Australia/Israel Review

Israel’s diplomatic spring

Aug 5, 2016 | Amotz Asa-El

Amotz Asa-El

Half-a-decade after its foreign relations seemed on the verge of a historic crisis, Israel faces a diplomatic spring.

The crisis began with the erosion last decade of the alliance with Turkey, and was then redoubled in the wake of the upheaval in the Arab world on the one hand, and Iran’s diplomatic gains on the other.

The setback in Turkey followed its secular establishment’s loss of power for the first time since the republic’s establishment following World War I – a transition that resulted in Ankara’s refusal to allow the US to use bases on Turkish soil to invade Iraq.

At the same time, Turkish leader Recep Erdogan began attacking Israel using rhetoric and theatrics Jerusalem had never heard previously from Ankara – most memorably in 2009 when Erdogan stormed out of a panel with then-president Shimon Peres in Davos, Switzerland, in protest at Israel’s fighting at the time in Gaza.

The following year Turkey fully abandoned its alliance with Israel after Turkish activists clashed with Israeli troops while trying to breach Israel’s naval blockade of Gaza, which had been spewing rockets at Israeli towns. Nine Turks were killed in that confrontation, after attacking the IDF commandos who boarded the boat to divert it to the Israeli port of Ashdod.

Turkey’s consequent downgrading of diplomatic ties with Israel to a minimal level was underpinned by the disappearance of the two countries’ once elaborate military cooperation, including brisk arms sales and joint aerial and naval manoeuvres.

Worse, Erdogan was openly cheering and fanning the bellicosity of Israel’s implacable enemies, both the Shi’ite Hezbollah in Lebanon, and the Sunni Hamas in Gaza.

Israel had hardly adjusted to this new reality in 2011 when street rioters in Egypt unseated President Hosni Mubarak, with whom Jerusalem had a constructive, if quiet, rapport. Egypt soon elected Islamist Mohamed Morsi, who had equated the Jews to apes and pigs.

Coupled with Iran’s ongoing threat to annihilate the Jewish state, and with its growing international legitimacy as talks over its nuclear program evolved, Israel was faced simultaneously with hostile and confident governments in Cairo, Ankara and Teheran.

It was an unprecedented, and ominous configuration.

Turkey recognised Israel as early as 1949, the first Muslim country to do so, and Iran followed suit in 1950, when it stationed an envoy in Jerusalem. By the 1960s, relations matured as a regional alliance of pro-Western non-Arabs emerged, involving Jerusalem, Teheran and Ankara as well as Addis Ababa.

This structure later fell apart, as Ethiopia became Marxist and Iran became Islamist, but Israel’s loss of Iran had been offset by the peace it signed with Egypt.

Israel, in short, had always had at any given time at least two friends within the Turkish-Iranian-Egyptian triangle. In 2012, however, all three were at odds with the Jewish state.

Four years on, the tables have turned.

The sharpest change has happened in Ankara. Following more than five years of complex negotiations, Turkish and Israeli diplomats finalised a deal to fully restore diplomatic ties, in what is clearly part of a broader Turkish retreat from its so-called neo-Ottoman orientation.

Erdogan’s quest to restore Turkey’s historic role in the Middle East as the foundation of Turkey’s place in the world has failed resoundingly in the wake of the Arab civil wars. Burdened with 3 million Syrian refugees while sustaining occasional rocket attacks from Syrian towns and fending off suicide bombers infiltrating from Syria and Iraq – Erdogan realised Israel is not his natural enemy, and its friendship can be useful.

Moreover, having found itself at loggerheads with Russia in the wake of its downing of a Russian fighter jet last year, Turkey felt dangerously dependent on Russian gas. Israel’s newly discovered gas fields in the Mediterranean thus became a natural alternative. Hence the Turkish quest to end its crisis with Jerusalem.

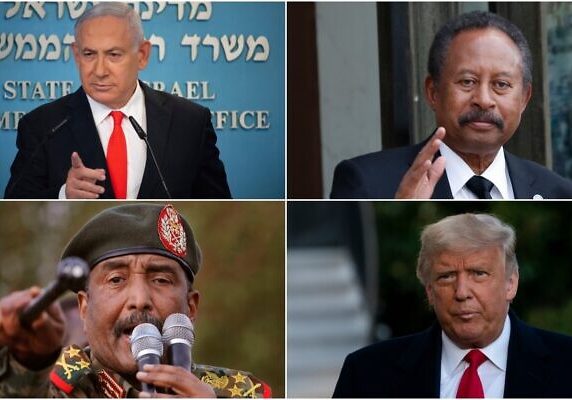

The deal itself is a piece of diplomatic art. Ignited by an Israeli apology, delivered to Erdogan in 2013 by Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu in a phone call brokered by Barack Obama, the deal begins with a financial compensation: Israel will hand the Turkish Government US$20 million with which the Turks will set up a fund that will pay the raid-victims’ families according to its own criteria.

The Turks, in turn, committed to never request additional compensation, and to pass legislation that will cancel all pending legal suits, and prevent future ones, against any Israelis in the wake of the incident. Once the Turkish parliament ratifies the deal, diplomatic relations will be fully restored.

Legal experts note that the deal’s financial clause is designed so that Israel does not directly pay people it defines as terrorists, nor does it transfer funds in this context to a non-governmental body. Israel thus avoided setting a legal precedent contrary to its foreign policy and national interest.

Lastly, Israel agreed to allow Turkey to build in Gaza a power station, hospital and desalination plant, and also to ship humanitarian goods to Gaza, provided those enter through the Israeli port of Ashdod, where they will be checked by Israel. This allowed Israel to say that Turkey recognised its right to blockade Gaza, and Turkey to say that the blockade no longer exists.

In one of those surprises which often afflict the Middle East, in between the deal’s conclusion and ratification, Turkey was suddenly faced with the coup attempt that failed the night it was launched.

Responding to the unfolding events, Netanyahu said Israel had reason to believe the events in Turkey would not affect the agreement.

That statement was soon seconded by Erdogan’s adviser, Ilnor Cevik, who in an interview with Israel’s Channel 2 TV – tellingly held in front of Erdogan’s presidential palace – said that if anything the coup “should speed up” the rapprochement.

Turkey needs intelligence in its war on Islamist terror, explained Cevik, noting the cooperation over the years in this regard between Jerusalem and Ankara.

The meaning of this statement, which was obviously cleared in advance with Erdogan, is that the massive terror attacks Turkey has come to face in recent months are its most urgent worry – besides of course the coup and its repercussions. That also explains why Turkey has just brought to an end its crisis with Russia, with Erdogan apologising to President Vladimir Putin for last year’s incident where a Russian fighter-jet was downed.

Turkey, like France and Belgium, is now eager to use Israel’s hard-earned counter-terrorism experience, in all of its aspects: the military, the technological and the administrative.

Meanwhile, the two countries’ already sizable commerce is expected to multiply.

Though few expect the restoration of the pre-Islamist era’s defence relationship, and though tourism will take a while to reach past levels due to Turkey’s internal turmoil, Ankara was careful not to harm other aspects of bilateral trade, which even in the bad years that are now ending totaled an annual US$6 billion. Future gas sales will expand this volume considerably, once construction of a pipeline from the Israeli offshore fields to Anatolia is completed.

The reconciliation with Turkey comes, curiously, against the backdrop of yet more successes in Israel’s diplomatic reach.

Egypt’s replacement of Mohamed Morsi with Abdel Fatah el-Sisi has sharply changed Cairo’s relations with Jerusalem. Sisi seems free of complexes about Israel, and has found in Jerusalem a reliable ally, mainly in the realm of intelligence, in his confrontation with the Islamist insurgency in the Sinai Desert.

In July, shortly after the announcement of the agreement with Turkey, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukri formally visited Israel, the first such visit in nine years. Shoukri was hosted by Netanyahu in his residence, where a photographer caught them watching together the European Soccer Championship final between France and Portugal.

The previous week, Netanyahu emerged in Uganda, to mark the 40th anniversary of the raid on the Entebbe Airport, where his brother Yoni was killed while leading the IDF’s hostage-rescue operation outside Kampala.

Arriving with him were the leaders of Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania and Zambia, who joined Netanyahu and his Ugandan host, President Yoweri Museveni, for what was described as an anti-terror summit.

Ten days later, as if for good measure, the West African country of Guinea, which has a Muslim majority and severed its diplomatic ties with Israel in 1967, announced it was restoring ties with the Jewish state.

Guinea’s leaders, it turned out, were moved by Israel’s dispatch two years ago of a mobile infirmary and medical team while the country fought Ebola.

Meanwhile, reports emerged that Israel was mediating in the conflict between Egypt and Ethiopia over the damming of the Upper Nile, and also that unofficial exports to Gulf states last year totalled US$1 billion. Other reports, from Somalia, claimed that Netanyahu secretly met in Tel Aviv with Somali leader Mohamed Sheikh Mahmoud, whose Muslim-majority East African country has no formal ties with Israel.

The common denominator among these countries is that they are threatened by Islamist terror and face a host of economic and social challenges which Israel can help treat. Evidentally, the diplomatic storm-clouds that gathered on Israel’s horizon earlier this decade have dissipated.

Tags: Africa