Australia/Israel Review

Essay: A Lapse into Seriousness

Mar 25, 2013 | Daniel Meyerowitz-Katz

A UN report shows what could have been

Daniel Meyerowitz-Katz

Few outside of certain circles would be aware that a draft of the report by the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (‘OHCHR’) to the UN Human Rights Council (‘HRC’) on last year’s Gaza conflict was released in March.

Any report that the HRC releases on Israel should immediately arouse suspicion – it is not without reason that Israel is currently refusing to participate in any of the HRC’s functions. Indeed, January’s report to the HRC from the “International Fact-Finding Mission on Israeli Settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory” – the commissioning of which was the original impetus for Israel to boycott the Council – transpired to entirely vindicate Israel’s decision. As has become standard practice for such reports, the “Fact-Finding Mission” channeled the form of justice practised by Lewis Carroll’s Queen of Hearts: “Sentence first – verdict afterwards.”

The terms of reference stated the conclusions that the Mission would reach, requiring the Mission only to re-hash the usual accusations to substantiate its predetermined conclusions.

Nevertheless, this new report seems to have been released with an unusual lack of fanfare, barely making a headline before it slipped into obscurity.

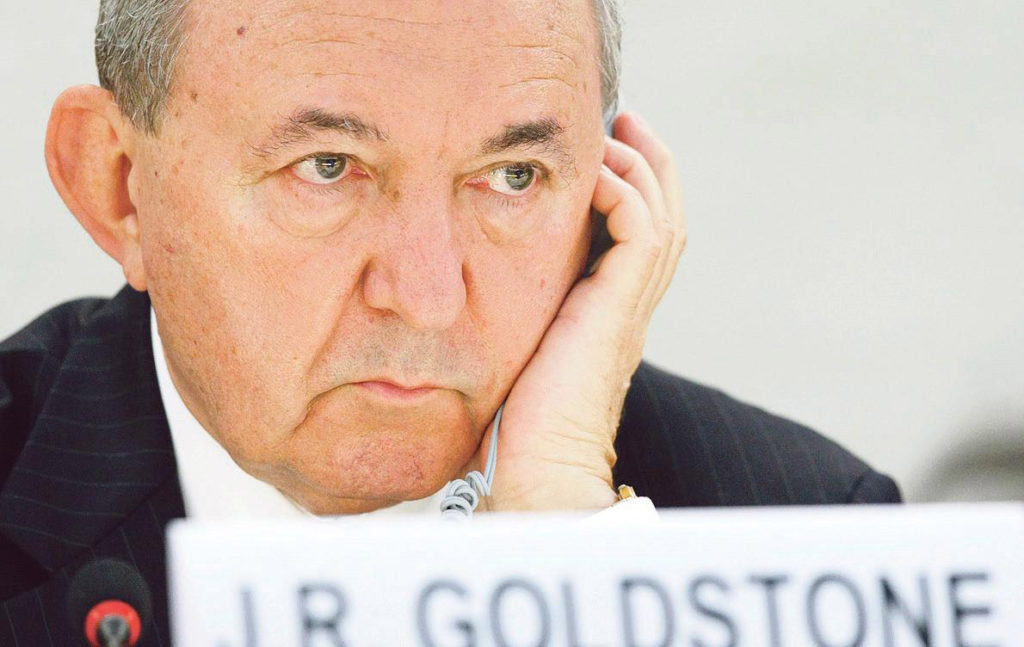

This is in stark contrast to the reaction met by its predecessor, the infamous “Report of the UN Fact-Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict”, commonly known as the “Goldstone Report”, concerning the conflict in Gaza at the end of 2008. The Goldstone Report provoked years of outrage. In its wake came an almost relentless barrage of criticism directed at Israel for alleged breaches of international law, as well as vehement and detailed refutation by a considerable body of opponents who utterly rejected the report’s findings.

After 18 months of diplomatic hostilities, the debate around the Goldstone Report reached the most definitive ending that such debates can have, when the report’s namesake Richard Goldstone distanced himself from its findings. Nevertheless, the report remains a mainstay of the anti-Israel discourse, and continues to be the “go-to” document for those trying to prove Israel guilty of war crimes.

Spot the difference

So why such different reactions for what, on the surface, should be very similar reports?

Before even opening one of the reports, anyone comparing the two would notice a glaring distinction: the OHCHR report numbers 17 pages in total; its predecessor reaches 452. Even factoring in that Operation “Cast Lead” went for about three times as long as Operation Pillar of Defence, or that it caused just under ten times as many casualties, the earlier report’s length is staggering in comparison. The discrepancy is explained by the entirely distinct approaches taken by their respective authors.

The new report has largely identified individual instances of allegations that could potentially amount to breaches of international law, drawing largely from on-the-ground monitoring by the OHCHR. It identifies a number of legal obligations that may have been breached; details observations made by OHCHR, giving other sources where relevant; then discusses to what extent a particular allegation may amount to a legal breach.

In contrast, the Goldstone Report follows a format familiar to anyone in the legal profession: it sets-out the facts of a particular case, then sets out the law, and finally applies the law to the facts in order to make a “finding”. This is the format of a judgment. As Goldstone himself later noted, he was leading a fact-finding mission and not conducting a trial. The tone of the report, therefore, was very misleading.

The difference can be easily seen through comparing the styles of language employed. For example, here is one of the conclusions from the Goldstone Report:

“Israel displayed a premeditated determination to achieve the objective of destruction. It is, therefore, responsible for the internationally wrongful acts it perpetrated in breach of the duties specified above.”

Importantly, Israel had refused to cooperate with the Mission as it refused to give legitimacy to what it saw as an enquiry whose very purpose was to find Israel guilty. This means that the Mission never heard Israel’s case with respect to any of the incidents investigated. It goes against every principle of justice to find a party guilty without even hearing its side of the case, yet Justice Goldstone seemed to have had no qualms in “finding” that Israel had illegal and malign objectives.

The more recent report took a very different tone. For example:

“OHCHR, while gathering information, was not able to identify any military objective that the IDF might have had in these cases, thus raising concerns with regard to possible violations of the principle of distinction and potentially also the right to life.”

In other words – and in stark contrast to Goldstone – this report actually acknowledges the limitations of the information available. It notes that there is a possibility of illegal acts, but that Israel may have been justified if there were a military objective of which the OHCHR was not aware.

Relevantly, Goldstone also acknowledged in his retraction of his report that Israel had conducted investigations into the incidents the report had raised and taken appropriate action. That is the ideal outcome of such reports. International courts are only supposed to become relevant where there is a failure of domestic legal systems to enforce international law. Conversely, Goldstone also noted that no investigations had been conducted by Hamas for the handful of accusations made against them.

Unlike the Goldstone Report, the tone of the new report is in keeping with the obvious objective of facilitating additional investigation and legal action where warranted.

Looking for facts?

The relative paucity of accusations against Hamas in the Goldstone Report is itself revealing of the Goldstone Mission’s questionable approach. For example, Chapter VIII of the report deals with the responsibilities during the conflict of Palestinian armed groups. One very common sentence in this section, not found elsewhere in the report, is “the Mission did not investigate this case and is unable to make a determination in regard to the allegations.” Particularly revealing is where, in the section on Hamas’ potential failure to distinguish its combatants from the civilian population, the Mission notes “that only one of the incidents it investigated clearly involved the presence of Palestinian combatants”. In that incident, the combatants were in uniform and could be distinguished from civilians.

It is not clear how exactly the Mission managed to investigate a three week conflict between Palestinian armed groups and Israel, generating a 452-page report, and only identify a single incident involving Palestinian combatants. There certainly seems to have been no shortage of incidents to investigate involving Israeli combatants.

In fact, the report refers to multiple incidents which clearly involved Palestinian armed groups, some of which are mentioned below. It just fails to acknowledge them as such. (Unless, of course, it was not clear to the Mission that there were Palestinian combatants involved in those other incidents because the Commission had difficulty distinguishing the combatants from civilians.)

The report concludes by saying that the Mission “found no evidence that members of Palestinian armed groups engaged in combat in civilian dress. It can, therefore, not find a violation of the obligation not to endanger the civilian population”. Readers who skipped the small print and went straight to the conclusions (after all, how many could be bothered to read all 452 pages?) would have no idea that it was less a case of “not finding” evidence as deliberately ignoring it; with the relevant section full of the “no investigation… no determination” formulation noted above.

On the other hand, the recent OHCHR report appears much more willing to acknowledge the obvious. For example, over the course of three paragraphs (37-39), the OHCHR discusses Palestinian armed groups launching attacks from within civilian areas. Paragraph 37 identifies five individual instances of rockets being launched close to civilians. The next paragraph notes that launching attacks from populated areas violates the legal obligation to take all precautions to protect civilians. Paragraph 39 then outlines instances of these rockets falling short of their targets and killing civilians in Gaza, and notes that the limited military capacity of the Palestinian groups is no justification for failing to take measures to avoid civilian casualties.

In one of incidents mentioned, a rocket fell short and killed the baby son of BBC photographer Jihad Masharawi. Ironically, a photograph of a distraught Masharawi cradling his dead son became a symbol for those accusing Israel of “war crimes”. In setting the record straight on this tragedy, the report, to some extent at least, demonstrated that the UN is capable of useful fact-finding from a neutral source.

In contrast, the Goldstone Report spends 14 paragraphs (446-460) discussing the same issue in the earlier conflict. The Mission indicates that it spoke to two people who witnessed the launching of rockets from civilian areas, one of whom gave vague details about rockets launched from “a narrow street and from a square in Gaza City without providing further details”, and the other of whom mentioned that rockets “may have” been fired from a certain neighbourhood. None of these incidents were identified by the Mission as involving “Palestinian combatants” – at least for the purposes of determining whether the combatants had adequately distinguished themselves from the civilian population. Perhaps the Goldstone Mission believed these rockets simply fired themselves.

Referring to these incidents and some allegations in various NGO reports, the Goldstone Mission went on to claim that launching rockets from civilian areas would only be illegal if the armed groups were conducting these attacks specifically to shield themselves with the civilian population. This also stands in contrast to the law as interpreted by the OHCHR, whose report made it clear that there was a duty to “take all feasible measures” to avoid civilian casualties.

The Goldstone Mission then mentions that a Palestinian Islamic Jihad (‘PIJ’) fighter told the International Crisis Group that PIJ “stay away from the houses if [they] can” – which, the Mission claimed, “suggests the absence of intent”. It went on to dismiss Hamas’ open online bragging about operating from within civilian areas on the basis that “some websites of Palestinian armed groups might magnify the extent to which Palestinians successfully attacked Israeli forces in urban areas” (emphasis added).

Essentially, the Mission absolved Hamas of crimes that Hamas itself bragged about committing, and gave PIJ the benefit of the doubt when a single representative said that the organistion was doing its best. Where Israel was concerned, however, the Mission said that Israel’s numerous efforts to minimise civilian casualties were “inadequate”, and rejected the many statements from Israeli officials that they were only attacking military targets and any civilian casualties were inadvertent.

Apparently, a single second-hand statement from an anonymous Islamic Jihad fighter was regarded as more credible than any assurance that any Israeli official could offer.

A new direction?

This is not to say that the new OHCHR report is without its flaws. One particularly obvious flaw is that the report’s writers could not bring themselves to use the word “Hamas” to describe the regime in Gaza, instead choosing the acronym “DFA” for “De Facto Authorities.” Additionally, the spectre of Goldstone does surface occasionally – such as where the report expresses doubt that an Israeli strike on Hamas’ broadcasting equipment could offer a “military advantage”, despite noting that Israel had stated its intention to target “Hamas operational communication sites.”

Still, the OHCHR has produced what is perhaps the fairest and most objective report on Israel in the history of the HRC (including its predecessor, the Human Rights Commission). It is imperfect, but is certainly leaps and bounds ahead of both the Goldstone’s Missions effort and the HRC report that triggered Israel’s disengagement from the Council.

It is not clear whether the report’s uncharacteristic fairness is an anomaly or the beginning of a new trend. It could be that Israel’s tactic of shunning the Council in its entirety is paying some dividends. Perhaps some of the Council professional staff are finally trying to rid it of the pervasive anti-Israel taint that helped bring down the Human Rights Commission and is currently threatening to do the same to the current HRC.

It would be a major step forward for both the UN as a body, and for Middle East peace prospects, if UN human rights organs were finally heading towards some much-needed legitimacy. Their politicisation has badly damaged the UN’s global credibility as an impartial and trustworthy institution, particularly where the Israeli-Arab conflict is concerned. Only time will tell if this report marks a welcome real change in the HRC’s approach, or simply a rare lapse into seriousness and professionalism from a body long characterised by neither.

Tags: Israel