Australia/Israel Review

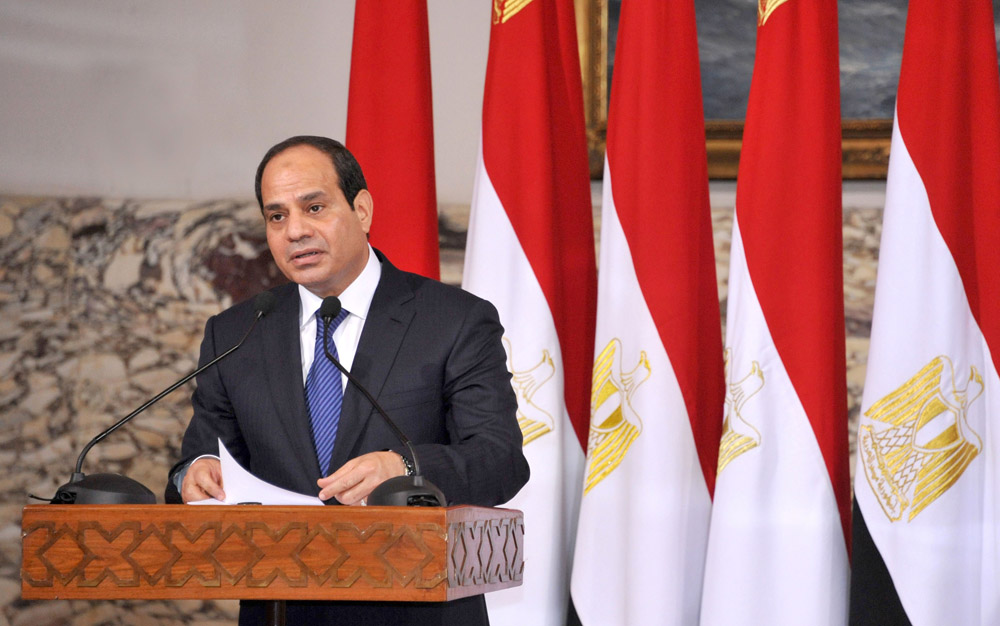

Israel and Egypt in the age of al-Sisi

Aug 27, 2015 | Amotz Asa-El

Amotz Asa-El

Four years after pan-Arab upheaval shook its political foundations, Egypt is treading new economic, political, and diplomatic paths while increasingly harmonising with the Jewish state next door.

The 2011 fall of Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year autocracy was followed by three successors within less than three years, yet the regime that emerged from that mayhem is today entering its third year seemingly increasingly comfortable at the helm.

Led by President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, 61, the government is a product of economically-fuelled unrest that was exploited by the Muslim Brotherhood before being quelled by the military. Sisi, the American-trained former commander of the armed forces, understood from the outset that to be successful he had better focus on the economy – unlike the Islamist Mohamed Morsi whom Sisi unseated in July 2013 while serving as his defence minister, and unlike Mubarak, whom Sisi served as chief of intelligence.

Sisi therefore set out to deliver on three fronts: spending, housing, and infrastructure. Displaying the fiscal resolve his predecessors lacked, he slashed gasoline subsidies, hiking the price overnight by 80%, as part of a broader retreat from subsidies that were designed to buy social quiet at the cost of a quarter of the budget.

Surprisingly, the move – one which economists had prescribed for years, but politicians had feared would trigger riots – passed with relative calm.

Before that, Sisi struck a US$40 billion deal with Dubai-based Arabtec to build thousands of affordable-housing units in 13 sites stretching from Luxor in the south to Alexandria on the Mediterranean. Intended to create a million jobs and house many of Egypt’s restless young adults, this scheme may or may not meet its 2020 deadline, yet its very launch, even before Sisi formally became president in June 2014, meant he realised his political fate would depend on delivering on the economic front.

Then, as if to offset the housing project’s distant deadline, Sisi announced an ambitious project to expand the Suez Canal within twelve months. This summer the new canal was opened, ahead of schedule. The original164-km Suez Canal, dug in the nineteenth century over ten years, is now paralleled by a second 35-km lane which allows two-way traffic between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, doubling daily traffic limits from 49 to 97 ships.

Revenues are expected to soar, from an annual US$5 billion to more than US$12 billion. Industrial projects that will be built along the new canal are expected to generate a million jobs. The project has its opponents, who argue that the US$8.2 billion it cost could have been better spent, but they too agree that the new canal is a remarkable administrative feat and an unambiguous statement of political intent.

In early August, cruising through the inaugurated waterway in full military regalia under an air force flyover, while standing regally in the yacht that was the first to cross the original canal, in the presence of world leaders – Sisi sent his people a message that echoed loud and clear: Egypt has a leader, and he means business.

Sisi’s self-confidence and sense of purpose come across equally forcefully in his diplomacy. Faced with American reprimands concerning his harsh treatment of fundamentalist opponents, Sisi stunned Washington by embarking on a strategic waltz with Russia.

Cairo had been deep in Washington’s diplomatic orbit and loomed prominently in its list of military clients. For four decades, Cairo received an annual US$1.3 billion in aid from Washington while anchoring American interests in the Arab world and Africa.

Now, what began with Anwar Sadat’s defection from East to West in the early 1970s, came to its end when Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu emerged in Cairo in November 2013 for a high-profile visit that was followed by a US$3.5 billion arms deal.

The honeymoon with Moscow was clearly strategic. Crowned by Sisi’s visit to Moscow in early 2014 and by President Vladimir Putin’s arrival in Cairo last February, it does not undo Cairo’s relationship with the US, but it effectively tells Washington to think twice in the future before telling Egypt how to manage its affairs.

Driven by the Egyptian military’s alarm over Barack Obama’s abandonment of Hosni Mubarak in 2011, and by the Egyptian intelligentsia’s discomfort with Obama’s Cairo speech in 2009 that many there found patronising, Sisi’s superpower diplomacy continues a historic pattern: In the 1950s, Gamal Abdel Nasser responded to the domineering attitude of the Anglo-French by inviting the Soviet Union to build the Aswan Dam; and in the 1970s Anwar Sadat responded to the patronising Soviet approach to relations by reverting to Washington’s side. Now, Abdel Fatah Sisi has responded to American admonitions by giving Russia an unexpected bonanza.

Washington understood the message, reaffirming its aid to Egypt and abandoning previous attempts to leverage that aid to seek political reforms.

Sisi showed similar resolve in his attitude toward Turkey. Following then-prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s insistence that the newly-deposed Mohamed Morsi remained Egypt’s legal leader, Sisi expelled the Turkish ambassador and recalled the Egyptian ambassador from Ankara. Relations between the two Middle Eastern powers remain tense today – Egypt sees Turkey’s backing of Egypt’s Islamists as attempted subversion of Cairo’s internal affairs.

While snubbing Turkey and sidelining the US, Sisi has cultivated Saudi Arabia as Egypt’s regional anchor. Having obtained last March a US$12.5 billion aid package from Saudi Arabia and its Gulf neighbours, Sisi has harnessed them to his economic reform endeavours, most notably by financing the affordable-housing project.

Riyadh and Cairo are in broad agreement about the upheaval that has unsettled the Arab world since late 2010. Then again, in contrast to the assertiveness he displayed in his dealings with the global powers, in the Middle East, Sisi has so far preferred to focus primarily on his own country, leaving regional causes to Saudi Arabia’s leadership.

Like the Saudis, Sisi blames the Syrian civil war on Bashar Assad and his sponsors in Teheran. However, in line with his focus on Egypt and its economy, and in contrast to Hosni Mubarak’s style, he has shunned playing the role of regional leader on the issue.

Sisi has sent planes to bomb ISIS targets in Libya to his west, and warships to help fight the Shi’ite insurgency in Yemen to his south, but he has not joined the attacks on Islamic State to his north. Of course, this policy is the result not only of a choice to focus on Egypt and its economy, but also of the constraint that Sisi’s Egypt is up to its neck in its own Islamist insurgency.

Since overthrowing the Islamists, Sisi’s armed forces have lost at least 600 troops and policemen in the Sinai in scores of guerrilla attacks by multiple Islamist organisations – all of which have sunk roots there since Mubarak’s downfall in 2011.

In July, a particularly fatal and well-planned attack took the lives of 17 Egyptian troops when six different military and police outposts were attacked simultaneously near Sheikh Zuweid, southwest of Gaza. ISIS fighters deployed shoulder-fired missiles, car bombs and suicide attacks. Subsequent fighting claimed the lives of 100 Islamists, according to the Egyptians.

Though more dramatic and sophisticated than most, it was but one of countless daily incidents in the peninsula, mainly in its northern parts, involving both Islamists who come from outside, and indigenous Bedouin nomads who have been feeling disenfranchised by mainland Egypt for years.

Aware of this, Sisi says he will connect the Sinai and the mainland with six Afro-Asian tunnels under the Suez Canal. Having seen the swiftness with which he expanded the canal, people now realise that if Sisi says he will build something chances are good it will be built. How this will impact the insurgency is another question.

Actually a devout Muslim, Sisi sees in the Muslim Brotherhood’s hostility to modernity a strategic threat to his country’s future. His war on the fundamentalists has therefore been relentless and brutal.

Most memorably, in the weeks after the Islamists’ overthrow, more than 600 demonstrators were killed by troops who raided two sit-in camps in central Cairo after the Islamists rejected his demands to clear the area peacefully.

Thousands of Islamists have been arrested over the past two years and received long jail sentences. More than a hundred were handed death sentences, including former president Morsi, who was convicted of breaking out of prison in 2011 after allegedly plotting with Gaza-based Hamas to destabilise Egypt.

Egypt, then, is in some ways where Chile was after Augusto Pinochet overthrew Salvador Allende, brutalised the opposition, and invigorated the economy while restoring order to a country that had been sliding into chaos.

From Israel’s viewpoint, it is a situation that demands great diplomatic caution but also offers some unexpected opportunities.

Sisi invited practically the entire world to join in the celebrations of the inauguration of his new canal, excepting only four countries: Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Israel. Inviting Israel would have been too much of a risk for him, while his war on the Islamists rages.

However, Sisi has appointed a new ambassador, Hazem Khairat, who is now on his way to Tel Aviv three years after Morsi recalled the previous ambassador in response to the fighting at the time in Gaza. More substantively, cooperation between the Israeli and Egyptian militaries and intelligence agencies is close, constant, and systematic.

Cairo and Jerusalem realise they share enemies, interests and aims. Both want to see the Sinai cleared of its Islamist infiltrators; the Arab world offering its masses more opportunity and prosperity; and Iran pushed back from the many regional fronts on which it is meddling.

Egypt is smiling on Jerusalem in assorted ways, from warming up to Israeli Ambassador Haim Koren and inviting Foreign Ministry Director-General Dore Gold to visit Cairo for special consultations, to phone conversations between Sisi and Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, and to the broadcasting on state TV, during the prime viewing time over Ramadan, of a soap opera about a love affair between an Egyptian Muslim and Jewess that depicts the Jews humanely.

Meanwhile, Israeli energy tycoon Yitzhak Tshuva last March signed a deal with Egyptian company Dolphinus to supply gas to Egypt from Israel’s large offshore Leviathan field.

All this is happening while Egypt, regardless of what Israel says or does, accuses Gaza’s Hamas government of feeding the anti-Egyptian insurgency in the Sinai.

Just where all this leads is anyone’s guess. What can be said for now is that the more Sisi consolidates his power, and the more he improves the life of the average Egyptian, the more relations between Cairo and Jerusalem will expand and the deeper they will run.

But even today, with Turkish President Erdogan having destroyed his country’s previous role as Israel’s key regional ally, it is clear that Sisi’s Egypt has taken its place.

This article is featured in this month’s Australia/Israel Review, which can be downloaded as a free App: see here for more details.

Tags: Egypt