Australia/Israel Review

Books: Beirut Bob

Mar 1, 2006 | External author

By Efraim Karsh

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East

by Robert Fisk (Knopf, 1107 pp, US$40.00)

No foreign journalist is more closely identified with the Middle East than the British writer Robert Fisk. Through 30 years of reporting from his base in Beirut, first for the London Times and now for the Independent, Fisk has built a reputation not only as an intrepid war correspondent but as a foremost commentator on the volatile region. His eye for sensational detail and his readiness to cover the hottest flashpoints have won him worldwide publicity and numerous professional awards.

No foreign journalist is more closely identified with the Middle East than the British writer Robert Fisk. Through 30 years of reporting from his base in Beirut, first for the London Times and now for the Independent, Fisk has built a reputation not only as an intrepid war correspondent but as a foremost commentator on the volatile region. His eye for sensational detail and his readiness to cover the hottest flashpoints have won him worldwide publicity and numerous professional awards.

None of this has made Fisk notably modest, as the thousand-page heft of his latest book suggests. The ostensible subject of The Great War for Civilisation is the turbulent period during which Fisk has been stationed in the Middle East, from the Iranian revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the late 1970s to the two US-led wars in Iraq and, above all, the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict. But the grand unifying theme is Fisk himself. As he writes in his preface, reminiscing about his initial posting with the Times in 1976: “I was twenty-nine, and I was being offered the Middle East. I wondered how King Faisal felt when he was ‘offered’ Iraq or how his brother Abdullah reacted to Winston Churchill’s ‘offer’ of Transjordan.”

That Fisk would so readily identify himself with the region’s Arab autocrats is no accident. It is an apt if inadvertent metaphor.

The role of journalists, Fisk writes in his opening pages, is to be “the first impartial witnesses to history.” “If we have any reason for our existence, the least must be our ability to report history as it happens so that no one can say: ‘We didn’t know – no one told us.’”

For Fisk, this burden of “impartiality” has led in a distinctive direction. His book, like his journalism, draws on the broad historical narrative that has now become standard in Western universities. In this view, culpability for the Middle East’s endemic malaise rests squarely on the West itself, beginning with the European powers that, after World War I, carved from the remains of the Ottoman empire a series of makeshift states. As Fisk puts it:

[I]t was to take my father’s generation just 23 months to create these artificial borders … We victors promised independence to the Arabs and support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Promises are meant to be kept. And so those promises…were betrayed, and the millions of Arabs and Jews of the Middle East are now condemned to live with the results.

Having been duped by the Europeans into a revolt against their Ottoman suzerain, Arab nationalists, in Fisk’s telling, could never accept the distorted political order that arose in the aftermath of the Great War.

Still less could they accept its most dire eventual consequence: the establishment in 1948 of the state of Israel. As Fisk writes, “Why did the Palestinians have to bear the fate of Britain’s World War I promise to a people whose ancestors lived on their land two thousand years before?” As for the defeat of the Palestinian and Arab attempt to destroy the Jewish state at its birth, that, Fisk argues, was little more than a reverse exercise in ethnic cleansing, at the Arabs’ expense.

The passage of time has only magnified this injustice, the story of which occupies a lion’s share of the pages and constitutes the true emotional core of The Great War for Civilisation. The Palestinians, as Fisk tells it, now suffer not only from the Jews but from a mercenary indigenous leadership willing to sign away their historic claims. Typical of his reporting in this regard is his account of the Palestinian response to the “Declaration of Principles” (DOP) that marked the formal beginning of the Oslo negotiations in 1993. As dignitaries congregated on the White House lawn for the historic signing ceremony, Fisk travelled to the West Bank, where he found that “No one…spoke in favour of Arafat’s acceptance of an ‘interim’ solution.’”

When it comes to the Israelis themselves, Fisk finds it difficult to catalogue the full range of their purported crimes – but he tries. One episode dwelled upon in painstaking detail is the 1994 murder of 29 Palestinians in Hebron by the Jewish zealot Baruch Goldstein.

Nor can Fisk resist rehearsing the particulars of another favourite episode of supposed Israeli perfidy, the Israel Defence Forces’ anti-terror campaign in the towns and refugee camps of the West Bank in April 2002, at the height of the second intifada. Dedicating four full pages to events in Jenin, where 38 Palestinian combatants and 14 civilians were killed during heavy fighting (fighting that also took the lives of 23 Israeli soldiers), Fisk struggles to find the correct terms for the alleged horrors: “How big does a massacre have to be before it qualifies as a genocide? How many dead before a genocide becomes a holocaust?”

|

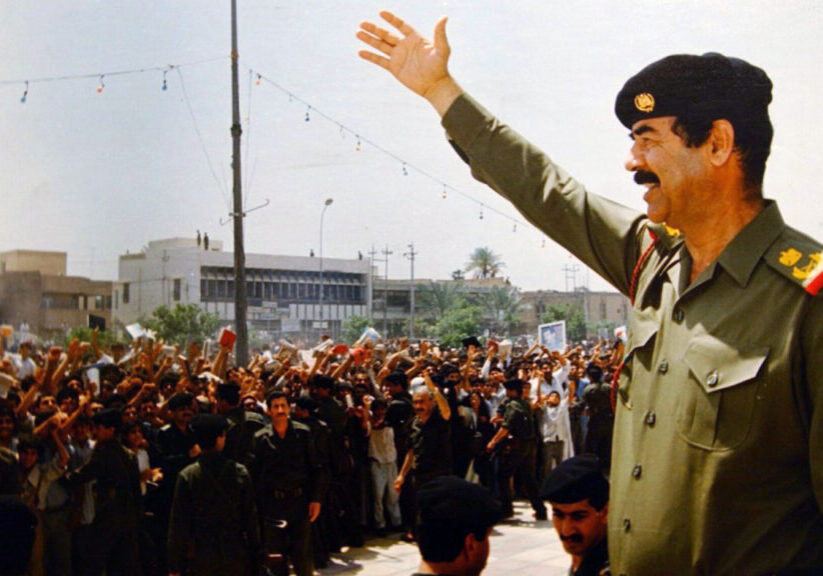

| Fisk: intellectual pretence |

At every turn, according to Fisk, and whether it is the Palestinians or other Arab and Muslim populations at issue, the West applies to the Middle East a gross double standard. The word “terrorism”, he writes, “has become a plague on our vocabulary.” It is “the excuse and reason and moral permit for state-sponsored violence – our violence – which is now used on the innocent of the Middle East ever more outrageously and promiscuously.”

Fisk’s indictment is a familiar one, at least for anyone who has attended to Arab propaganda over the years or, more recently, to the sloganeering of the anti-Israel Left. But he does not wish to be seen as just another partisan in the debate. Fisk wants to be taken seriously, both as a journalist and as a writer with wider intellectual and historiographical ambitions. In this, he falls dismally – if predictably – short.

First there is the problem of simple accuracy. It is difficult to turn a page of The Great War for Civilisation without encountering some basic error. Jesus was born in Bethlehem, not, as Fisk has it, in Jerusalem. The Caliph Ali, the Prophet Mohammed’s cousin and son-in-law, was murdered in the year 661, not in the 8th century. Emir Abdallah became king of Transjordan in 1946, not 1921. The Iraqi monarchy was overthrown in 1958, not 1962; Hajj Amin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem, was appointed by the British authorities, not elected; Ayatollah Khomeini transferred his exile from Turkey to the holy Shiite city of Najaf not during Saddam Hussein’s rule but fourteen years before Saddam seized power. Security Council resolution 242 was passed in November 1967, not 1968; Anwar Sadat of Egypt signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1979, not 1977, and was assassinated in October 1981, not 1979. Yitzhak Rabin was Minister of Defence, not prime minister, during the first Palestinian intifada, and al-Qaeda was established not in 1998 but a decade earlier. And so on and so forth.

The deeper problem with Fisk’s work is not the sort of thing that can be fixed by acquiring a better research assistant or fact-checking apparatus. Facts must be placed in their proper context, after all, and this demands a degree of good faith that Fisk utterly lacks. Indeed, so blatant and thoroughgoing are his ideological prejudices that his very name has entered the lexicon of the internet as a synonym for systematic bias.

The precise angle of his tilt has been confirmed by Osama bin Laden himself, who, in a videotaped message on the eve of the 2004 presidential election in the US, commended Fisk by name for his incisive and “neutral” reporting. On Planet Fisk, there are bad guys and there are victims, and the victims – the Arabs – can do no wrong, at least none for which they are ultimately responsible.

As for the long record of Palestinian terrorism, Fisk has his own bag of “weasel phrases” to avoid calling it by its proper name. He describes as mere “deaths” the cold-blooded murder of eleven Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics, as if they died of physical over-exertion. The massacre of 26 passengers at Tel Aviv airport that same year comes into view as “a Palestinian-inspired shooting.”

Such is the general standard Fisk applies as an “impartial witness to history.” Massacres of innocent civilians by Arab and Islamic militants throughout the world – from Jerusalem and Tel Aviv to Manhattan, Bali, and Baghdad – are for him not acts of terrorism but rather the understandable and altogether patriotic response of people brutalised by colonial occupation. The curious effect of this effort to absolve Middle Easterners of any blame or responsibility for their region’s problems, or their own deeds, is to make Fisk guilty of the sin for which he endlessly berates the West; he patronises his subjects in the worst tradition of the “white man’s burden”.

Though Fisk compares himself to Arab kings at the start of his book, he emerges, ultimately, much more like Lawrence of Arabia, who concluded that the Arabs were “a limited, narrow-minded people”, incapable of decent behaviour because their “inert intellect lay fallow in incurious resignation.” As the eminent Orientalist Bernard Lewis likes to joke, possessing such fundamentally racist attitudes is what it means today to be “pro-Arab”.

![]()

Professor Efraim Karsh is head of Mediterranean Studies at King’s College, University of London. Prof. Karsh’s latest book, Islamic Imperialism: A History will be published by Yale University Press in April. © Commentary, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iraq