Australia/Israel Review

Russia, China and the Middle East

May 28, 2013 | Amotz Asa-El

Amotz Asa-El

The era of bad feeling that once governed Israel’s relations with the eastern superpowers has been over for nearly a quarter-of-a-century.

Having exchanged ambassadors in the aftermath of the Cold War with both Moscow and Beijing, the Jewish State’s trade with the two has since grown exponentially, as China became a major client of Israeli technology and Russia a major supplier of Israel’s oil. Politically, too, a live-and-let-live spirit evolved, as Russia allowed its Jews to emigrate and both powers backed the Oslo Accords.

The new practicality that came to govern these relations endured even the two powers’ growing disputes with Washington last decade, over human rights, trade practices and other issues. Now, however, the ongoing Middle Eastern upheaval has re-positioned the two as strategic thorns in Israel’s side.

The good news is that, this time around, the disputes are devoid of the Communist era’s vitriol and recrimination. The bad news is that the interests at stake are simply incompatible, and will remain such as long as Russian and Chinese understanding of the world in general, and the Middle East in particular, does not undergo thoroughgoing change.

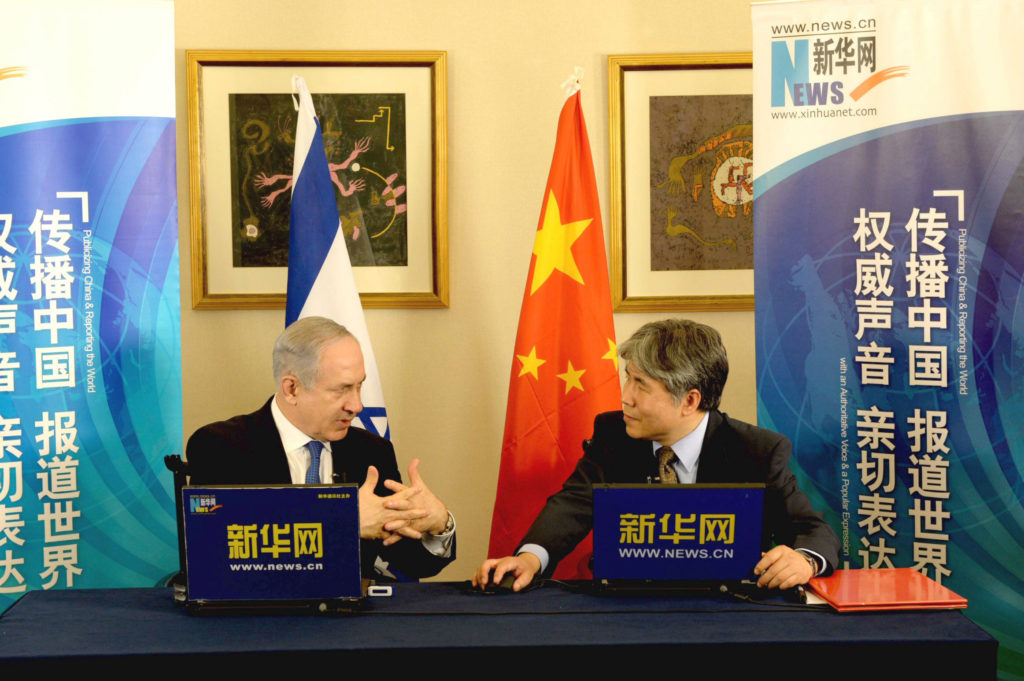

The severity of the challenges Moscow and Beijing now pose to Israel was dramatised in May during Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s visits to both capitals. In China, Netanyahu tried to convince President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Li Keqiang that China would do well to join the international community in defining Teheran’s nuclear program as a threat to international trade. In Russia, Netanyahu reportedly tried to persuade President Vladimir Putin to suspend a contracted sale of highly-advanced S-300 anti-aircraft missiles to Syria.

Both Russia and China politely turned Netanyahu down.

Much has been said since the Arab upheaval’s eruption about the anti-Western reflexes, especially of Russia, but also in Beijing. Pundits agree that this is not imaginary, especially in the wake of the the downfall and death of longtime Russian client Muammar Gaddafi following NATO’s bombing campaign in Libya. From Russia’s point of view, that outcome was overkill, so-to-speak. Russia cannot afford to be seen around the Third World as impotent in the face of Western efforts to remove its protégés, especially when the televised removal is so dramatic and violent.

And since Bashar Assad is a Russian client even more than Gaddafi was, his survival has become for Moscow a strategic aim in its own right. However, Russia also has another, more direct, reason for clinging tenaciously to the Assad regime, one that harks back to Tsarist geo-strategy.

In line with its quest since the days of Peter the Great, Russia craves outlets to so-called warm waters. In the aftermath of the Cold War, Moscow’s only permanent non-Russian seaport is in Tartus, in the southern part of Syria’s short coastal strip, just north of Lebanon. Russian vessels have been anchoring there for decades, and thousands of Russian professional have been stationed in Syria with their families as part of this presence.

Though the civilian part of this presence has been drastically reduced in the wake of the civil war, the military presence remains intact, as does the political commitment behind it. It is, in effect, the continuation of an old saga that began in the 19th century, when Tsarist Russia built elaborate churches in Jerusalem, and then continued the following century, when the USSR invested heavily in Egypt’s Aswan Dam.

Tartus, therefore, is for Russia a strategic asset of the first order under any leadership, but even more so under the nationalist Putin. The Assad regime knows this full well, and knows even better that Moscow cannot assume that a non-Alawite regime would allow it to retain this precious foothold. That is why Russia is helping preserve the Assad regime in disregard of international misgivings.

China’s case in the Middle East is entirely different. Lacking any religious sentiment or imperial history in the region, the only interest that Beijing now sees in the Near East is commerce. And in this regard, its designs are shaped by its unquenchable thirst for the minerals with which the region is endowed.

And since the Chinese are thinking for the long-term, they view Iran as an intrinsic energy supplier, so much so that there has been talk of a trans-Asian pipeline between the two. China’s current oil consumption of more than 6 million barrels per day is expected to exceed 10 million by the end of this decade; hence the Chinese refusal to confront Iran.

And this refusal, in its turn, means allowing Iran’s major ally, Bashar Assad, to retain power, and also refraining from joining the West in calling him to task for the atrocities that his army has been committing for more than two years.

China has not been altogether hostile to the boycott effort. Last year it decreased its imports from Iran to the maximum allowed by the US without risking American commercial retaliation. However, China is already the world’s largest oil importer, having just surpassed the US in this category, and the way Beijing sees the world, its oil suppliers are entitled to their own foreign policies, provided of course those do not threaten China.

This is a stance that has nothing to do with Israel’s conduct, reflecting an impartiality that is expressed in the brisk trade taking place between Israel and China, currently amounting to an annual US$8 billion. That is also why China’s newly installed President and Premier hosted Netanyahu for a very high-profile, full-week visit that was not even dented by Israel’s reported action in Syria the day before Netanyahu landed in Beijing.

Faced with the Russo-Chinese inflexibility, Israel has formulated a policy of “red lines”.

In Iran, the red line is well known – military nuclear capability. In Syria it is the transfer of game-changing weaponry to Iran’s Lebanese proxy, Hezbollah. That is why, reportedly, Israeli warplanes struck twice within 24 hours in early May outside Damascus, where Iranian-made long-range missiles had reportedly arrived in order to proceed to South Lebanon, where they would have threatened Israel.

The Israeli message, therefore, is believed to be: Jerusalem takes no sides in Syria’s civil war, but it will not allow sophisticated Syrian weaponry, least of all chemical weapons, to reach organisations like Hezbollah.

Ironically and tellingly, Beijing condemned Israel for its attack while Netanyahu was visiting, but the wording of the Chinese statement was mild and it did not dent Netanyahu’s trip, either in terms of its busy itinerary or the welcoming atmosphere.

The Chinese attitude, therefore, seems clear: Beijing will trade with anyone and fight with no one among the Middle East’s many antagonists and their assorted patrons.

Russia’s attitude is less clear. Unlike China, it is in a position to unseat Bashar Assad almost overnight as he cannot survive without Russia’s military assistance and diplomatic backing. Signs that Russia is considering such a move have emerged repeatedly. For instance, Moscow did not respond to the Israeli action in May. And in April, after Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi’s visit to Moscow, there were reports that Putin asked his guest permission to build a naval base in return for a US$2 billion loan. Such a base could replace Tartus. Neither part of the deal is known to have led anywhere.

Following the visit of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Erdogan to the White House on May 16 and 17, there is renewed talk of an international effort to remove Assad with Russian acquiescence, so the bloodshed in that country can end, and a process of national reconciliation can begin. Then again, while Russia can afford Assad’s departure, Iran’s mullahs cannot.

For now, Western hopes that Russia would accept Assad’s removal in return for retaining Tartus remain elusive. While American, European and Turkish denunciations of Assad intensified, Russia has multiplied it naval presence in the Eastern Mediterranean and also piled obstacles in the path of perspective peace conference in Geneva, insisting that Iran take part in the forum, an idea that France has already formally rejected and the US is equally unlikely to accept.

In the meantime, what can be assumed with fair certainty is that whenever the post-Assad era arrives, and whatever else it features, it will include a Russian naval base somewhere around the Mediterranean, and Chinese trading posts everywhere.