Australia/Israel Review

Why Israel’s quest for a unity government failed

Dec 18, 2019 | Ahron Shapiro

Following the September 17 election in Israel, which left no clear path to a majority coalition for either of the 120-seat Knesset’s two largest factions – Binyamin Netanyahu’s Likud Party (32 seats) or Benny Gantz’s Blue and White (33 seats) – it initially appeared that, for the first time since the 1980s, a unity government was in the offing.

Indeed, with Avigdor Lieberman’s Yisrael Beitenu party (eight seats) effectively holding the balance of power and refusing to support any other outcome, it seemed to really be the only option.

The fact that a unity government did not eventuate was a result of a conflicting web of conditions that each major party placed on entering into such a partnership. Like an unsolvable logic exercise, every possible political combination led to a dead end. The only hope was for one or more parties to compromise on their demands. That didn’t happen, and that is why Israel is now heading for its unprecedented third round of elections in less than a year.

Immediately following the September election, Netanyahu formed a bloc of all religious parties and most right-wing parties with the exception of Yisrael Beitenu – including the Likud, Shas (nine seats), United Torah Judaism (seven seats), Jewish Home (four seats) and the New Right (three seats).

While this 55-seat bloc fell significantly short of a Knesset majority, by refusing to join any coalition that would not include all of these other parties, Likud forced Blue and White (B&W) to choose between two bad options: either going second in a leadership rotation within a right-wing-dominated unity government under Netanyahu’s unyielding terms, or pursuing narrow left-wing government that would require the outside support of both the predominately Arab Joint List (13 seats) and its nemesis Yisrael Beitenu.

While either option would have likely spelled political suicide for B&W in the event of future elections, the second option was probably never attainable as Yisrael Beitenu and the Joint List loathe each other. While Lieberman initially claimed he was prepared to punish any side that refused to compromise for unity by forming a government with its opponent, it later became clear this was a bluff – he was not prepared to be in any government that was either backed by the Joint List, or included the ultra-Orthodox parties, Shas and United Torah Judaism.

By mid-November, Lieberman was vociferously denouncing the Joint List as a “fifth column” and “enemy from within” that “doesn’t represent the Arabs of Israel.” Meanwhile, at least some of the MKs in the Joint List also ruled out supporting any government that included Lieberman, even from the outside.

With Netanyahu holding firm on his demands to keep his bloc together and go first in any leadership rotation agreement, Lieberman also had the option of joining a coalition of right-wing and religious parties similar to the one he left a year ago and rejected after the April 2019 election. Again, while initially hinting he might be open to such a coalition in order to pressure Gantz, Lieberman later ruled out this scenario in the strongest terms on account of his rejection of the policies of the ultra-Orthodox parties, whom he derided as “non-Zionist” and coercive.

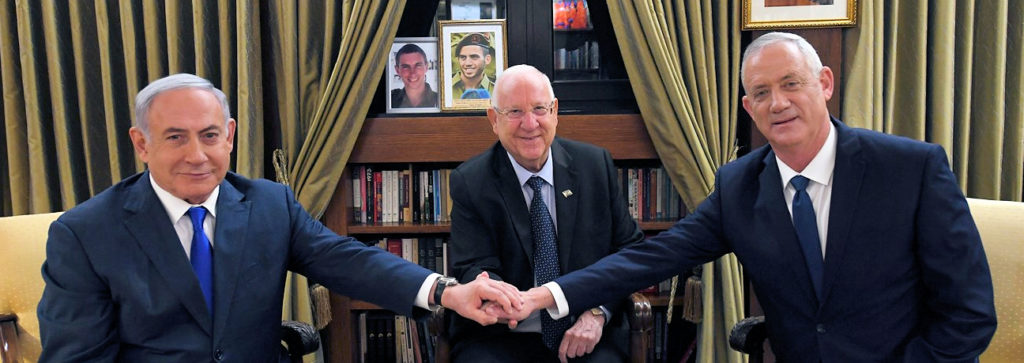

Meanwhile, even before the final votes had been counted in the election, President Reuven Rivlin had begun pushing a plan whereby Netanyahu would declare himself incapacitated to serve as PM due to his corruption indictments, but retain the title and trappings of prime minister for the duration of his trial. Meanwhile, Gantz would serve as acting prime minister and become full prime minister after two years under a leadership rotation arrangement.

However, Gantz faced strong resistance from within B&W against accepting any scenario where Netanyahu would be allowed to go first in a prime ministerial rotation regardless of the circumstances – partly out of principle and to fulfil pre-election pledges, but also due to fears of betrayal.

The scope of Netanyahu’s “incapacitation” and the curbs on his powers were also reportedly points of contention with Likud negotiators, with Gantz reportedly telling confidantes in early December that his distrust of Netanyahu had only increased over the course of coalition talks.

Attorney-General Avichai Mandelblit’s announcement on Nov. 21 that the state had decided to formally indict Netanyahu on various corruption charges across three separate cases only strengthened B&W’s resolve not to serve in any Netanyahu-led government while he was under indictment.

With the understanding that Netanyahu’s criminal cases present the largest impediment to forming a coalition in time to avoid a third election, Israel’s Channel 12 reported on Dec. 4 that Rivlin had said he would consider pardoning Netanyahu in exchange for the PM admitting wrongdoing and then retiring from politics.

Rivlin would not confirm the report and in any case, there has been no indication that Netanyahu, who has previously angrily dismissed the charges against him as a “legal coup”, would be prepared to accept such an arrangement.

Mid-December party preference polls show virtually no shift in voter allegiances since the Sept. 17 election.

There thus appears to be little hope currently that Israel’s third election in a year will bring the country any closer to breaking the stalemate, as long as the current political actors continue to hold firmly to their incompatible demands.

Tags: Israel