Australia/Israel Review

The Muslim Brotherhood’s Radical Plan for Egypt

Jan 25, 2012 | Eric Trager

Eric Trager

When the third and final round of Egypt’s parliamentary elections concluded on January 11, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) cemented its dominance of the next legislature. Although the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces still holds executive power, the FJP’s political victory promises radical changes for Egypt, including a theocratic domestic program and a confrontational foreign policy. Western states should have no illusions about the party’s aims or ability to moderate.

The FJP was licensed on April 30, 2011, making it the second new party to be recognised by the Egyptian government following Hosni Mubarak’s February 11 ouster. Initially, it sought to assuage fears of a post-Mubarak Islamist takeover by promising to run for fewer than 50% of the seats. But after its electoral alliance with the Wafd Party broke down in late October, the FJP announced that it would contest 77% of the seats.

In the first round of the elections, which began on November 28, the FJP’s coalition won an estimated 73 of 150 seats (48.7%), and in the second round, which began on December 14, an estimated 79 of 172 seats (45.9%). Following the third round, which took place in early January and included traditional Brotherhood strongholds such as the Gharbiyah and Daqahliyah governorates, the FJP ended up with 47% of all seats.

A Theocratic Domestic Policy

The FJP’s overriding aim is to establish an Islamic state in which Sharia would be the primary source of legislation. Although FJP leaders correctly note that “Sharia principles were a main source of legislation” under Article II of the 1971 constitution, which was suspended following Mubarak’s ouster, the party intends to implement Sharia-based laws far more comprehensively than was previously done. The FJP platform states that “Sharia, in its essence…organises the various aspects of life for Muslims and those non-Muslims who participate in the state with them.” The party’s theocratic aims are therefore likely to change many aspects of Egypt’s domestic policy.

First, FJP leaders have repeatedly said that they would ban alcohol and beach bathing – both of which are essential to a tourism industry that accounts for roughly 10% of the economy. Second, Egypt faces a severe cash crisis, and its ability to attract international investment may be hampered by the Brotherhood’s intention to implement the Koranic prohibition on interest-based banking. Third, newly elected FJP parliamentarians have said that they will not tolerate criticisms of Islam or Sharia, including those made by Christians and secularists. In recent months, Brotherhood-affiliated lawyers have filed suits against organisations and individuals accused of insulting Islam. These attempts to limit free speech are likely to intensify once the FJP assumes control of parliament.

A Confrontational Foreign Policy

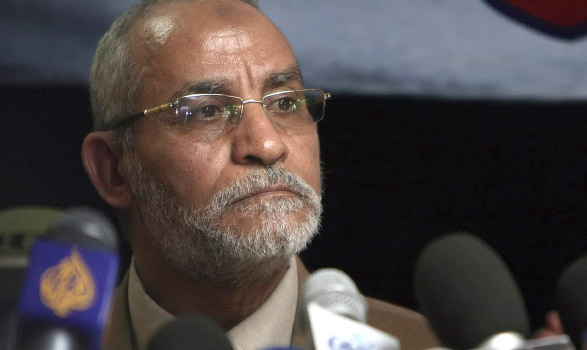

The Brotherhood is similarly signalling its preference for radicalism over realism in foreign affairs. For example, Supreme Guide Muhammad Badie recently declared that, after forming the new government, the organisation would pursue its final goal of establishing a “rightly guided caliphate for the education of the world.” This goal may be unrealistic in the short term, but the Brotherhood is already working through the FJP to tilt Egypt away from its Western allies and toward an Islamist foreign policy.

The peace treaty with Israel will likely be the first casualty of an FJP-led government. Although the party has said that it will honour Egypt’s international agreements, it has carved out an exception for the Camp David Accords, which it intends to put to a national referendum, thereby shielding itself from direct responsibility for the treaty’s demise. Meanwhile, the Brotherhood has amplified its confrontational posture toward Israel in recent weeks by vowing never to recognise the state and warmly greeting Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Cairo.

Not Likely to Moderate

It is tempting to believe that the FJP will moderate once in power, but four factors make this highly unlikely. First, although the Brotherhood has frequently portrayed the FJP as a separate entity, the distinction between the “organisation” and its “political wing” is superficial. The Brotherhood’s fifteen-member Guidance Office elected the FJP’s leaders, all of whom are former members of that office. Moreover, the choice of hardliner Muhammad Morsi as the FJP’s first chairman suggested that the Brotherhood was committed to ensuring the party would not veer from its parent organisation’s principles.

Second, the Brotherhood ensures the FJP’s ideological rigidity by retaining direct control over its parliamentary nomination process. The new FJP parliamentarians are all longtime Muslim Brothers whose candidacies were thoroughly vetted by multiple layers of the organisation’s leadership.

Third, the emergence of the Salafist al-Nour party as Egypt’s second-strongest faction makes moderation a strategically dangerous choice for the FJP. Much of al-Nour’s appeal is based on its claim to represent the “true” Islam, making it a respected arbiter of Islamic principles within Egyptian politics. The FJP thus risks losing support among an overwhelmingly religious electorate if it is perceived to be veering from its Islamist doctrine.

Finally, the FJP has invited al-Gamaa al-Islamiyah, a US-designated terrorist organisation, to join its future governing coalition. The inclusion of this radical, historically violent faction further reduces the likelihood of the Brotherhood pursuing a moderate agenda.

Policy Options

The fact that the FJP has won parliamentary power via elections should not fool policymakers into believing that the organisation is committed to democratic principles or moderation. For this reason, Washington should use its current engagement with Brotherhood leaders to communicate that the future of their relations with Egypt depends on the organisation’s behaviour regarding key Western interests.

Given the Brotherhood’s anti-Western outlook, however, Western governments must prepare for the strong possibility that it will hold only limited influence with Egypt’s next government.

Eric Trager, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s Ira Weiner fellow, is a doctoral candidate in political science at the University of Pennsylvania, where he is writing his dissertation on Egyptian opposition parties. © Washington Institute, reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Egypt