Australia/Israel Review

Nothing Personal: The US-Israeli relationship

Feb 26, 2013 | Andrew Friedman

Andrew Friedman

US President Barack Obama could hardly have picked a more auspicious time for his presidential visit to Israel. It is a time when both the American and Israeli governments are in flux – both he and Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu were recently re-elected. Both leaders are in the midst of selecting new cabinet secretaries, government ministers and senior advisory teams for their new terms in office, and both men can be assumed to be trying to commit themselves to smoothing over personal differences in favour of continued strategic cooperation. And all this is occurring at a time when the rate of flux in the wider Middle East – in Syria, in Egypt, in Jordan, in the Persian Gulf, and in terms of the pace of Iranian nuclear progress – has never been higher.

AIR correspondent Andrew Friedman caught up with Professor Eytan Gilboa, Director of the School of Communications at the Begin-Sadat (BESA) Centre for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University and an expert on US-Israel relations, for an exclusive briefing about the presidential visit, the state of US-Israel ties and how these relate to general US policy in the Middle East.

Both President Obama and Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu have been re-elected, but their support teams have changed. Obama has new secretaries of state and defence, as well as a new national security adviser. Here in Israel the government is in flux while the coalition negotiations are progressing, but there will be major changes. How will the changes impact US-Israel ties?

I think this visit is an opportunity for both leaders to discuss the strategic relationship, and to turn a new page in our bilateral relations, which are based on joint needs, threats and issues of concern around the Middle East. Certainly, during Obama’s first term, their personal chemistry wasn’t good, but that didn’t affect strategic cooperation, which is the most important part of international relations. The leaders may not like each other, and they appear to not really trust each other, but they’ve got to learn to work together. The issues and threats that both countries face – Iran, Syria, Egypt, Palestinian issues – are very serious. The whole Middle East is in turmoil, and this visit will be an opportunity to talk about these threats and the possible responses to them.

You mentioned the Palestinians. Some observers have suggested that the President is coming to Israel to jump start a return to negotiations. What’s your view?

Of course, the President will make a strong case for resuming talks with the Palestinians, but I don’t believe this will be a central focus of the visit. I think the visit’s got more to do with garnering public opinion in Israel – he wants to build a consensus here to let the United States deal with the Iranian nuclear program and with Syria. But in order to do that, he’s got to talk directly to Israelis.

You mentioned that President Obama and Prime Minister Netanyahu had a cool personal relationship during the President’s first term. The perception that Netanyahu supported Republican challenger Mitt Romney can’t have helped that, and some commentators here have predicted that Obama will now seek revenge on Netanyahu. Possible?

I cannot say strongly enough how much I feel that this statement is incorrect, for two main reasons: first of all, you don’t make policy decisions based on personal revenge. Secondly, it does not at all line up with Obama’s personality.

I heard a story recently, from a very senior US official. The official said “you know, we’ve got strong relationships with many countries, places like Great Britain and Canada. But we benefit most from our ties with Israel. We get terrific return on our investments, in terms of intelligence sharing, weapons systems research, military doctrine and more.”

Over the past few years, opponents of Israel (and even some Israeli opponents of Prime Minister Netanyahu) have tried to argue that Israel has become a burden to the US. But it’s absolute nonsense. The opposite is demonstrably true, and strategic cooperation remains excellent. The leaders may disagree on some key issues, but officials on both sides say that Israel is a highly valuable strategic asset, especially with the turmoil and instability in the region.

Two years ago, Robert Satloff of the Washington Institute told me that for all of Obama’s change of tone from President Bush, his efforts to improve America’s image in the Muslim world had not paid off. As he begins his second term, do you see any signs that he’s learned some lessons about the Middle East?

It’s hard to say. On one hand, you’ve got Vice-President Biden talking tough to the Iranians – the Administration has offered to open direct talks, but emphasised that if Teheran wants to talk, the negotiations will have to be serious and in good faith. Biden spelled out for them that “serious” means “ready to make some compromises”. So that’s a good sign.

But there are other, more worrying signs. The appointments and nominations he’s made since the beginning of the year – John Kerry as Secretary of State, Chuck Hagel as Secretary of Defence, Susan Rice as Ambassador to the UN – all these suggest that the Administration still believes that all problems can be resolved if only we’re nice enough. That’s a problematic approach in this area of the world, as we saw immediately with Iran’s response to Biden’s offer for direct talks – they responded with a pre-condition that Washington must recognise Iran’s right to develop its nuclear program, and that Washington must repeal the sanctions against Iran. To me, that says that Iranian officials understood these appointments as an expression of weakness in Washington.

There are other areas of this apparent confusion in Obama’s foreign policy, too. He [found it] easy to let [former Egyptian President Hosni] Mubarak go, because he had such high expectations for the revolution that toppled him. Now, he’s become a bit more realistic about [current President] Mohammed Morsi and the seriousness of the challenges to be faced in the Arab world.

But at the same time, Obama still thinks Turkey is a good model for Islamic democracy. But over the past two years, Ankara has slipped steadily towards Islamic dictatorship – there are more journalists in Turkish prisons today than in Chinese ones. How could that be model for emerging democracies in the Arab world?

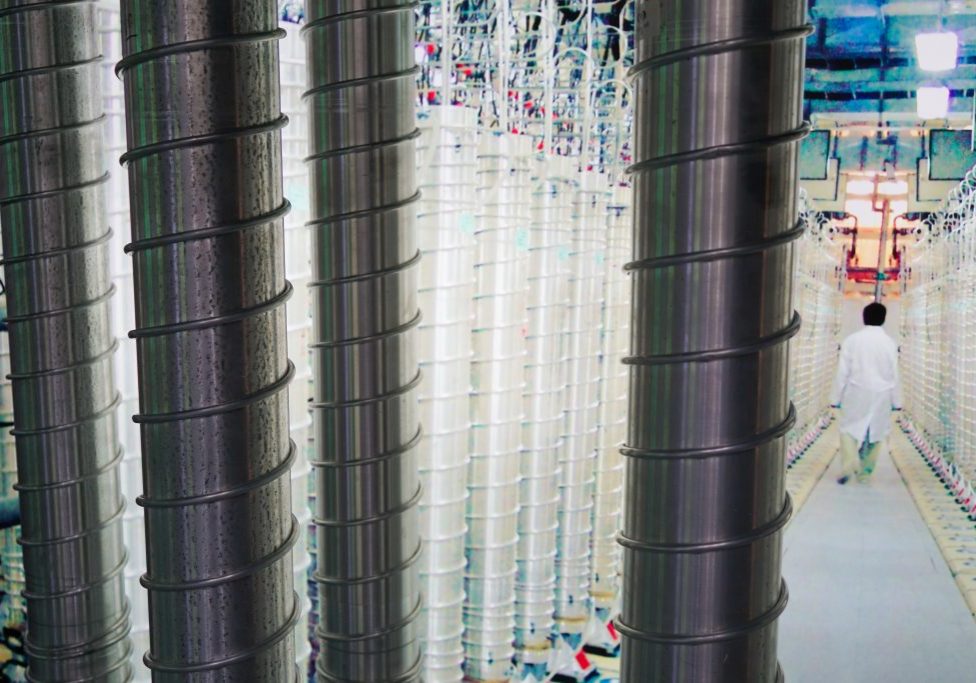

You mentioned Iran and potential talks over Teheran’s nuclear program. It is clear that Israel does not possess the military wherewithal to destroy the program as thoroughly as Iraq in 1981 or Syria in 2007. Could Washington accomplish that goal? Does Washington have the political will to do so?

In military terms, there is no question that the United States has the capability to destroy Iran’s nuclear facilities. At the very least, Washington could deal a significant blow to Iran’s aspirations for nuclear technology and for missiles.

Whether or not the Americans have the political will to do that is another matter. The American public is tired of fighting, after a decade in Afghanistan and Iraq. Obama’s strategy is to force Iran to change directions by inflicting heavy economic damage, by forcing them into negotiations and to get an agreement that would delay their search for a bomb.

Now, Obama believes the sanctions are working, Netanyahu believes they aren’t. The interesting thing is that both are right, because the sanctions regime is a two-stage policy. Stage one is to create financial hardships in Iran, and that has happened, as per Obama. But those hardships have not yet yielded concrete policy changes from the Ayatollahs, so on that count, Netanyahu is right.

Still, there is a chance we could see serious US-Iran negotiations, but my concern would be that the talks would create a vague agreement that would allow the sides to say “Iran is a legitimate partner to prevent nuke proliferation in the region,” but that it would also leave room for Iran to continue creating a nuclear bomb.

All of which leads back to the upcoming visit: President Obama has an idea that the United States should “lead from behind”, but I think that’s an oxymoron. You either lead, or you will be left behind. During Obama’s first term, reality refused to behave the way he wanted it to. Now, he’s going to have to develop new strategies and a new outlook to take in the new realities in the region. If he does that, Israel then becomes a significant factor as a source of ideas and an instrument for Israel and America to accomplish their joint national interests.

Tags: International Security