Australia/Israel Review

DECONSTRUCTION ZONE: Middle East Ostriches

Apr 1, 2005 | Ted Lapkin

Middle East Ostriches

During the 1950s, Stanford psychologist Leon Festinger studied a small religious cult that was preaching a doctrine of impending global apocalypse. The appointed hour of doom came and went, and the rhythms of normal life continued without pause.

But the failure of the predicted cataclysm to materialise had the opposite effect of what might logically be assumed. Rather than sow the seeds of doubt, this frustrated prophecy actually served to reinforce the belief of cult members. Festinger coined the term “cognitive dissonance” to describe this phenomenon when objective fact butts heads with theology and comes out the loser.

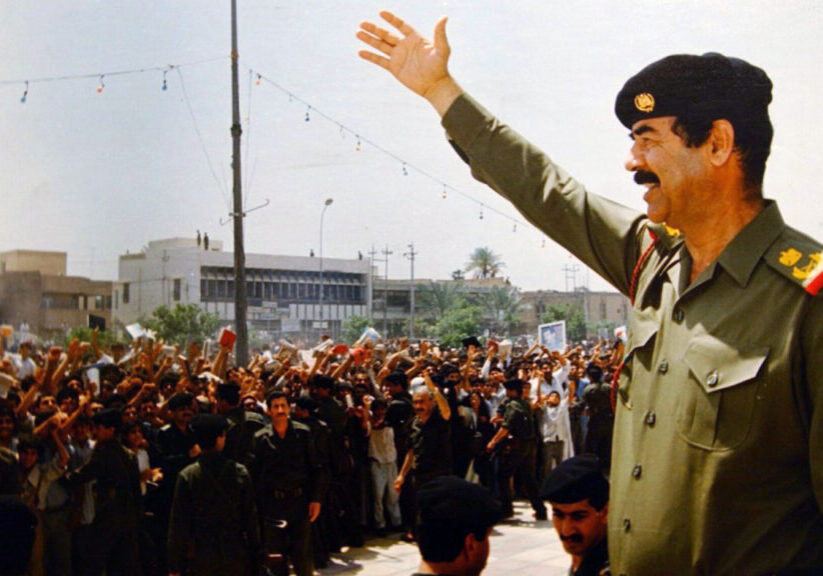

And what is true for apocalyptic cults in the 50s could equally be applied to those for whom the evil of the war in Iraq is an article of votive faith. To the true believers of the anti-war Left, the entire enterprise of the American-led coalition is tainted by original sin. The idea that anything positive might result from the overthrow of Saddam Hussein is treated with all the tolerance of medieval attitudes towards heresy.

But we have recently seen the spectacle of one million Lebanese flooding the streets of Beirut to demand an end to Syria’s occupation and a beginning of true democracy. Only a little less high profile is the news that Egypt’s autocratic regime will permit political opposition movements to run in the upcoming presidential ballot. Massive protests have broken out in Iran, with demonstrators reportedly cursing the ruling Islamic mullahs and demanding a referendum on democratic rule. And even in that most die hard bastion of dour Wahhabism, Saudi Arabia, authorities countenanced the free elections at the level of local government.

Is it mere happenstance that all this is occurring in the wake of the elections in Iraq: the first truly free ballot organised and conducted by Arabs in any Arab country? That is an increasingly hard line of argument to maintain.

All of which constitutes a serious psychological challenge to those who are emotionally wedded to the ‘Yankee go home’ view of the world. The waxing tide of liberty that is coursing through the Middle East has not yet reached the proportions of a tsunami that will sweep everything before it. But while this wave is in many ways incipient, it is still far too substantial to be ignored. That is, unless you have a doctrinal axe to grind and a doctrinaire agenda to defend.

The human capacity for self-delusion is boundless, and even when the facts are stacked against you the outright denial of reality always remains a viable option. Miranda Devine’s column in the Sun Herald (Mar. 20) provided signal service by illustrating the more acute form of this syndrome in two notable members of the commentariat. The ABC’s Monica Attard took the more conventional track, simply gainsaying that any credit belonged to the much despised United States. “Not by any stretch of the imagination” could the pro-democracy demonstrations in Beirut be linked to the fall of Ba’athist Baghdad, Attard declared.

But then The Guardian’s Timothy Garton Ash proceeded to stretch the imagination to the ludicrous and beyond by arguing that true acclaim for the march of liberty through Lebanon rightly belongs to: Osama bin Laden. In the eyes of Garton Ash, the bill indictment against American policy remains untarnished by current events. The ‘Cedar Revolution’ in Beirut “does not mean that George Bush was right all along.” To a writer of his impeccable leftist credentials, the dispensation of the slightest encomium to a Republican American president would be unthinkable. If Garton Ash did so he would be doubtless hounded out of the guild in the manner of Christopher Hitchens.

Of course not all versions of this media myopia manifest themselves in quite so burlesque a form. For some in the punditocracy, the task of allocating praise to the Bush administration is merely the equivalent of pulling teeth rather than amputating a limb. A series of recent columns by the Lowy Institute’s Anthony Bubalo exemplify the offerings at the slightly less cataract-afflicted end of the spectrum. And I do mean spectrum, because Bubalo’s views appear in several different iterations.

The most uncompromising of Anthony Bubalo’s pieces appeared in the mid-March edition of the Australian Jewish News. There he contended that we have “good reasons to be sceptical” of any claim that the tremors of democracy that have shaken the Arab world have any relation to American policy. It could not be denied, said Bubalo, that the US had “thrown a giant stone into a politically-stagnant Middle East pond.” But the signs of freedom’s flowering in the Levant were taking place, not because, but in spite of the “ham fisted diplomacy” and “messianic fervour” of George W. Bush.

But the version of Bubalo’s article that ran the next day in the Sydney Morning Herald steered a slightly more nuanced tack. It was now “niggardly — if not foolish — to claim that the Iraq war has not shaken the region from its politically stagnant state.” The only motivation for Egypt’s first tentative moves toward openness that Anthony Bubalo saw fit to cite in his AJN column was pressure from the grassroots anti-American ‘Kiffaya’ movement. Yet in his SMH piece Bubalo credited American diplomatic pressure as well.

On ABC Radio National’s ‘Perspective’ op-ed program, Bubalo had moved a bit further in the direction of reality, conceding that “Washington’s elevation of democratisation” had “catalysed indigenous forces for change.” And by the time he appeared on the ABC’s “The World Today”, he had ratcheted his rhetoric a few more notches yet again: “there can be no doubt that the Iraq War, the Iraq elections” and the “democratisation in the Bush administrations’ rhetoric is having a major impact on the region.”

Full circle? Well, not exactly, because if there was a consistent theme to the Bubalo medley it was that giving credit to George Bush and his policies was a useless distraction.

But the apportionment of political acclamation is important; and not merely for the anointment of inflated human egos. By exalting a particular policy we endorse it. And the more widely endorsed the policy of promoting liberty becomes, the more credibility it accrues. With greater grassroots currency the principle of actively promoting freedom will proliferate more rapidly and more broadly.

Yet in the name of foreign policy realism, Anthony Bubalo demeans the essential nobility of this Anglo-American-Australian endeavour to disseminate political self-determination to the Arab world. By so doing he plays the role of spoiler and obstructionist to a process that is both politically expedient and morally incumbent.

TED LAPKIN

Tags: Iraq