Australia/Israel Review

A Democratic Momentum

Apr 1, 2005 | External author

Bush’s simple message has worked

By David Pryce-Jones

|

Beirut: “a genuine novelty, an attempt to bring about regime change through non-violent means.” |

Anyone with experience of the Arab Middle East will have found a civilisation that does not know what to do with itself. Freedom and democracy have been unknown quantities. The manners and grace of the past are almost irrecoverable. Creativity is blocked in all spheres by despotisms grinding down everything. One after another, ambitious and ruthless men have seized power and held it on the principle that force is the only law. Most of them have been soldiers, though a few have been monarchs claiming a right to rule through their Islamic affiliations. The coups, wars, and civil wars of these absolute rulers have left innumerable victims. The human waste is tragic. Worse still, the strong oppress the weak and degrade society in a way that cannot be stopped from within, and so would repeat itself forever.

The model of the strong ruler is Gamal Abdul Nasser, far and away the most influential Arab of the 20th century. He had the chance to turn an independent Egypt into a modern nation-state. Instead, he believed that greater strength would come from Arab nationalism. The Arabs are not one people, however, and Arab nationalism set them at each other’s throats rather than uniting them. Nasser compounded his mistake by throwing his lot in with the Soviet Union. Rulers in Syria and Iraq and Libya followed the lead. So did Yasser Arafat. Together they condemned the Middle East to be a bloody arena of the Cold War, and what should have been independent nation-states instead turned into slummy and sovietised dictatorships.

The strength of these dictatorships was more apparent than real, actually a façade behind which the military and secret police were carrying out the dirty work. How strong could any Arab ruler be if the Soviets and the Americans (never mind the Israelis) were stronger? Realisation of weakness has led to pervasive self-pity. Arabs tend to absolve themselves of their failures, blaming them instead on the various Westerners, imperialists, Zionists, infidels, who are so unfairly strong. And out of the painful but unexamined sense of failure has grown Islamism, a religious version of Arab nationalism, positing that Arabs are one people united by their faith, and therefore in no need of nation-states. Fueling Islamism is that same pervasive sense of self-pity that converts into aggression.

Democratisation and the creation of valid nation-states is the only alternative to Arab nationalism and Islamism alike. Democratisation will allow Arabs in each of their countries to take their destiny into their own hands, at last in a position to jettison self-pity and the aggression that springs out of it, and able to meet Americans, Israelis, and everyone else on equal terms. September 11 is the unlikely trigger for democratisation, but such is the cunning of history.

The Islamist challenge

That attack was the moment when the ideology of Islamism superseded an Arab nationalism that was evidently no longer serviceable either as a tool for mobilising Arabs or for rivalling the West. Islamism had been gathering strength since Ayatollah Khomeini seized power in Iran in classic style, and installed his version of a police state. One way or another, Islamist Iran challenged Arabs to emulate it, and Saudi Arabia — and Osama bin Laden in particular — took up the challenge.

Islamism is capable of degrading the Arab world still further, while also taking the West down with it in a way that Arab nationalism could not. Critics like to maintain that Islamism is in the mind, and therefore can only be fought at the intellectual level. On the contrary, the campaign against the Taliban in Afghanistan has shown the positive results of occupying territory. The successful democratisation of an Arab state would refute the pretensions of Islamist ideology, and Iraq is the obvious — perhaps the only — country in which to launch such a process. It has all the resources necessary to become a modern nation-state. Furthermore, the Iraqi Shi’ites and the (non-Arab) Kurds are not Arab nationalists, nor are they Islamists after the Iranian fashion.

Among other immediate benefits, the invasion of Iraq marks the delayed lifting from the Middle East of the Cold War and its consequences. Saddam Hussein was not a Soviet client, to be sure, but he was a faithful pupil of Nasser’s and of Stalin’s. In that role, he sponsored Arafat and the Palestinian intifada. The Israeli-Palestinian struggle is a Cold War relic if ever there was one, and the timely removal of both Saddam and Arafat opens a prospect of negotiations free from the previous considerations of maximising power in the region. The Palestinians themselves are talking about “a real change on the ground.”

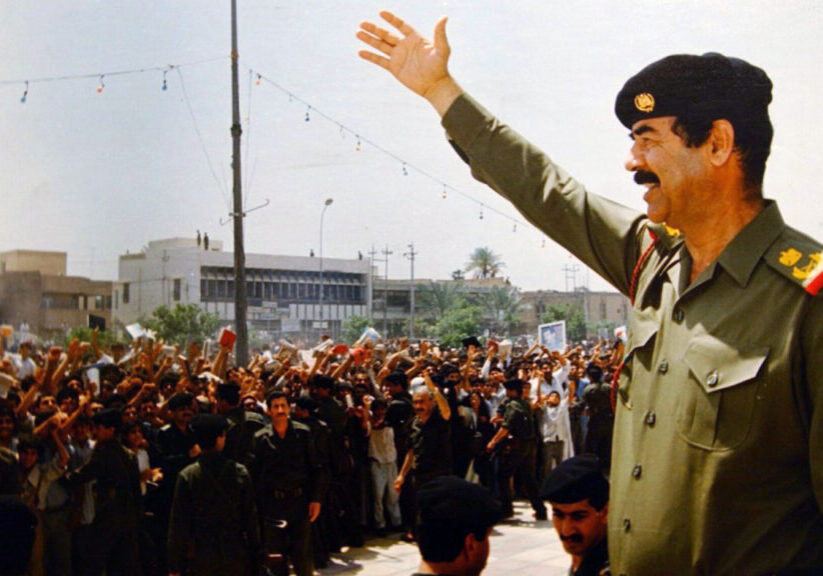

Furthermore, Saddam promoted and justified himself as the very prototype of the Arab strongman. His swift overthrow exposes the fundamental structural weakness of absolutism. Throughout the Middle East, one-man rulers, whether monarchs or presidents, suddenly appear for what they are, fantasists at best, illegitimate tyrants at worst.

And finally the altogether exceptional elections in Iraq have shown that people can begin to take their destiny into their own hands, and so create a nation-state and the freedom that goes with it. In the words of Kanan Makiya, the Iraqi intellectual who has been preeminent in advocating constitutionalism, the Iraqi voters have set the pace because for the first time in any Arab country they have “placed claims on those who will lead them in the future.”

The example proves contagious. The murder of Rafiq Hariri, the former prime minister of Lebanon, was an act of old-style Arab nationalism, perpetrated by someone with the Syrian secret police behind him, maybe President Bashar Assad himself. In former times, this killing would have been shrugged off as the kind of bloody deed characteristic of the region’s politics, and about which nothing could be done, and for which nobody could be brought to account. Hafez, Bashar’s father and predecessor as president, did not hesitate to murder politicians and journalists, including two Lebanese presidents; Kamal Jumblatt, the Druze chieftain; Christian leaders such as Dany Chamoun; and a Sunni chief mufti. Revolted by Hariri’s death but inspired by events in Iraq, the Lebanese are taking to the streets in their tens of thousands for the so-called Cedar Revolution. Although variously Sunni and Shi’ite, Druze and Christian, the demonstrators are united in demanding a nation-state of their own, and the freedom this means.

Walid Jumblatt, leader of the Druze and son of the murdered Kamal, has hitherto taken care to appease Syria. A memorable statement of his shows how far and fast the wind is now blowing: “It’s strange for me to say it, but this process of change has started because of the American invasion of Iraq. I was cynical about Iraq. But when I saw the Iraqi people voting three weeks ago, 8 million of them, it was the start of a new Arab world.” Chibli Mallat, a professor of international law in Beirut and one of the most respected Arab intellectuals, describes events there as a genuine novelty, “an attempt to bring about regime change through non-violent means.”

Compare and contrast the retreat from absolutism under way in the Middle East with the implosion of the Soviet bloc during the late 1980s. In both instances, elections brought an end to monopolies of power. The moment Mikhail Gorbachev allowed Boris Yeltsin to run for office against him, he collapsed his own power base. In Egypt, President Hosni Mubarak has been the sole candidate in four presidential elections. For over twenty years he has ruled by emergency decree, and has never hesitated to use whatever degree of force he has judged necessary to support his power. Muslim extremists and terrorists have been killed or captured and then executed in their thousands. Men of the stature of Saad Eddin Ibrahim and Ayman Nur have been harried and imprisoned for attempting to introduce basic democratic procedures. He seemed to be grooming his son Gamal as successor. Suddenly he is conceding that rival candidates, even Ibrahim and Nur, may stand against him in presidential elections later this year. True, Mubarak receives a $2 billion annual subsidy from Washington, but Bush’s insistence on freedom is evidently forcing first steps in democratisation on him.

In Syria, the constitution was rigged so that Bashar Assad could succeed his father as president, and he has ruled by emergency decree for almost five years. The Cedar Revolution is suddenly demanding that this regime confront its cruelty and corruption. The resources of Syria and occupied Lebanon are in the hands of the Assad family and cronies. Nobody knows the exact tally of Syrian and Lebanese victims. Farid Ghadry, a leading Syrian reformer and an exile, claims that as many as 17,000 people have disappeared. The Syrian prison of Sednaya alone contains more than 600 political prisoners. Aktham Naisse, another courageous intellectual, presented a petition signed by 7,000 Syrians asking for the lifting of rule by emergency decree. Arrested, then released and arrested again, he faces trial. Absolute rulers in Bashar’s predicament make an example of protesters by opening fire on them. Secret policemen recently killed some dozens of Kurdish and other dissidents in Syria, but the scale of the Cedar Revolution precludes a mass atrocity. Pressure from the White House has obliged Bashar to promise to evacuate Syrian troops and secret police from Lebanon. Under this pressure, he complains that he expects an American invasion one day. Put another way, he recognises superior force when he sees it.

|

Iran: the clerics are still ready to shoot as many people as they have to |

What force can do

Is the use of force to break absolutism justified, or is this, as the Left likes to charge, colonialism in contemporary guise? That is the accusation the British once faced as they put down slavery and piracy, and eliminated customs such as the burning of widows in India, seeing no reason to apologise for acts of common humanity. Colonialism is a process full of ambiguity and complexity, springing from some initial inequality between coloniser and colonised. What then evolves with an inflexibility that seems to amount almost to a law of history is that the colonised acquires from the coloniser those ideas and institutions that lead to independence and newfound equality between the parties.

The Iraqi elections, the Cedar Revolution, Mubarak’s concessions, are so many preliminaries toward a more equal relationship between the West and the Arab order. (On a lesser scale, Israel has illustrated the same point by deploying superior force to break Yasser Arafat’s intifada, thereby opening the way to a more equal relationship with Palestinians.) Those threatened with loss of power and dispossession of course may try to recover by mobilising yet more force, or turning to the black arts of deception and lying.

Perhaps Mubarak will somehow manipulate his coming presidential election, for the fifth time arranging a cosmetic vote of more than 90 percent. Perhaps Syrian military and secret police units will leave Lebanon publicly through one door, only to slink back surreptitiously in civilian clothes through another. Muammar Gaddafi has given a fine example of the sort of double-standard conduct to be expected: currying favor with the United States by giving up his weapons of mass destruction, he has made sure that Fathi al-Jahmi, a Libyan democrat and dissident, has vanished without a trace into some prison. Under direct military compulsion to accept loss of power for himself, and freedom for others, Osama bin Laden utters regular long-distance curses. In the same mode, his colleague Abu Musab al-Zarqawi threatens on behalf of the Sunnis of Iraq, “We have declared a bitter war against the principle of democracy and all those who seek to enact it.” The inequality of the relationship they offer could hardly be clearer.

Deception is the time-honoured strategy of poor-little-rich Saudi Arabia. Amid much trumpeting, the country has just held municipal elections, bogus because half the seats were allocated by the royal family; women, of course, were denied the vote. At the same time, in the first seven weeks of this year, there have been twenty public beheadings. Intellectuals presenting a petition for democratic change have been arrested. Nobody knows how many of the Saudi Shi’ites are in prison, or what then happens to them. Dr. Saleh al-Khatham, a Saudi human-rights advocate, says that a third of those arrested are held in prison without trial for over a year. The royal regime will no doubt continue to sponsor terror while pretending to be its victim, and the general helplessness has been recently summed up by Prince Saud al-Faisal, one of the royals who are also ministers, when he said, “We know we want to reform, we know we want to modernise, but for God’s sake leave us alone.”

In grim contrast, the clerics ruling Iran are among the last rulers anywhere in the world with the determination to shoot as many opponents and reformers as they have to on the day that they meet a serious challenge to their absolutism. They are well aware what a mess they have made of government; they swell with the usual self-pity that expresses itself as aggression. Blaming their faults on the United States, they see themselves waging undeclared war against the Great Satan of their imagination. Again nobody really knows the scale of the daily injustices the population suffers, but the victims of judicial executions and arbitrary imprisonment are in the tens of thousands. Huge numbers of Iranians — almost certainly the majority — are in a state of proto-rebellion and look to the United States to liberate them.

The dark shadow of these clerics falls over their Arab neighbours, and it may have the power to scupper current hopes, and check democratisation at least for the time being. The Iraqi elections were a setback for them, true. But Syria is their proxy, and it has proxies in turn, Hezbollah and Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Hezbollah is the largest and best-organised militia in Lebanon, capable both of frustrating American interests through terror and of disrupting Palestinian-Israeli negotiations. Commanding Hezbollah in Lebanon, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah is already calling for mass rallies to support Syria and so perpetuate the old Arab order; whereby the strong do what they like to the weak. He warns, “This is a year of devotion to resistance.” Another year or two is all the mullahs need to acquire the nuclear weapon, which is their version of an equal relationship with the United States. Should they succeed, another much more unstable Cold War will settle on the Middle East.

![]()

David Pryce-Jones is the author of The Closed Circle: An Interpretation of the Arabs, and over 20 other books. © National Review (www.nationalreview.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iraq