Australia/Israel Review

Trump, the JCPOA and the NPT

Jun 1, 2018 | Ran Porat

On May 8, US President Donald Trump announced his decision to withdraw the US from the 2015 nuclear agreement between Iran and the West – aka the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). This step meant the start of a 180-day timeline for the renewal of a number of painful US sanctions on Iran, as well as the reimposition of penalties on non-American companies and international financial institutions for various commercial activities with Iran.

There are many ways to assess the significance of this decision. It is yet another chapter in the multifaceted and very volatile historical relationship between Iran, its region and external great powers since the First World War. Abandoning the agreement is already having a ripple effect on the world economy and is adding another layer of complexity to the political tension between the modern great powers competing in the region – the US, Russia and China.

Yet one important aspect of President Trump’s announcement is that it reinforces the validity of existing arms control regimes. To fully understand this claim, it is important to examine the pillars of arms control and juxtapose the logic that dominates nuclear arms control with the raison d’etre of the JCPOA.

The NPT regime

As in many other fields of academic scholarship, there is more than one definition of arms control.

In general, arms control largely deals with actions of states and governments, their policies and the arrangements they enter into, and the strategic calculation of policymakers about the costs and benefits of both arms in their own possession and in the possession of their allies and adversaries.

Arms control is not restricted to the limitation or dismantling of weapons already possessed. It is also about counter-proliferation – coordinated effort to prevent the spread of dangerous weapons, and especially weapons technology, into the hands of other actors. The most important form of international counter-proliferation arrangements is the nuclear arms control regime.

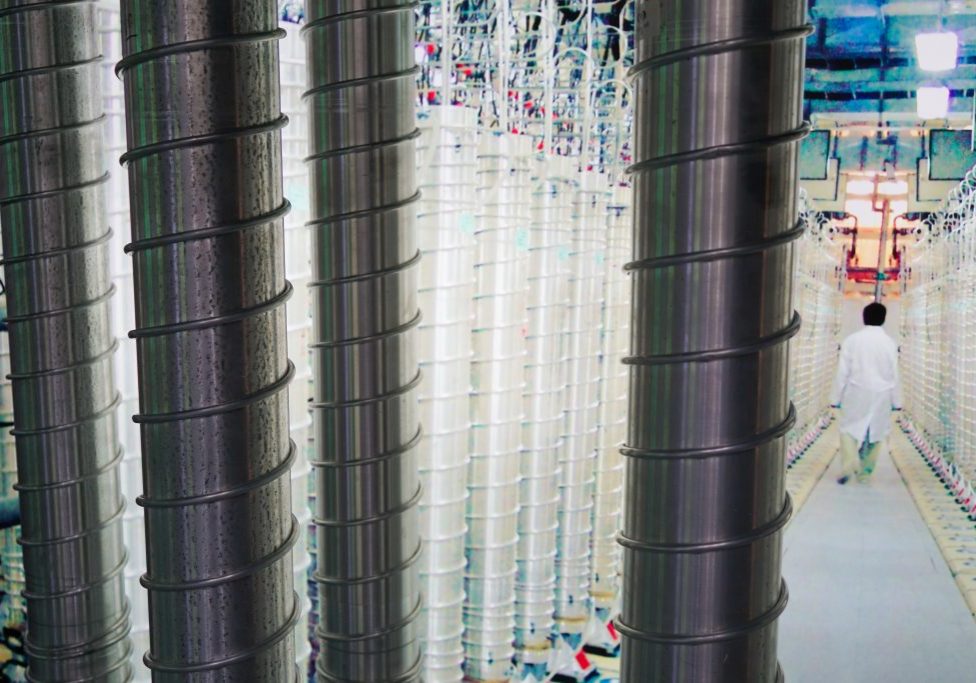

At the heart of the nuclear arms control regime is the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). This 1968 international treaty is an agreement based on a trade-off between the countries that were in possession of atomic weapons at the time (US, UK, USSR-Russia, France and China) and the rest of the world. The deal is simple: the super-powers would aid the spread of nuclear technology for peaceful purposes (to generate electricity or for medical uses etc.), in return for unequivocal commitment by all other states not to acquire atomic weapons. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was given a referee role, making sure signatory states to the NPT are complying with their obligations not to divert nuclear facilities and material for military uses.

The NPT and the JCPOA

Iran has signed and ratified the NPT – yet the IAEA has found it to be in breach of the NPT on numerous occasions since 2003. Those breaches were reported to the UN Security Council (UNSC), the international governing body with authority to “punish” states for not adhering to international law or for threatening global security. Eventually, the UNSC put in place severe and extensive sanctions on Iran to mark a clear line in the sand – breaching key arms control accords and threatening world security is unacceptable and would lead to grave consequences.

The JCPOA, negotiated with Iran by the Obama Administration together with the UK, France, Germany, Russia and China, turns the basic arms control reasoning reflected in the NPT on its head.

A country secretly developing nuclear arms, in direct contradiction to its international commitment as a signatory to the NPT, was given the right to continue developing an allegedly civilian nuclear industry, monitored, yet with only minimal and relatively short-lived limitations. In other words, the agreement meant that Iran had retained the right awarded by the NPT to use peaceful nuclear energy, and at the same time, it was exempt from paying any significant price for unequivocally side-tracking nuclear activity into a military project and lying to the IAEA about it.

In direct contrast to the logic of the NPT, instead of penalties, the deal showered Iran with rewards for its proliferation campaign, only partially disclosed, after it had illegally purchased crucial military elements from North Korea and from Pakistani scientist AQ Khan. The final oddity in the alternate arms control universe that is the JCPOA is the gradual relief of the ‘punishment’ limitations on its nuclear development – giving Iran a free ride to push on with as large a nuclear project as it desires providing it ostensibly claims it to be peaceful – after a few years (the so-called “sunset clauses”).

The logic of the JCPOA

A popular defence of the JCPOA is that it is not realistic to expect Iran to completely let go of its nuclear capabilities, and any limitations and monitoring on Iran’s nuclear activities are better than none at all. JCPOA advocates say that they have adopted the premise articulated by US President Ronald Reagan; a “trust but verify” policy. Hence an ostensibly intensive, yet actually incomplete, inspection mechanism was put in place on Iran’s known nuclear-related activities and sites.

Unfortunately, the inspection regime agreed to by the Obama Administration and European officials has gaping holes. Most notably, key segments of Iran’s atomic weapons development program were not part of the JCPOA deal and remained unlimited and unmonitored. In addition to the effective prohibition on inspections of Iran’s self-declared military sites, the most important blind spot in this respect is Iran’s ongoing work on the key platform for launching atomic warheads, its long-range missile development efforts.

Above all, Western JCPOA negotiators purposefully avoided pressuring Iran to agree to full nuclear disarmament. They could have followed the past precedents of complete denuclearisation that was the precondition for negotiations with Libya under Muammar Gaddafi and with South Africa, when those countries agreed to bring their illegal nuclear programs under NPT compliance.

In both cases, before they could be readmitted to the family of nations, the governments in question had to come clean about their past efforts to acquire atomic weapons, to eschew all future nuclear enrichment and allow all related equipment and sites to be dismantled or changed into monitored civilian facilities. From an arms control perspective, this steadfast demand to denuclearise was a success. Most declared components of the infrastructure related to the military nuclear programs were dismantled and removed from the country. Remaining elements were put under strict limitations and monitoring. Key documents were studied by inspectors and then destroyed so no instructions and plans were left to enable the resumption of such activities.

Israel’s revelation of a secret and apparently deliberately concealed Iranian nuclear archive, as announced by Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu on April 30, proves that Iran was never going to fully expose its atomic weapons project. Worse, it shows Teheran never intended to fully halt its ongoing efforts, which are still active, to acquire nuclear bombs and the means to deliver them – only to temporarily delay some elements of this effort. Reports from across the world regularly point to illegal Iranian attempts to buy equipment or technology for its nuclear program. Teheran has breached its NPT obligations, and continues to do so now, yet the logic of the NPT, which says a state that has done this should fully denuclearise, is being overturned in Iran’s case.

Duties over privileges

Trump’s decision to pull the US out of the JCPOA arguably returns full circle to the original logic of the NPT. This is because it has dramatically raised the consequences of the Iranian non-compliance with the arms control regime – rather than settling for the “any limitations are better than nothing” logic of the JCPOA. The US move also reinvigorates the policing power of the international nuclear regime by insisting the role of the international community is not only to monitor whether a state is in breach of its international obligations, but also to see that it pays a significant price for that behaviour.

The JCPOA deal was weighted toward the “privileges” side of the NPT equation, emphasising Iran’s ostensible “right” to benefit from peaceful nuclear energy. Now, the Trump Administration has arguably realigned the relationship with Iran so that a record of clear adherence to the duties and responsibilities attached to the NPT is a firm precondition for accessing any such “right”.

Furthermore, the JCPOA deliberately avoided tackling Teheran’s continuing proliferation campaign and its threat to the Middle East at large with its terrorist engagement in Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Gaza.

This is why US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, in his speech of May 21, described the JCPOA as a bad bet for world security and stability. To rectify the damage inflicted by the JCPOA, the US is now demanding that any future arrangement with Iran also address the missile program and its destabilising regional activities.

With the end of the bipolar cold war alignment, nuclear non-proliferation in the 21st century means facing the challenge of both non-state elements, such as terrorist organisations, and rogue states, who actively defy international norms.

Countering the first type of actor, terror groups, requires intensely safeguarding nuclear facilities and material stockpiles. Confronting the second kind, countries with malicious and dangerous aspirations, calls for raising the price for defiance of the pillars of global order.

“We will… ensure Iran has no path to a nuclear weapon – not now, not ever,” promised Pompeo – an essential demand, consistent with past precedents, that requires a proven abuser of the NPT, like Iran, to agree to full denuclearisation as the “price” of readmittance to the regime.

Scrapping the JCPOA is in line with this strategy and, if implemented wisely and consistently, could be a step towards a safer world in the long term.

Dr. Ran Porat is a researcher at the Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation at Monash University.

Tags: International Security