Australia/Israel Review

The search for a new IAEA Director General

Sep 3, 2019 | Tzvi Fleischer and AIJAC staff

On Monday July 22, Japanese diplomat Yukiya Amano passed away following an illness. When he died, Amano was in his 10th year as the Director-General (DG) of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), an organisation also known as the UN’s nuclear watchdog.

A few days later, the IAEA Board of Governors (BOG) appointed Romanian Cornel Feruta as acting Director-General. Feruta, also a career diplomat, had served as Chief Coordinator of the IAEA since 2013, and had effectively acted as Amano’s chief of staff.

This development now positions Feruta as a front runner for the top job in the upcoming elections to be held during the annual IAEA meeting, currently scheduled for Sept. 16-20. Another reported candidate for the job is Argentina’s Ambassador to the IAEA, Rafael Grossi.

The IAEA is the body entrusted with implementing both sides of the equation which constitute the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). A cornerstone of international security, the NPT is based on a bargain between the countries that had nuclear weapons at the time and those that did not – the former would supply nuclear energy technology for peaceful purposes to the latter at reasonable costs, while the latter agreed to never pursue atomic bombs. The IAEA hence helps countries to set up civilian nuclear projects and at the same time is in charge of monitoring these programs to ensure they are not “diverted” to military uses and are safe to run.

The person heading the IAEA must be a successful administrator, responsible for more than 2500 professional staff of different nationalities spread across at least 100 countries. Based on their work, the DG authorises and signs official reports, including those dealing with countries that are possibly breaching the NPT (“non-compliance”) and are using their civilian nuclear infrastructure as a front for nuclear weapons development.

Iran and the IAEA Director-General

In the first half-decade of the 21st century, the exposure of Iran’s illicit nuclear program, aimed at producing several nuclear bombs, greatly boosted the international profile for the IAEA’s director-general, up until then a relatively obscure, technical and non-political role.

At the time, Amano’s predecessor as director-general, Egyptian Mohammed ElBaradei, courted controversy with his handling of the Iranian nuclear file. The agency’s reports about Iran under ElBaradei were somewhat self-contradictory. On the one hand, very suspicious and problematic concerns were noted by the inspectors on the ground in Iran – and these concerns were strengthened by intelligence findings based upon stolen Iranian files which made it into the public domain. On the other hand, “forgiving” and positive expressions, minimising the importance of these concerns, appeared in the more political parts of the reports summarising the overall conclusions, as overseen by the DG.

Mohamed ElBaradei

It was clear from repeated statements by ElBaradei warning against military strikes on Iran that his overwhelming preoccupation was to prevent IAEA reports being used as justification for military action against Iran, with the 2003 US invasion of Iraq repeatedly mentioned as the precedent he was trying to prevent from recurring.

Media reports at that time alleged that IAEA technical staff were “unhappy with top-level decisions to declare issues clarified without what they deemed to be sufficiently credible explanations from Iran” (though these reports were unsurprisingly denied by ElBaradei’s spokespeople).

ElBaradei went out of his way several times to publicly insist that there was no evidence Iran was seeking to build nuclear weapons.

In fact, the technical findings in IAEA reports provided ample evidence that they likely were, and material which has come to light from the Iranian nuclear archives captured by Israel last year confirms that this was indeed the Iranian goal.

Eventually, even ElBaradei could not prevent the IAEA Board of Governors from determining in 2005 that Teheran was in “non-compliance” with its NPT commitments, which triggered sanctions against Iran imposed by the UN Security Council through a series of resolutions.

Amano replaced ElBaradei in December 2009, and was chosen in part on the premise that he would help correct the politicisation introduced by ElBaradei into IAEA reporting, and focus on making fact-based non-political judgements on emerging nuclear threats, specifically Iran (and also North Korea).

And he initially appeared to succeed in doing so, with little controversy over his tenure for his first five years in the job.

But then came the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran (JCPOA) – a game-changer which pushed Amano into a difficult position.

IAEA officials participated alongside European, American and Russian representatives in the negotiations with Teheran on that deal. Among the Agency staff involved in the negotiations was acting DG Feruta, who was Amano’s chief of staff at the time and remains today a strong advocate for the deal.

This involvement by the IAEA in the negotiation process inevitably created an investment by the organisation in the success of the agreement.

The IAEA and the JCPOA

A key milestone of the IAEA’s role in the JCPOA process came at the end of 2015. The JCPOA set a requirement for Iran to assist the IAEA in issuing a final report on the Possible Military Dimensions (PMD) of the Iranian nuclear program by late 2015 in order for the main provisions of the deal to be implemented.

Amano and the IAEA were thus under pressure to close the investigation into what Iran did in the past – and is still doing today – to produce a nuclear bomb, or the JCPOA could not go ahead.

Amano issued his report in December 2015. It stated that “The Agency has found no credible indications of the diversion of nuclear material in connection with the possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear programme”.

Yet the analysis of the details of that IAEA final report into PMD, undertaken by the Institute for Science and International Security, an independent NGO led by former weapons inspectors, makes it clear that the IAEA was not given enough information by Iran to reach this conclusion. The Institute noted that, across 12 questions about areas of alleged past military dimensions of the Iranian program identified by the IAEA, the IAEA’s own report made it clear that Iranian responses were often simple denials or grossly inadequate attempts to assert that Iran’s action related to the area of concern was completely compliant without providing either access or evidence.

Worse, the IAEA’s assessments about the 12 alleged elements of Iran’s military nuclear program was not conclusive in 10 of the 12 issue areas, and only partially conclusive in the other two. Yet the IAEA nonetheless went on to certify, in effect, that all questions about the military dimensions of Iran’s nuclear program were now resolved and the file on PMD could be closed.

Critics charge that the conclusions of that report reflected the IAEA’s determination, in order to preserve the JCPOA process, to find a way not to render a highly critical judgment of Iran’s past activities or call attention to Teheran’s almost total lack of cooperation in the present concerning requirements to fully disclose all of its past illegal work.

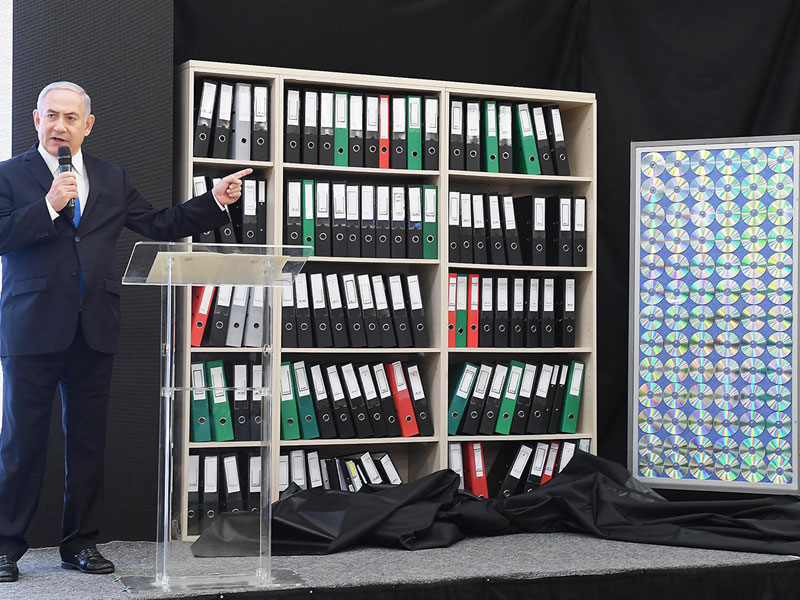

The Iranian nuclear archives seized by Israel last year show IAEA knowledge of Iran’s military nuclear efforts is incomplete

Moreover, the material found in Teheran’s secret nuclear archive stolen by Israel in late January 2018 appears to prove that there were large portions of Iran’s military nuclear activities that the IAEA knew little or nothing about in 2015.

The JCPOA effectively means that the IAEA, having signed off on the PMD issue in the December 2015 report, can no longer investigate “Past Military Dimensions” of Iran’s nuclear program.

And the agency anyway seems reluctant to fully implement its inspection powers in the post-2015 period to avoid the risking upsetting the JCPOA apple cart. In 2017, when the US Trump Administration was pushing the IAEA to do more to inspect Iranian military sites, one senior IAEA official told Reuters they would not push for such inspections in the face of Iranian resistance because, “If they [the Trump Administration] want to bring down the deal, they will… We just don’t want to give them an excuse to.”

The deal authorised the IAEA to issue periodical reports on the implementation of the agreement and Iran’s adherence to its technical terms.

However, these reports have greatly reduced details when compared to the pre-JCPOA reports. Post-JCPOA reports often consist of a single page asserting Iran has not violated limitations on enrichment or number of centrifuges, with no further details on the exact amount of enrichment undertaken or what the IAEA had done to confirm this information.

Pre-JCPOA reports generally ran to dozens of pages and had extensive details to support claims made.

As the Institute for Science and International Security noted regarding the first post-JCPOA IAEA report on Iran:

“This is the first IAEA report in years that does not provide an inventory of near 20 percent LEU [low enriched uranium] in Iran, and provides a vague inventory, and no production details, for the amount of less than 5 percent LEU. The lack of data and information in the report make it impossible to make any independent determination of Iran’s compliance. By failing to provide more information about the status of key technical aspects of Iran’s nuclear program and the implementation of its JCPOA commitments to date, the IAEA is withholding vital data about the status of Iran’s nuclear program. It risks undermining public transparency and confidence in the agreement.”

There has been little change to this pattern of very limited reporting in subsequent IAEA reports on Iran in the years since then.

The change is apparently due to the IAEA’s interpretation of provisions of the JCPOA, especially clause 74, as well as subsequent IAEA-Iran agreements (which are themselves not public), as requiring them to keep all information collected about Iran confidential.

As Israeli academic proliferation experts Emily Landau and Efraim Asculai (the latter a former IAEA official) have pointed out :

“Although the JCPOA that was presented to the public in 2015 was hailed as the most transparent arms control agreement ever reached, as far as the public domain is concerned, the JCPOA, in reality, signaled the start of a problematic and puzzling reduction in transparency as to Iran’s nuclear activities and plans for the future. This stems from the confidentiality that Iran was granted per the JCPOA in its dealings with the IAEA.”

The US Withdrawal and Subsequent Events

In May 2018, the US withdrew from participation in the JCPOA nuclear deal, heavily criticising it and imposing strong new sanctions on Iran.

In the period since then, analysis of the Iranian secret nuclear archive seized by Israel has begun to reveal in great detail ongoing and past breaches of the NPT and the JCPOA.

The IAEA has apparently responded slowly to the new intel, despite documents from the archive being delivered directly to its experts. For example, it took the Agency almost six months to visit a warehouse in Teheran that was publicly named by Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu in September 2018 as the location where Iran had allegedly stored 15 kg of enriched uranium and a variety of undeclared nuclear equipment until a month earlier. The delay enabled the Iranians ample time to try and cleanse the site of any incriminating evidence.

Still, according to reports in the Israeli media, IAEA inspectors did pick up radioactive residues inside the warehouse. But months have elapsed since the IAEA last inspected the site in March, and so far, no official public IAEA document or statement has addressed this revelation, which may very well indicate another breach of the JCPOA by Iran.

With Iran now openly not complying with key elements of the nuclear deal, some proliferation experts are arguing it is now essential to rethink the IAEA’s approach to monitoring Iran – particularly the unwillingness to continue exploring the past military dimensions of the program, especially in the wake of the Israeli revelations, and the complete secrecy the IAEA continues to maintain about both its findings in monitoring Iran and what the IAEA itself is doing to ensure that Iran’s efforts are peaceful.

For instance, Landau and Asculai urged last year that, in the wake of Iran’s threat to withdraw from elements of its obligations under the JCPOA (and Iran has subsequently made good on these threats, strengthening Landau and Asculai argument):

“The grounds for Iran’s confidentiality rights must be reconsidered, and indeed, removed. As such:

The IAEA reports on Iran must return to their previous format, including full information regarding Iran’s nuclear activities and plans for the future, and full reports, including results, on all the inspections that were carried out at military facilities. Since January 2016 (Implementation Day), the reports have excluded all of this information.

All the deals that were concluded between the IAEA and Iran must be made public. It is unacceptable, for example, that the public only learned through investigative reporting over the course of 2016 that Iran has plans to install and operate thousands of advanced centrifuges from year 11 of the deal. This kind of information is crucial for informed debate about the value of the JCPOA and for informed assessments of Iran’s intentions in the nuclear realm.

Reports on deliberations in the context of the Joint Commission (that oversees the JCPOA) and the Procurement Working Group (that is meant to discuss intelligence regarding Iran’s efforts to illicitly procure technologies and components relevant to a weapons program) must be made public.”

The IAEA is now at a crossroads. The tragic death of Amano opens the door for a new kind of leadership that would navigate the agency back to the status it enjoyed in the past as an almost universally respected “watchdog”.

The Nobel Committee explained their decision to award the IAEA with the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize in 2005 by noting that “In the nuclear non-proliferation regime, it is the IAEA which controls that nuclear energy is not misused for military purposes, and the director-general has stood out as an unafraid advocate of new measures to strengthen that regime.”

For the sake of that international campaign against nuclear proliferation, it is to be hoped that next director-general will move the IAEA away from its current adherence to a very narrow, politicised interpretation of its role within the JCPOA, and restore the IAEA’s role with respect to Iran as the central, neutral watchdog under the NPT.