Australia/Israel Review

The Terror Triangle

Oct 27, 2009 | Frederick Kagan & Kimberley Kagan

By Frederick Kagan & Kimberley Kagan

US President Barack Obama has announced his intention to conduct a review of US strategy in Afghanistan from first principles before deciding whether or not to accept General Stanley McChrystal’s proposed strategy and request for more forces. This review is delaying the decision. If the delay goes on much longer, it will force military leaders either to rush the deployment in a way that increases the strain on soldiers and their families or to lose the opportunity to affect the spring campaign. The president’s determination to make sure of his policy before committing the additional 40,000 or so forces required by Gen. McChrystal’s campaign plan is, nevertheless, understandable. The conflict in Afghanistan is complex, and it is important that we understand what we are trying to do.

Al-Qaeda and the Taliban

At the centre of the complexity is a deceptively simple question: If the United States is fighting a terrorist organisation – al-Qaeda – why must we conduct a counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan against two other groups – the Quetta Shura Taliban and the Haqqani Network – that have neither the objective nor the capability to attack the United States or Western targets outside Afghanistan? Shouldn’t we fight a terrorist organisation with a counterterrorist strategy, customarily defined as relying on long-range precision weapons and Special Forces raids to eliminate key terrorist leaders? Why must we become embroiled in the politics and social dysfunctionality of the fifth-poorest country in the world?

This argument rests on two essential assumptions: that al-Qaeda is primarily a terrorist group and that it is separable from the insurgent groups among whom it lives and through whom it operates. Let us examine these assumptions.

Al-Qaeda is a highly ideological organisation that openly states its aims and general methods. It seeks to replace existing governments in the Muslim world, which it regards as apostate, with a regime based on its own interpretation of the Koran and Muslim tradition. The question of the religious legality of killing Muslims causes tensions within al-Qaeda and between al-Qaeda and other Muslims, leading to debates over the wisdom of fighting the “near enemy,” i.e., the “apostate” Muslim governments in the region, or the “far enemy”, i.e., the West and especially the United States, which al-Qaeda believes provides indispensable support to these “apostate” governments. The 9/11 attack resulted from the temporary triumph of the “far enemy” school.

Above all, al-Qaeda does not see itself as a terrorist organisation. It defines itself as the vanguard in the Leninist sense: a revolutionary movement whose aim is to take power throughout the Muslim world. It is an insurgent organisation with global aims. Its use of terrorism (for which it has developed lengthy and abstruse religious justifications) is simply a reflection of its current situation. If al-Qaeda had the ability to conduct guerrilla warfare with success, it would do so. If it could wage conventional war, it would probably prefer to do so. It has already made clear that it desires to wage chemical, biological, and nuclear war when possible.

For al-Qaeda, terrorism is a start, not an end, nor even the preferred means. It goes without saying that the United States and the West would face catastrophic consequences if al-Qaeda ever managed to obtain the ability to wage war by different means.

Al-Qaeda does not exist in a vacuum like the SPECTRE of James Bond movies. It has always operated in close coordination with allies. The anti-Soviet jihad of the 1980s was the crucible in which al-Qaeda leaders first bonded with the partners who would shelter them in Afghanistan. Osama bin Laden met Jalaluddin Haqqani, whose network is now fighting US forces in eastern Afghanistan, as both were raising support in Saudi Arabia for the mujahedeen in the 1980s. They then fought the Soviets together. When the Soviet Army withdrew in 1989 (for which bin Laden subsequently took unearned credit), Haqqani seized the Afghan city of Khost and established his control of the surrounding provinces of Khost, Paktia, and Paktika. Haqqani also retained the base in Pakistan – near Miranshah in North Waziristan – from which he had fought the Soviets. He established a madrassa there that has become infamous for its indoctrination of young men in the tenets of militant Islamism.

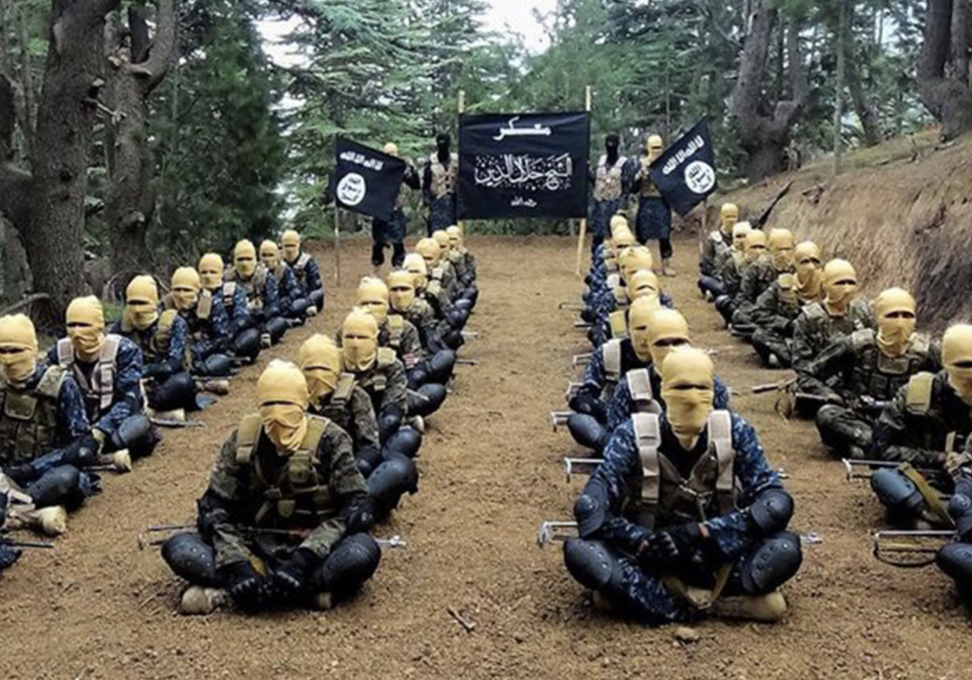

Haqqani held onto Greater Paktia, as the three provinces are often called, and invited bin Laden to establish bases there in the 1990s in which to train his own cadres. When the Taliban took shape under Mullah Muhammad Omar in the mid-1990s (with a large amount of Pakistani assistance), Haqqani made common cause with that group, which shared his ideological and religious outlook and seemed likely to take control of Afghanistan. He became a minister in the Taliban government, which welcomed and facilitated the continued presence of bin Laden and his training camps.

Bin Laden and al-Qaeda could not have functioned as they did in the 1990s without the active support of Mullah Omar and Haqqani. The Taliban and Haqqani fighters protected bin Laden, fed him and his troops, facilitated the movement of al-Qaeda leaders and fighters, and generated recruits. They also provided a socio-religious human network that strengthened the personal resilience and organisational reach of bin Laden and his team. Bin Laden’s Taliban allies provided the intellectual and social support network al-Qaeda needed to keep fighting. In return, bin Laden shared his wealth with the Taliban and later sent his fighters into battle to defend the Taliban regime against the US-aided Northern Alliance attack after 9/11.

The relationship that developed between bin Laden and Mullah Omar was deep and strong. It helps explain why Mullah Omar refused categorically to expel bin Laden after 9/11 even though he knew that failing to do so could lead to the destruction of the Taliban state – as it did. In return, bin Laden recognises Mullah Omar as Amir al-Momineen – the “Commander of the Faithful” – a religious title the Taliban uses to legitimise its activities and shadow state. The alliance between al-Qaeda and the Haqqanis (now led by Sirajuddin, successor to his aging and ailing father, Jalaluddin) also remains strong. The Haqqani network still claims the terrain of Greater Paktia, can project attacks into Kabul, and seems to facilitate the kinds of spectacular attacks in Afghanistan that are the hallmark of al-Qaeda training and technical expertise. There is no reason whatever to believe that Mullah Omar or the Haqqanis – whose religious and political views remain closely aligned with al-Qaeda’s – would fail to offer renewed hospitality to their friend and ally of 20 years, bin Laden.

Mullah Omar and the Haqqanis are not the ones hosting al-Qaeda today, however, since the presence of US and NATO forces in Afghanistan has made that country too dangerous for bin Laden and his lieutenants. They now reside for the most part on the other side of the Durand Line delineating the Afghan-Pakistan border, among the melange of anti-government insurgent and terrorist groups that live in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan. These groups – they include the Tehrik-e Taliban-e Pakistan, led until his recent death-by-Predator by Baitullah Mehsud; the Tehrik-e Nafaz-e Shariat-e Mohammadi; and the Lashkar-e-Taiba, responsible for the Mumbai attack – now provide some of the same services to al-Qaeda that the Taliban provided when they ruled Afghanistan. Mullah Omar continues to help, moreover, by intervening in disputes among the more fractious Pakistani groups to try to maintain cohesion within the movement. All of these groups coordinate their activities, moreover, and all have voices within the Peshawar Shura (council). They are not isolated groups, but rather a network-of-networks.

All of which is to say that the common image of al-Qaeda leaders flitting like bats from cave to cave in the badlands of Pakistan is inaccurate. Al-Qaeda leaders do flit – but they flit like guests from friend to friend in areas controlled by their allies. Their allies provide them with shelter and food, with warning of impending attacks, with the means to move rapidly. Their allies provide communications services – runners and the use of their own more modern systems to help al-Qaeda’s senior leaders avoid creating electronic footprints that our forces could use to track and target them. Their allies provide means of moving money and other strategic resources around, as well as the means of imparting critical knowledge (like expertise in explosives) to cadres. Their allies provide media support, helping to get the al-Qaeda message out and then serving as an echo chamber to magnify it via their own media resources.

The theory proposed by some in the White House and the press that an out-of-country, high-tech counterterrorist campaign could destroy a terrorist network such as al-Qaeda is fraught with erroneous assumptions. Killing skilled terrorists is very hard to do. The best – and most dangerous – of them avoid using cellphones, computers, and other devices that leave obvious electronic footprints. Tracking them requires either capitalising on their mistakes in using such devices or generating human intelligence about their whereabouts from sources on the ground. When the terrorists operate among relatively friendly populations, gaining useful human intelligence can be extremely difficult if not impossible.

Counterterrorist forces do best when the terrorists must operate among neutral or hostile populations while under severe military pressure, including from troops on the ground. Such pressure forces terrorist leaders to rely more on communications equipment for self-defence and for coordination of larger efforts. It greatly restricts the terrorists’ ability to move around, making them easier targets, and to receive and distribute money, weapons, and recruits. This is the scenario that developed in Iraq during and after the surge.

The most serious operational challenge of the pure counterterrorist approach, however, is to eliminate bad guys faster than they can be replaced. Isolated killings of senior leaders, spread out over months or years, rarely do serious systemic harm to their organisations.

One essential question that advocates of a pure counterterrorism approach must answer, therefore, is: Can the United States significantly accelerate the rate at which our forces identify, target, and kill senior and mid-level leaders? Our efforts to do so have failed to date, despite the commitment of enormous resources to that problem over eight years at the expense of other challenges. Perhaps there is a way to increase the attrition rate. If so, advocates of this approach have an obligation to explain what it is. They must also explain why removing US and NATO forces from the theatre will not make collecting timely intelligence even harder.

Pursuing a counterinsurgency strategy against the Taliban and Haqqani groups – that is, using American forces to protect the population from them while building the capability of the Afghan Army – appears at first an indirect approach to defeating al-Qaeda. In principle, neither the Taliban nor the Haqqani network poses an immediate danger to the United States. Why then should we fight them?

We should fight them because in practice they are integrally connected with al-Qaeda. Allowing the Taliban and the Haqqani network to expand their areas of control and influence would offer new opportunities to al-Qaeda that its leaders appear determined to seize. It would relieve the pressure on al-Qaeda, giving its operatives more scope to protect themselves while working to project power and influence around the world. It would reduce the amount of usable intelligence we could expect to receive, thus reducing the rate at which we could target key leaders.

Pakistan and the War in Afghanistan

Meanwhile, the “fundamental connection” between Afghanistan and Pakistan was one of the important principles President Obama laid out in his March 27, 2009, speech announcing his policy in South Asia. It reflected a common criticism of the Bush policy in Afghanistan, which was often castigated as insufficiently “regional.” It also reflected reality: The war against al-Qaeda and its affiliates is a two-front conflict that must be fought on both sides of the Durand Line.

Now, however, some of the most vocal supporters of the regional approach are considering – or even advocating – a return to its antithesis, a purely counterterrorism (CT) strategy in Afghanistan.

Recent discussions of the “CT option” have tended to be sterile, clinical, and removed from the complexity of the region – the opposite of the coherence with which the administration had previously sought to address the problem. In reality, any “CT option” will likely have to be executed against the backdrop of state collapse and civil war in Afghanistan, spiralling extremism and loss of will in Pakistan, and floods of refugees.

Within Pakistan, the US reversion to a counterterrorism strategy (from the counterinsurgency strategy for which Obama reaffirmed his support as recently as August) would disrupt the delicate balance that has made possible recent Pakistani progress against internal foes and al-Qaeda.

Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari, army chief of staff General Ashfaq Kayani, and others who have supported Pakistani operations against the Taliban are facing an entrenched resistance within the military and among retired officers. This resistance stems from the decades-long relationships nurtured between the Taliban and Pakistan, which started during the war to expel the Soviet Army. Advocates within Pakistan of continuing to support the Taliban argue that the United States will abandon Afghanistan as it did in 1989, creating chaos that only the Taliban will be able to fill in a manner that suits Pakistan.

Zardari and Kayani have been able to overcome this internal resistance sufficiently to mount major operations against Pakistani Taliban groups, in part because the rhetoric and actions of the Obama Administration to date have seemed to prove the Taliban advocates wrong. The announcement of the withdrawal of US combat forces would prove them right. Pakistani operations against their own insurgents – as well as against al-Qaeda, which lives among those insurgents – would probably grind to a halt as Pakistan worked to reposition itself in support of a revived Taliban government in Afghanistan. And a renewed stream of Afghan refugees would likely overwhelm the Pakistani government and military, rendering coherent operations against insurgents and terrorists difficult or impossible.

The collapse of Pakistan, or even the revival of an aggressive and successful Islamist movement there, would be a calamity for the region and for the United States. It would significantly increase the risk that al-Qaeda might obtain nuclear weapons from Pakistan’s stockpile, as well as the risk that an Indo-Pakistani war might break out involving the use of nuclear weapons.

The “Status Quo” Option

What if the United States did not withdraw the forces now in Afghanistan, but simply kept them at current levels while emphasising both counterterrorism and the rapid expansion of the Afghan security forces? Within Afghanistan, the situation would continue to deteriorate. Neither the United States and NATO, nor Afghan forces, are now capable of defeating the Taliban in the south or east. At best, the recently arrived US reinforcements in the south might be able to turn steady defeat into stalemate, but even that is unlikely.

The accelerated expansion of Afghan security forces, moreover, will be seriously hindered if we fail to deploy additional combat forces. As we discovered in Iraq, the fastest way to help indigenous forces grow in numbers and competence is to partner US and allied units with them side by side in combat. Trainers and mentors are helpful – but their utility is multiplied many times when indigenous soldiers and officers have the opportunity to see what right looks like rather than simply being told about it. At the current troop levels, commanders have had to disperse Afghan and allied forces widely in an effort simply to cover important ground, without regard for partnering.

As a result, it is very likely that the insurgency will grow in size and strength in 2010 faster than Afghan security forces can be developed without the addition of significant numbers of American combat troops.

The Obama Administration is not making this decision in a vacuum. Obama ran on a platform that made giving Afghanistan the resources it needed an overriding American priority. President Obama has repeated that commitment many times. He appointed a new commander to execute the policy he enunciated in his March 27 speech, in which he noted: “To focus on the greatest threat to our people, America must no longer deny resources to Afghanistan because of the war in Iraq.” If he now rejects the request of his new commander for forces, his decision will be seen as the abandonment of the president’s own commitment to the conflict.

In that case, no amount of rhetorical flourish is likely to persuade Afghans, Pakistanis, or anyone else otherwise. And if the United States is not determined to succeed, then, in the language of the region, it is getting ready to cut and run, whatever the president and his advisers may think or say.

That is a policy that will indeed have regional effects – extremely dangerous ones.

Frederick W. Kagan is a military historian and resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Kimberly Kagan is president of the Institute for the Study of War and the author of The Surge: A Military History. © Weekly Standard, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Afghanistan/ Pakistan