Australia/Israel Review

Bibi comes up Trumps in Washington

Mar 3, 2017 | Amotz Asa-El

Amotz Asa-El

It was a breath of fresh air. After eight chilly years opposite a distant and sometimes antagonistic Barack Obama, on Feb. 15, Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu was greeted by US President Donald Trump with regal pomp and unconcealed warmth.

The setting, a red carpet on the White House driveway where the two leaders chatted and joked in front of the cameras, was festive enough, as was the presence of their wives. Yet change soon proved more than atmospheric, when it turned out that Trump was effectively calling into question what had been Washington’s central Middle Eastern tenet.

“I’m looking at two states and one state, and I like the one [formula] both parties like,” the President told reporters, and then added, “I can live with either one.”

The two-state solution had thus seemingly been dealt a serious blow, after having been formal US policy for nearly a quarter of a century.

Just what this means in practical terms has yet to unfold, especially considering that Trump’s sharp change of course came coupled with an equally public warning to Netanyahu, “I’d like to see you hold back on settlements for a little bit.”

Apparently, these quips signal a return to a forgotten era in Washington’s Middle Eastern policy, harking back half-a-century.

American policy in the Middle East should be divided into before and after 1967, when Israel preempted three Arab armies’ approaching attack and captured, among other territories, the West Bank.

Until that war, Washington viewed the region as but another Cold War arena, seeking to contain Soviet expansion by cultivating its own regional alliances. There was no ambition in those days to reinvent the region, and Israel was but another Western outpost alongside countries like Iran, Lebanon, Jordan and Morocco.

The Six Day War changed all this, as Washington came to believe in the feasibility of peace, and to actively seek it.

American mediation was successful in the peace agreements of 1979 and 1994 with Egypt and Jordan, and unsuccessful in other initiatives, from the 1969 Rogers Plan for peace with Egypt to John Kerry’s efforts this decade. However, throughout this era the US always had its idea of how peace should be obtained.

Trump’s statement brings this 50-year history into question.

The previous American thinking was based on two assumptions: First, that the Palestinians can be coaxed to accept Israel as a Jewish state and to get down to the business of building a state. And second, that Israeli-Palestinian peace would radiate throughout the region and spark an economic and social revolution across the Arab world.

Trump and his circle reject both premises.

First, they think that Palestinian leaders, even the secularists in the West Bank, not to mention the Islamists who lead Gaza, continue to reject the Jewish people’s nationhood, and therefore also its right to a state in the Jews’ ancestral land. That is part of what Trump alluded to when he said “the Palestinians have to get rid of some of the hate that they are taught from a very young age.”

Secondly, Trump believes that the civil wars in Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya prove that the Middle East is ablaze regardless of Israel, meaning that an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement will by no means pacify the region.

That is why Trump is attentive to Netanyahu’s talk of a regional peace in which Sunni Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states will be harnessed to foster Palestinian flexibility in prospective peace talks with Israel.

This is not to say things down in the field will now change dramatically, least of all overnight.

Hopes in the Israeli far right for unlimited construction in the West Bank were quickly dashed when Netanyahu cited Trump’s warning to him in order to nip in the bud a call to annex the West Bank city of Maale Adumim, which abuts Jerusalem from the east.

Similarly, Trump’s pick for Ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, disappointed some longtime friends on the Israeli right when he told a Senate confirmation panel that he backed the two-state solution. So also did new US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley and Trump spokesperson Sean Spicer.

A similar retreat seems to be at play concerning the American Embassy’s location. Trump has yet to deliver on his earlier vows to move it from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and there is no indication that the preparations required by such a move are underway.

These hints of pragmatism coincide with Trump’s retreats on his Russian and Chinese fronts. Trump has changed his tune concerning the war in Ukraine, now saying Russia should leave Crimea, and he has also mellowed on the One China idea, which he now says he accepts, after having implicitly challenged it by taking a phone call from Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen.

Even so, in the Middle East Trump is indeed steering a new American direction, reflecting a genuine and deep disagreement with his predecessor’s legacy.

The first Middle Eastern difference between Trump and Obama is that Trump is unequivocal about Islamist terrorism. In his view, this is the most potent and urgent scourge facing the international community and what fuels it is an interpretation of Islam. Obama, by contrast, refused to call Islamism the enemy, and preferred to define as his target not the Islamist ideology, but its weapon, the terrorist.

Secondly, what Trump sees in Islamism on the non-state level, he sees in Iran on the state level.

Obama saw in Iran a legitimate diplomatic partner and a viable regional pivot, one whose leaders can be trusted and whose clout can be enlisted in order to foster regional stability. That is how he ended up leading the international agreement concerning Iran’s nuclear program.

Trump fundamentally disagrees with all these assumptions, and in this regard he is on one page with the Republican-led Congress and indeed the entire Republican establishment.

As Trump and his party see things, Iran originated Islamist violence, first when it overthrew the Shah in 1979, then when it held hostage 52 Americans in the US embassy, and then when its agents killed 305 American and French peacekeepers in Beirut in 1983.

This Shi’ite violence, coupled with subsequent attacks worldwide on embassies, diplomats and dissidents, preceded, and soon inspired, Sunni violence as well. That is why, in Trump’s thinking, Iran’s Islamist regime is part of America’s strategic problem, and can therefore not be part of its solution.

This is before even discussing Iran’s current meddling throughout the Middle East, all of which is abominable from Trump’s viewpoint, on two planes:

Militarily, Iran’s effort to obtain a nuclear bomb is seen in the new White House as a massive threat to world peace. And on the international level, Iran’s effort to cast a network of proxies from Teheran to the Mediterranean and Red Sea, through Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen – threatens America’s hegemony in the Arab world.

Trump therefore seems set to transform Washington’s Middle Eastern priorities. These are no longer topped by peace, but by war – the military war on Islamism’s Sunni version, which currently focuses on ISIS, and the diplomatic war on its Shi’ite version, which focuses on Iran.

That is why Trump is hostile to the nuclear deal with Iran, and that is why he can be expected to seek ways to put Teheran on the defensive – first of all diplomatically and economically, as he has already done by introducing new sanctions, and, at a later stage, possibly also militarily.

After this top priority comes the re-stabilising of the Arab world, and the restoration of Washington’s position within it, especially in Egypt, which has signed hefty arms deals with Russia following Obama’s abandonment of President Hosni Mubarak in 2011.

These are all crucial from Trump’s viewpoint not only because of their direct impact on the US, but because they feed the waves of migration that destabilise Europe.

The Arab-Israeli conflict will only come after all these. And this is besides the fact that the Middle East as a whole places much lower on Trump’s agenda than issues like Mexican immigration, Chinese trade practices, and American taxes, infrastructure and jobs. Barring a sudden external shock, these issues will likely dominate this term’s first half at least. Until then, Mideast peace will have to wait.

What will not wait is Trump’s impatience with the United Nations’ treatment of the Middle East in general, and Israel in particular.

“The UN Department of Political Affairs has an entire division devoted to Palestinian affairs,” said US Ambassador Nikki Haley in a press conference at the UN. “Imagine that,” she went on, “there is no division devoted to illegal missile launches from North Korea. There is no division devoted to the world’s number one state-sponsor of terror, Iran. The prejudiced approach to Israeli-Palestinian issues does the peace process no favours. And it bears no relationship to the reality of the world around us. The double standards are breathtaking.”

David Ben-Gurion, Binyamin Netanyahu, or Abba Eban couldn’t have said it better.

Tags: Israel

RELATED ARTICLES

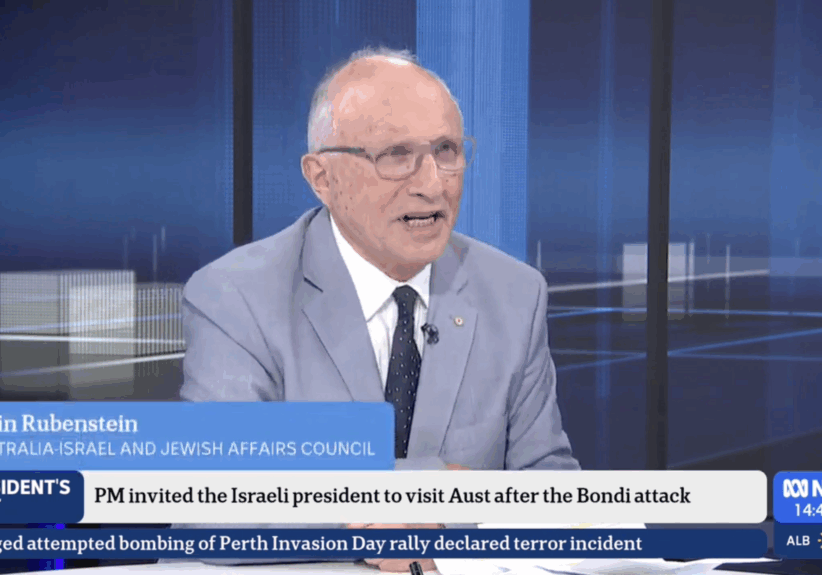

Herzog visit comes at a profoundly significant moment for the Jewish community: Arsen Ostrovsky on BBC radio