Australia/Israel Review

Asia Watch: Restore from backup?

Oct 27, 2022 | Michael Shannon

Malaysia will soon have the chance to reset its protracted governmental instability through national elections, but the afflicted body politic appears well beyond the scope of any vote.

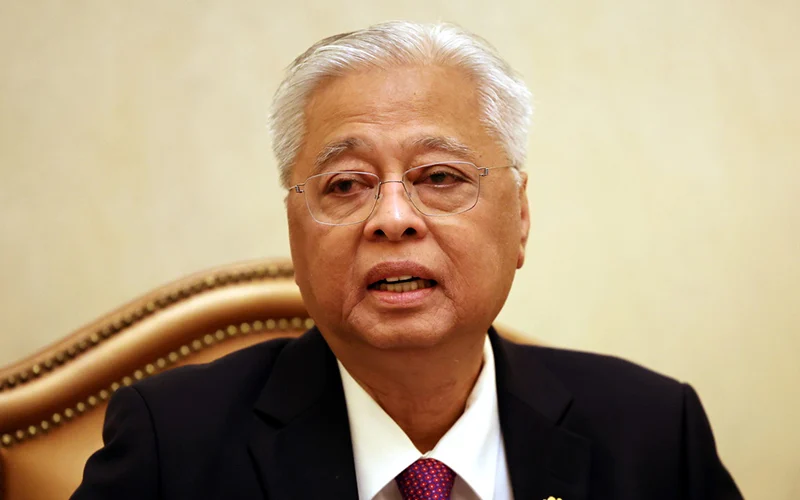

Elections could have been held at the latest by September 2023, but caretaker Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob had been under intense pressure from his United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) to call an early vote to capitalise on recent state election victories by the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition and get ahead of economic headwinds that are expected to worsen next year.

With the Parliament now dissolved, the election must be held within 60 days, but the approaching monsoon season will compress the time frame, ensuring UMNO has the inside running against a disunited opposition and even its erstwhile allies. Its clear aim is to win big in its own right, having dispensed with recent coalition partners the Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS) and Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) led by former prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin.

That Sabri was pressured into calling an election speaks to the enduring power of the UMNO old guard. Despite being Prime Minister, as junior party Vice-President Sabri is lower in the UMNO hierarchy than Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, UMNO President, and by extension, former Prime Minister Najib Razak. With Zahid and Najib facing corruption trials, the elevation of Sabri to the prime ministership last year was the price UMNO was willing to pay to form a new coalition to replace the previous alignment headed by Muhyiddin Yassin, which was another unelected government built upon the implosion of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government elected in 2018.

Arguably the only useful outcome of the 22-month Pakatan Harapan coalition headed by Mahathir Mohamed, along with perennial bridesmaid Anwar Ibrahim, until February 2020, were the court proceedings instituted against Najib and Zahid.

Najib was found guilty by the High Court in July 2020 on all charges of abuse of power, criminal breach of trust, and money laundering, but was allowed to remain free and politically active for more than two years until his legal appeals were finally exhausted in August, whereupon he began a 12-year jail term. He still faces four other trials.

Zahid is also battling graft charges, although he got a reprieve when he was acquitted in September in one of two cases. In the second case, he faces 47 criminal charges related to the alleged misappropriation of US$11.42 million from his family-owned foundation set up to help the economically disadvantaged.

Despite the stench of corruption, the UMNO old guard retains the loyalty of the party rank-and-file. The UMNO’s patronage culture, deeply embedded over several decades, rewards such loyalty over merit – a core national handicap. Yet, this very culture has helped UMNO sweep a string of state and national by-elections over the past three years, entrenching an expectation that the next election will usher in some kind of restoration of “normality”. This could include judicial reversals in the aforementioned corruption cases, although UMNO leaders do not declare such wishes – history suggests they do not need to.

While UMNO is divided into Zahid-Najib and Sabri factions, it faces a demoralised opposition still smarting from the ignominy of losing government less than two years after its historic election win. Their prime ministerial candidate is Anwar Ibrahim, but this time without the support of Mahathir, whose refusal to honour his agreement to hand over the prime ministership led to the collapse of their government.

Mahathir has announced that his Gerakan Tanah Air (GTA) coalition of small Malay-Muslim parties has decided that he should recontest the seat he won in 2018. The 97-year-old former prime minister also stated that he would consider working with Bersatu, which he founded and led before being sacked, as well as Anwar’s Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR). “The problem is that he (Anwar) doesn’t want to work with me. I am a very nice man,” he said, drawing laughter from the media.

Mahathir’s grouping will contest in Malay-dominated parliamentary seats, although analysts say Mahathir’s pull may no longer hold ethnic Malay voters who supported him in 2018.

Meanwhile, Anwar appears a spent force, with his Pakatan Harapan coalition beset by infighting, intra-party rivalries and low member participation in recent elections. The original PH manifesto had pledged to undo the counterproductive excesses of the Malay agenda that Mahathir himself had inaugurated, winning overwhelming non-Malay support in 2018 for equitable governance based on need, not race. But that vision alarmed heartland Malays, who felt sidelined by a government that no longer privileged their needs and sensibilities.

The coming election may well default in favour of UMNO, but with the judicial process for its leadership yet to fully play out, the lowering of the voting age from 21 to 18, and a new law preventing members from switching parties once elected, the outcome is far from certain.

Tags: Malaysia