Australia/Israel Review

Ship Outed

Nov 24, 2009 | Jeffrey White

What the Francop tells us about Iran and Hezbollah

By Jeffrey White

On November 3, 2009, Israeli naval forces intercepted an Antigua-flagged cargo ship approximately 160 km off Israel’s coast. The ship, the Francop, was brought to the port of Ashdod and searched, leading to the discovery of some 500 tons of weapons reportedly from Iran. Israeli officials believe the cargo was bound for Hezbollah via Syria. While Iran has been sending arms to Hezbollah through Syria for years, this case has important military and political implications.

Iranian arms supplies underwrite Hezbollah’s political position in Lebanon, increase the risk for a conflict with Israel, and ensure that any such conflict will be more intense and lengthier than if Hezbollah lacked such support. This most recent affair also shows Iran’s willingness to risk embarrassing exposure in its support for Hezbollah, even as it engages in sensitive negotiations with the international community over its nuclear program. This underlines the strategic nature of the Iran-Hezbollah relationship and the importance Iran attaches to Hezbollah as a component of its own deterrent arm.

The Francop’s Cargo

The Francop was seized after being stopped, boarded, and searched by Israeli naval commandos supported by surface naval units. The preliminary search revealed arms hidden in commercial cargo containers. According to the shipping documents, the cargo was originally loaded in Bandar Abbas, Iran, brought by another ship to the Egyptian port of Damietta, and then transloaded to the Francop, with an ultimate destination of Latakia, Syria. This destination was confirmed by Syria’s foreign minister, although he denied that the shipment included arms. Neither the ship’s crew nor the Egyptian authorities apparently had any knowledge of the cargo’s nature.

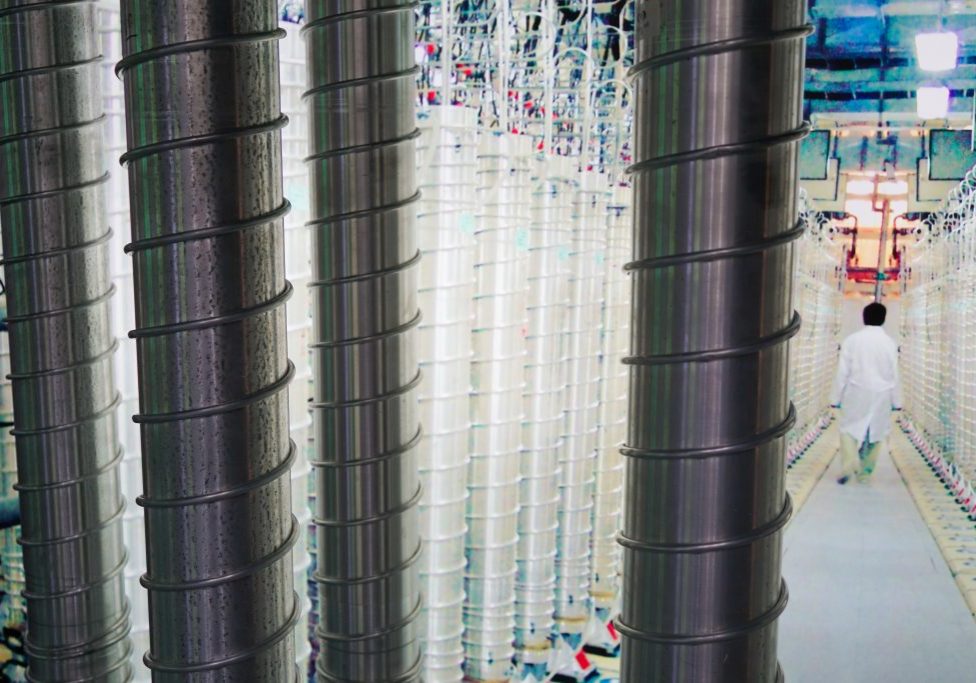

Following the preliminary search, the Israelis escorted the Francop to the port of Ashdod, where a complete search revealed the full extent of the arms shipment. Labels on the shipping containers and shipping documents, as well as markings on ammunition crates and the ammunition itself, established a clear link to various Iranian government organisations, including the Iranian state shipping line and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

This was a large and important shipment involving up to 500 tons of weapons stored in 36 containers. Reports and video from the Israeli military have indicated the presence of the following weapons:

- 2800 artillery rockets (122 and 107 mm)

- 9000 mortar shells (60, 81, and 120 mm)

- 20,000 fragmentation grenades

- 600,000 7.62-mm rounds for infantry weapons

- 3000 106-mm rounds (for recoilless rifles)

Not found, or at least not reported, were larger and longer-range types of artillery rockets, such as the Fajr-3 and Fajr-5, and advanced types of antitank missiles, such as the AT-5 and AT-14. Apparently, no munitions types that would result in a significant upgrade of Hezbollah’s military capability, such as surface-to-surface or surface-to-air missiles, were discovered.

Significance of the Interception

The Francop incident is significant at the tactical-operational, strategic, and political levels. At the tactical-operational level, it gives insight into the asymmetric conflict that persists between Hezbollah – backed by Iran and Syria – and Israel. Both Iran and Syria seek to increase Hezbollah’s capability to wage sustained warfare against Israel.

Since the 2006 war, Hezbollah has reportedly increased its artillery rocket inventory to as many as 40,000, including substantial numbers of longer-range types. An inventory this large would potentially allow Hezbollah to direct heavy fire at Israel for many months. Theoretically, the group could launch 200 rockets per day for 200 days, an output that would far exceed in number and duration what it achieved in 2006, when some 4000 rockets of various types were launched against Israel in 34 days. The large number of 107-mm rockets in the shipment (about 2000) suggests that Hezbollah intends to operate deep into southern Lebanon – that is, inside the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon, or UNIFIL, zone. These rockets have a relatively short range of 8 kilometres, and their deployment anywhere other than close to the Israeli border would not make sense.

Iran and Syria are also providing weapons and munitions that support Hezbollah’s ability to conduct ground operations against the IDF. In 2006, Hezbollah was able to conduct a skillful and determined defence of southern Lebanon by employing light infantry equipped with sophisticated antitank weapons. The group intends to build on this model for any future conflict with Israel. Mortars, which are mobile and accurate weapons, are a good fit, and the larger types can also be used offensively. Overall, the scale of the Hezbollah buildup suggests that it intends to wage any future conflict more broadly and more intensively than in the past.

At the strategic level, increasing Hezbollah’s capability serves Iranian and Syrian interests directly. A powerful Hezbollah rocket force constitutes part of Iran’s deterrence program in the face of a potential Israeli strike on Iranian nuclear facilities. Should Israel take such a step against Iran, it would have to be prepared to deal with attacks from Lebanon. This reality would complicate military planning and potentially consume command attention, along with planning, operational, and intelligence assets. Similarly, enhanced Hezbollah capabilities play into the Israeli-Syrian military equation, both by increasing the potential threat to northern Israel and by stiffening the defence against a potential approach by Israeli ground forces to Syria through Lebanon.

On another level, the Hezbollah buildup puts pressure on the deterrence measures established by Israel in the north since the 2006 war. With growing offensive and defensive capabilities, Hezbollah adds to the risk that Israeli deterrence will fail through accident, miscalculation, or an intentional military exchange. The inherent uncertainty of deterrence becomes even less sure with the rapid enhancement of military capabilities.

Finally, greater military capabilities strengthen Hezbollah’s political position in Lebanon. As the country’s only political party with substantial military might, exceeding that of the Lebanese Army itself, Hezbollah enjoys a distinct advantage in national politics. The effect is that the group is emboldened domestically, bolstered in its claim to be a “resistance” movement and less willing to act as a normal political party. Hezbollah does not need rockets for use in the internal Lebanese struggle, but an enhanced infantry capability gives useful backing to the group’s rhetoric.

The seizure of the Francop and its weapons cargo must be seen in the context of the ongoing Israeli confrontation with Iran and Syria. It is one event in what has become a regional struggle involving proxy forces (Hezbollah and Hamas), intelligence operations, and long-range military strikes. The Francop incident offers only a glimpse into a regular pattern of activity, with arms reaching Hezbollah along multiple paths.

Israel has some capability to identify, track, and stop arms carriers at sea, and has had some success in doing so. The Francop case is not the first in which a cargo ship has been boarded by naval commandos and taken to an Israeli port, and unconfirmed reports indicate that Israel is actively interdicting Iranian arms shipments, sometimes through the use of direct military force, in the Red Sea area. Even if Israel can impede the maritime flow of arms, no effective way exists, short of war, to stop arms shipments to Hezbollah directly from Syrian arms depots or by air from Iran to Damascus and then into Lebanon.

The Francop incident illuminates weaknesses in the international effort to prevent arms from reaching Hezbollah, as embodied in UN Security Council Resolutions 1701 and 1747, and in UNIFIL and NATO naval operations. Iranian compliance remains a major problem: more could be done to examine cargo originating in Iran, to raise the cost (both reputational and financial) to port authorities and shipping companies that do not exercise vigilance regarding Iranian smuggling practices, and to increase the focus on ships and cargos bound for Syrian ports. Such measures are essential – even if they do not eliminate the problem. Hezbollah’s military buildup will likely continue largely unabated, however, with all this implies for stability in the region.

Jeffrey White is a defence fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, specialising in the military and security affairs of Iraq and the Levant. © Washington Institute, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: International Security