Australia/Israel Review

Essay: The Soldier and the Lawyer

Sep 25, 2009 | Col. Richard Kemp CBE

International law and asymmetrical operations in practice

By Col. Richard Kemp CBE

I will examine the practicalities, challenges and difficulties faced by military forces in trying to fight within the provisions of international law against an enemy that deliberately and consistently flouts international law.

I shall focus on counter-insurgency operations from the British and to some extent the American perspective drawing on recent British experience generally and my own personal experience of operating in this environment.

Soldiers from all Western armies, including Israel’s and Britain’s, are educated in the laws of war.

Commanders are educated to a higher level so that they can enforce the laws among their men, and take them into account during their planning.

Because the battlefield – in any kind of war – is a place of confusion and chaos, of fast-moving action, the complexities of the laws of war, as they apply to kinetic military operations, are distilled down into rules of engagement.

In the most basic form these rules tell you when you can and when you cannot open fire.

In conventional military operations between states the combat is normally simpler and doesn’t require complex and restrictive rules of engagement.

Your side wears one type of uniform, the enemy wears another; when you see the enemy’s uniform you open fire. Of course there are complexities. The fog of war – sometimes literally fog, but always fog in the sense of chaos and confusion – means that mistakes are made. You confuse your own men for the enemy.

We call it blue on blue, friendly fire or fratricide.

Civilians perhaps taking shelter or attempting to flee the battlefield can be mistaken for combatants and have sometimes been shot or blown up.

But in the type of conflict that the Israeli Defence Forces recently fought in Gaza and in Lebanon, and Britain and America are still fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, these age-old confusions and complexities are made one hundred times worse by the fighting policies and techniques of the enemy.

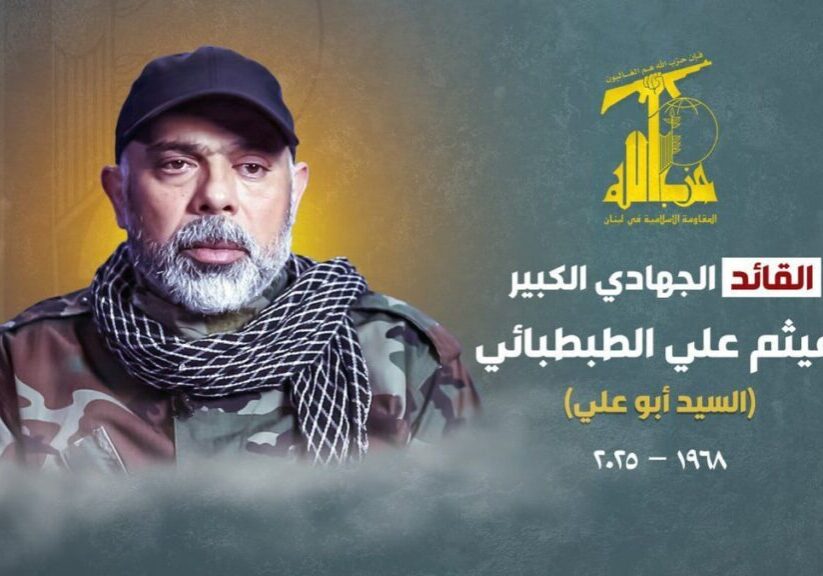

The insurgents that we have faced, and still face, in these conflicts are all different. Hezbollah and Hamas in Israel, al-Qaeda, Jaish al-Mahdi and a range of other militant groups in Iraq. Al-Qaeda, the Taliban and a diversity of associated fighting groups in Afghanistan. They are different but they are linked.

They are linked by the pernicious influence, support and sometimes direction of Iran and/or by the international network of Islamist extremism.

These groups, as well as others, have learnt and continue to learn from each others’ successes and failures.

Do these Islamist fighting groups ignore the international laws of armed conflict? They do not. It would be a grave mistake to conclude that they do. Instead, they study it carefully and they understand it well.

They know that a British or Israeli commander and his men are bound by international law and the rules of engagement that flow from it. They then do their utmost to exploit what they view as one of their enemy’s main weaknesses.

It is not simply that these insurgents do not adhere to the laws of war. It is that they employ a deliberate policy of operating consistently outside international law. Their entire operational doctrine is founded on this basis.

In Gaza, as in Basra, as in the towns and villages of southern Afghanistan, civilians and their property are routinely exploited by these groups, in deliberate and flagrant violation of any international laws for both tactical and strategic gain.

Stripped of any moral considerations, this policy operates simply and effectively at both levels.

On the tactical level, protected buildings, mosques, schools and hospitals, are used as strongholds allowing the enemy the protection not only of stone walls but also of international law.

On the strategic level, any mistake, or in some cases legal and proportional response, by a Western army will be deliberately exploited and manipulated in order to produce international outcry and condemnation.

And in sophisticated groupings such as Hamas and Hezbollah, the media will be exploited also as a critical implement of their military strategy.

Thus in April 2004, as Coalition forces fought to wrest the Iraqi town of Fallujah from al-Qaeda’s control the media reports screamed of a US bombardment of a mosque.

The reality of that day was that five US Marines were wounded by fire from that mosque and that the Marine commander on the ground exercised great care and restraint, only allowing fire to be directed upon the outer wall of the building.

Despite this, the damage was done and the impression that we had levelled a mosque indiscriminately was firmly established.

In Gaza, according to residents there, Hamas fighters who previously wore black or khaki uniforms, discarded them when Operation Cast Lead began, to blend in with the crowds and use them as human shields.

We have of course seen all this before, in Lebanon, in Iraq and in Afghanistan.

Today, British soldiers patrolling in Helmand Province will come under sustained rocket, machine-gun and small-arms fire from within a populated village or a network of farming complexes containing local men, women and children.

The British will return fire, with as much caution as possible.

Rather than drop a 225-kilogram bomb onto the enemy from the air, to avoid civilian casualties, they will assault through the village, placing their own lives at greater risk. They might face booby traps or mines as they clear through.

When they get into the village there is no sign of the enemy. Instead, the same people that were shooting at them twenty minutes ago, now unrecognised by them, will be tilling the land, waving, smiling and talking cheerfully to the soldiers.

Like Hamas in Gaza, the Taliban in southern Afghanistan are masters at shielding themselves behind the civilian population and then melting in among them for protection.

Women and children are trained and equipped to fight, collect intelligence and ferry arms and ammunition between battles.

I have seen it first hand in both Afghanistan and Iraq. Female suicide bombers are almost commonplace.

Schools and houses are routinely booby-trapped. Snipers shelter in houses deliberately filled with women and children. Every man captured or killed is claimed as a taxi driver or a farmer.

The British and US armies have grappled with these problems and I hope that we are now finding some solutions. Solutions that allow us to treat those that oppose us according to the laws of war while also defeating them on the battlefield. When an enemy flouts the rules of war then we cannot shy away from hard decisions.

Let me quote from the US military counterinsurgency manual, recently produced under the direction of Gen. Petraeus and using lessons from Iraq and Afghanistan. This pretty much encapsulates the approach that we use as well as that used by the Americans.

“The principle of proportionality requires that the anticipated loss of life and damage to property incidental to attacks [that is, to non-combatants] must not be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage expected to be gained. Soldiers and marines may not take any actions that might knowingly harm non-combatants.

“This does not mean they cannot take risks that might put the populace in danger.

“In conventional operations, this restriction means that combatants cannot intend to harm non-combatants, though proportionality permits them to act, knowing some non-combatants may be harmed.”

Under our equivalent of Gen. Petraeus’ doctrine, when necessary British forces now attack protected locations after weighing up the risk that non-combatants might suffer. We respect international norms and the sanctity of holy places. However, when our troops take fire from these locations or roadside bombs stored there are used to murder the innocent, we have no choice other than to act.

British and American troops now routinely search mosques in Afghanistan and Iraq and when necessary we bring down fire on those locations. This is not done, or should not be done, in a trigger-happy or careless manner but rather in a proportionate way and always with the aim of minimising wider suffering.

Ultimately, in counter insurgency operations the military commander must balance a series of often conflicting and very difficult judgements in addition to the other pressures he faces on any battlefield. The balance is between firstly achieving the mission by engaging and killing the enemy, secondly, avoiding civilian casualties and thirdly, the effect on hearts and minds – the support or otherwise of the civilian population.

There is a fourth judgement as well, often overlooked in media and human rights groups’ frenzies to expose fault among military forces fighting in the toughest conditions. The fourth is preventing or minimising casualties among your own soldiers. There will frequently be times when a military commander must make a snap judgement between the safety of his own troops and that of other people.

Human nature dictates that he will often choose his own men. It is hard to see how it could be otherwise. And there is more to it even than the commander’s human nature and loyalty to his men. For soldiers to follow their commander into combat – at any level, but especially at the point of battle – they must trust him. No soldier will trust, or follow, a commander who is profligate with his men’s lives.

Let us not forget that these calculations, judgements and decisions are not taken in an air-conditioned office or from the safety of a rearward military headquarters.

As a commander you are surrounded by your men yet totally alone.

You have to kill the enemy knowing that you will then need to shake hands and win the consent of the family in the compound that he is occupying. You haven’t slept for two days, you are shattered, you are wet with sweat and the chaos of battle reigns all about you.

There are no computers, on your map with your pen you must compute the locations and intentions of the enemy, your flanking forces, and your own troop positions.

You must do this immediately because the CO needs a situation report, your company needs a briefing to orient them, and your fire support team commander is about to bring in fast air, helicopters and mortars, and needs to know that the dangerous close fire missions are not going to kill your own men. You must assess the situation and give the go in seconds to secure the initiative.

The only advantage to the commander of all this is that it makes you forget the eighty pounds on your back, the water in the ditch that is up to your waist, and the sweat and dirt that streams constantly into your eyes.

Every soldier who has been in combat – whether it is Gaza, Lebanon, Afghanistan or Iraq – can testify to the chaos and confusion of war.

These realities apply to any combat situation and the challenges they add are self-evident. But they become that much harder when fighting a tough, wily, skilful enemy, one minute shooting at you or setting a landmine to blow up your vehicle, the next leaning on the threshold of his compound, smiling at you, dressed indistinguishably from the population.

Gen. Stanley McChrystal, the new US commander of forces in Afghanistan, has said the reduction of unnecessary civilian casualties is one of his top priorities. It should be. That is also a high priority of British commanders in Afghanistan.

I have personally witnessed the efforts that American forces have been making for years in Iraq and Afghanistan to minimise civilian deaths. These have been impressive, but of course they have not always worked in either of our armies.

There is also another factor that we shouldn’t forget. There will always be bad soldiers who deliberately or through incompetence go against orders.

I have spoken of the considerable British and American efforts to operate within the laws of war and to reduce unnecessary civilian casualties. But what of the Israel Defence Forces? The IDF face all the challenges that I have spoken about, and more. Not only was Hamas’ military capability deliberately positioned behind the human shield of the civilian population and not only did Hamas employ the range of insurgent tactics I talked through earlier. They also ordered – forced, when necessary – men, women and children, from their own population to stay put in places they knew were about to be attacked by the IDF. Fighting an enemy that is deliberately trying to sacrifice their own people. Deliberately trying to lure you into killing their own innocent civilians.

And Hamas, like Hezbollah, are also highly expert at driving the media agenda. They will always have people ready to give interviews condemning Israeli forces for war crimes. They are adept at staging and distorting incidents.

Their people often have no option than to go along with the charades in front of the world’s media that Hamas so frequently demand, often on pain of death.

What is the other challenge faced by the IDF that we British do not have to face to the same extent?

It is the automatic, pavlovian presumption by many in the international media, and international human rights groups, that the IDF are in the wrong, that they are abusing human rights.

So what did the IDF do in Gaza to meet its obligation to operate within the laws of war? When possible the IDF gave at least four hours’ notice to civilians to leave areas targeted for attack.

Attack helicopter pilots, tasked with destroying Hamas mobile weapons platforms, had total discretion to abort a strike if there was too great a risk of civilian casualties in the area. Many missions that could have taken out Hamas military capability were cancelled because of this.

During the conflict, the IDF allowed huge amounts of humanitarian aid into Gaza. This sort of task is regarded by military tacticians as risky and dangerous at the best of times. To mount such operations, to deliver aid virtually into your enemy’s hands, is to the military tactician, normally quite unthinkable.

But the IDF took on those risks.

In the latter stages of Cast Lead the IDF unilaterally announced a daily three-hour cease-fire. The IDF dropped over 900,000 leaflets warning the population of impending attacks to allow them to leave designated areas. A complete air squadron was dedicated to this task alone.

The IDF phoned over 30,000 Palestinian households in Gaza, urging them in Arabic to leave homes where Hamas might have stashed weapons or be preparing to fight. Similar messages were passed in Arabic on Israeli radio broadcasts warning the civilian population of forthcoming operations.

Despite Israel’s extraordinary measures, of course innocent civilians were killed and wounded. That was due to the frictions of war that I have spoken about, and even more was an inevitable consequence of Hamas’ way of fighting.

By taking these actions and many other significant measures during Operation Cast Lead the IDF did more to safeguard the rights of civilians in a combat zone than any other army in the history of warfare.

But the IDF still did not win the war of opinions – especially in Europe. The lessons from this campaign apply to the British and American armies and to other Western forces as well as to the IDF.

We are in the era of information warfare. The kind of tactics used by Hamas and Hezbollah and by the Taliban and Jaish al Mahdi work well for them. And they will continue to use them.

How do we counter it? We must not adopt the approach that because they flout the laws of war, we will do so too. Quite the reverse. We must be and remain – whiter than white.

There are three lines of attack.

First, we must allow, encourage and facilitate the media to have every opportunity to report fairly and positively on us and on our activities. This requires positive and proactive, not defensive and reactive, engagement with the media. We should bring the media into our training, let them get to know our units before battle, bring them in whenever possible during combat.

There are risks in all this, big risks which are self evident and do not need to be spelt out. But we must be brave enough to take those risks.

Second, we must show the media in a way they cannot misunderstand the abuses perpetrated by the enemy. Our own units must identify such enemy abuses, and make statements about them, backed up by the hardest available evidence.

Third, we must be proactive in preventing adverse media stories about our own units. I am not talking here about distorting the facts. We must look ahead and identify potential problem areas – preferably before they arise. We must have what the British Labour Party used to call rapid rebuttal units.

They should have the ability to establish the facts on the front line very, very quickly. Be absolutely sure of the facts, and ensure they are pushed rapidly to the media. If they are not one hundred percent sure of the facts, they must say as much.

Where real problems do occur, where our troops are in the wrong, if possible we should say so as quickly as we can, driving the agenda, pre-empting the shrieks of the enemy or of the UN.

Where there is genuine concern over our own troops’ conduct or action, we must not hesitate to conduct enquiries and investigations, and if necessary bring people to justice.

But this involves of course yet another major complication – because we must not confuse mistakes made as a genuine consequence of the chaos and fog of war with deliberate defiance of rules of engagement and the laws of war.

Mistakes are not war crimes. We must also know how to explain this.

Most armies do some of these things already. But what we need really is a radical re-evaluation of the effort required to achieve the impact we need. This requires a mind-set that is hard to find in most armies around the world. It requires extra resources and a shift in priorities. And it significantly complicates already highly complex military operations.

It does not answer all of our problems by any means. But all the steps I have mentioned are – in my view – essential to countering the strategies and tactics of the insurgents we are faced with today – in Gaza, Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere.

Colonel Richard Kemp, CBE, served in the British Army from 1977 to 2006. He was Commander of British Forces in Afghanistan in 2003, and was subsequently attached to the Cabinet Office, where his responsibilities included Iraq, and he made several visits to Baghdad, Fallujah and Mosul. The above is excerpted from his address to the Joint International Conference on Hamas, The Gaza War and Accountability under International Law sponsored by the Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs (JCPA) on June 18. © JCPA, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Israel