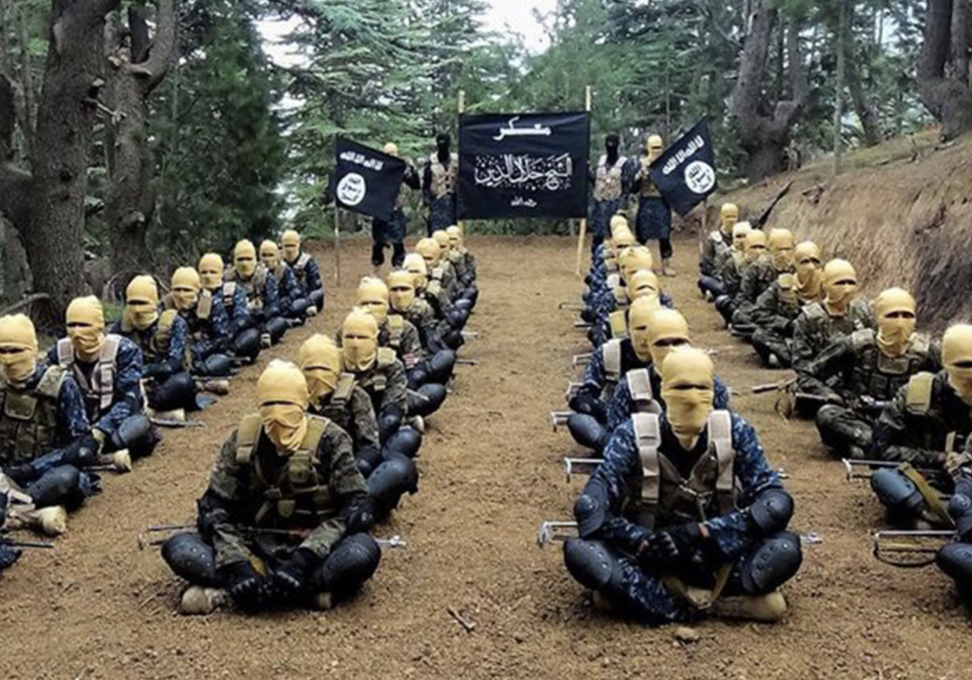

On June 13, US Defence Secretary Jim Mattis told Congress that the United States was “not winning” in Afghanistan. That is the understatement of the year. While President Trump has authorised Mattis to call up some additional troops, there remains no comprehensive strategy for victory, let alone stability, and the numbers of troops available seems the equivalent of addressing a sucking chest wound with a band-aid. Both the Taliban and the Islamic State are resurgent in vast sections of the country. Many NATO partners are quietly giving up and the mood in Congress ranges from impatient to defeatist.

It didn’t have to be this way.

While intervention was necessary to oust the Taliban, when the history of American involvement in Afghanistan is written, there will be many problems to address:

Short-sighted political strategies: Afghanistan did not have the logistical capability for the United States to flood troops into the country because neither the Taliban nor the Mujahedin nor even the Soviets had built the airfields and infrastructure to adequately support large deployments outside the major cities; Afghanistan was not like Iraq in which Saddam Hussein’s regime had built numerous airfields out in the desert and in sparsely-populated regions. Because Afghanistan had been without a government for so long, had no military to speak of, and was dominated by warlords, the US strategy was to build a new army from the bottom up while co-opting warlords with plum positions. That gave the Afghan army time to strengthen since, initially, it would never be able to defeat the warlords simultaneously. This strategy required a centralised Afghan government that could make appointments enticing enough to warlords for them to give up their fiefdoms. The problem with this strategy was that it meant short-circuiting democracy or representative government at a local level. Locals resented appointments from Kabul who didn’t look like them and speak like them. Such resentments could eventually grease the wheels of insurgency.

Time-lines: During his campaign for president, Barack Obama depicted Afghanistan as a good war and Iraq as a bad war. Once he won the White House, Obama made perhaps his greatest strategic blunder: Announcing a timeline for the US military intervention, thereby making the US commitment finite. Rather than convince the Taliban that the insurgency was hopeless, Obama conveyed that they need only hang on, perhaps going to ground for a limited amount of time, and they could outlast the United States. Osama bin Laden famously said that everyone wants to hitch onto the strong horse. Well, Obama convinced the Afghans that the US military was a circus pony that could put on a good show, but ultimately would not last.

The Flipside of COIN: Many military strategists made their careers on counterinsurgency (COIN) and sing its praises. At its core, the idea is to win the hearts and minds of locals and to convince them they are better off working with US-led forces than with insurgents or terrorists. The problem is that COIN proponents often fool themselves into believing they have bought loyalty, when the best they can do is rent it. This was, for example, David Petraeus’s biggest mistake in Mosul, and the reason why the city fell briefly to insurgents in November 2004: He had resourced and promoted insurgents, but confused their cynicism with reconciliation. In Afghanistan, too many US officers believed they could win loyalty when, realistically, Afghan loyalty was never on the table.

The Downside of Development: Both the State Department and the US Agency for International Development often confuse money spent with effectiveness. The problem with flooding an economy like Afghanistan with cash in the guise of development is that it distorts the economy and fans corruption, which can be even more corrosive and widespread than terrorism. If the United States government ever does an honest after-action report about the US engagement in Afghanistan, it should ask the very basic question: Would Afghanistan be any different or even better off absent US development projects?

Pakistan: Trying to end the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan without ending Pakistani support for radical groups is like trying to bail out a boat without first plugging the hole that’s letting in water. Diplomatic niceties – pretending that Pakistan was a partner committed to the same end goals – could not change the reality of Islamabad’s policies and what that meant on the ground. Fantasy is seldom a good basis for counterterrorism policy.

This brings us to the current day. Five thousand or even 10,000 troops will not be enough to do more than stick a finger in the dyke. The questions for the Trump Administration and Congress are first whether they will fully support and fund a US military strategy to defeat the Taliban and deny Afghanistan as an Islamic State foothold and, if not, what the cost of defeat – and an eventual Afghan state collapse – could be to neighbouring countries and to broader US interests. To simply kick the can down the road – as the Clinton Administration did with the Taliban – or acquiesce to Afghanistan’s collapse without thinking through the second and third-order effects, would be as irresponsible as sending troops to Afghanistan in the first place without a long-term, trans-administration commitment to victory.

Dr. Michael Rubin is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute; senior lecturer at the Naval Postgraduate School’s Center for Civil-Military Relations; and senior editor of the Middle East Quarterly. © Commentary magazine (www.commentarymagazine.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Afghanistan/ Pakistan