Australia/Israel Review

Editorial: Frustration versus Analysis

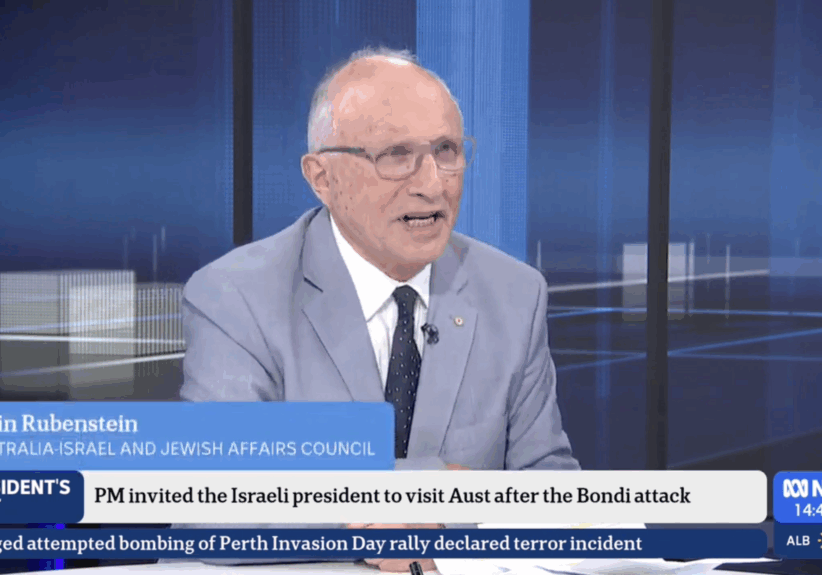

Mar 26, 2010 | Colin Rubenstein

Colin Rubenstein

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict provokes frustration because the general outline of a reasonable resolution is hardly unknown: Two states with a Palestine in Gaza and the majority of the West Bank and land swaps with Israel to make up any differences; a Palestinian capital in or around Jerusalem; special arrangements for the holy places; the Palestinian refugee problem resolved with compensation and resettlement outside Israel. Israel would receive an end to further Palestinian claims, and arrangements to provide security both from hostile armies based in the new state as well as rocket attacks and cross-border terrorism.

Yet, although the resolution appears very clear, progressing there is desperately, exasperatingly difficult. Unfortunately, the well-meaning but relatively inexperienced Obama Administration has shown a counter-productive tendency to act out of this frustration rather than careful analysis.

It did this last year, when it publicly demanded from Israel a complete and total freeze on all building past the 1949 armistice lines.

And it did so again this March when it chose to dramatically escalate a diplomatic hiccup following a genuine Israeli mistake in a poorly-timed, low-level announcement of one stage of planning approval for new housing in Jewish eastern Jerusalem during Vice President Joe Biden’s visit.

The first miscalculation led to a major setback in efforts to restart Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas is involved in what is essentially a civil war with the rejectionist, Iranian-supported Hamas, which constantly seeks to paint him as a traitor. Abbas could not possibly demand less than Washington without severe repercussions among Palestinians. So he made a total building freeze everywhere a precondition for talks – although no such precondition had ever existed during frequent Israeli-Palestinian talks since 1993.

But the public demand from Washington was completely politically unrealistic in Israel. It is impossible to imagine any Israeli government of any complexion agreeing to the freeze demanded in Jerusalem, Israel’s capital, the eastern part of which was formally annexed in 1967. Compromise on Jerusalem is probably possible in a full, genuine peace treaty. Asking Israel to behave today as if it agreed that all the eastern parts of the city – including the major Jewish holy sites and many large Jewish neighbourhoods just outside the CBD – are rightfully Palestinian land, is not.

Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu did in November implement a ten-month moratorium on all new home-building in the West Bank excluding Jerusalem, which Hillary Clinton rightly said was “unprecedented.” But facing important local elections next June, the Palestinian Authority still refused to renew talks, until eventually, after considerable US and Arab state pressure, acceding to “indirect” talks, a huge step backward compared to the past 17 years.

Now, the latest American explosion of indignation over the Jerusalem announcement has apparently made even these indirect talks doubtful.

Despite the frequent focus on them, settlements are simply not the major obstacle to future peace. Since 2003, in agreement with the American government, Israel has had policies in place that prevent new settlements being established or any outward expansion of existing settlements. Arguments that recent internal growth in settlements precludes future Palestinian statehood are simply unsustainable.

Further, no conceivable Israeli concessions or peace offers can make a final Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement likely in the near future. Israeli public opinion consistently supports a peace arrangement along the lines noted above, provided they are convinced that the Israeli requirements will be met. Israel’s three major political parties, Likud, Kadima and Labor, all support a two-state resolution.

Israel has repeatedly acted on this consensus – offering reasonable two-states deals that would fulfil the above criteria under Barak in 2000-2001, and even more generously under Olmert in 2008. Furthermore, in 2005, Israel completely withdrew from Gaza. Unfortunately, the result was an immediate escalation of rocket attacks into Israel from Gaza, and the eventual takeover of Gaza by Hamas. A repeat of this situation in the West Bank would potentially make normal life impossible for most of the Israeli population.

Palestinians are today divided between Hamas in Gaza, and the often corrupt and ineffectual Fatah in the West Bank. Even if Mahmoud Abbas were to sign a peace deal with Israel, he cannot deliver Hamas and Gaza, nor can he even guarantee to bring the West Bank with him.

Moreover, Palestinian statehood will not, as is often assumed, in itself automatically bring Israel the benefits of peace by satisfying Palestinian aspirations, because statehood has never been the central goal of secular Palestinian nationalism, much less of Islamist groups like Hamas. Thus, Israel cannot rely on statehood in itself to satisfy Palestinian aspirations, and so must have both security guarantees and a Palestinian leadership able to credibly enforce them. That last condition does not exist today.

Furthermore, American public spats with Israel tend to bring out the worst in Palestinian politics. Palestinians have always been susceptible to the illusion that statehood should simply be provided to them as of right, without negotiations or compromises. Mahmoud Abbas clearly indicated this tendency last year in an interview with the Washington Post. Public American efforts to pressure Israel reinforce the already strong tendency among Palestinian leaders to believe that their aspirations can be attained by simply persuading America to force Israel to give it to them. However, this is not a viable path to peace.

Washington should instead be seeking to capitalise on recent incremental progress in the West Bank in terms of governing institutions and economic growth. This means insisting on renewed Israeli-Palestinian talks and resolving any disagreements with the Israeli government in ways which do not feed Palestinian illusions that they can avoid compromise and negotiations, or create Israeli public doubts regarding Washington’s commitment to support Israeli security. However it also means recognising that final peace is probably not achievable at the moment given the state of Palestinian politics, and the need to instead pursue interim arrangements that can bring that outcome closer.

Tags: Israel

RELATED ARTICLES

Security concerns over Herzog visit a terrible indictment: Joel Burnie on Sky News

Allegations against Israeli President Herzog are absurd: Colin Rubenstein on ABC News